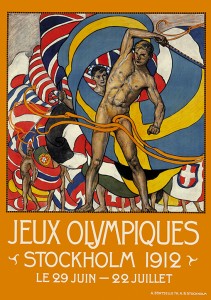

The National Heritage Centre for Horseracing and Sporting Art – to give it its full title – was formally opened on 3rd November 2016 by Her Majesty the Queen, a lifelong devotee and patron of the turf. It is the outcome of a lengthy, highly ambitious campaign to establish a centre for the rehabilitation of racing and sporting art in general as an important strand in British culture, social history and art. British horseracing and its sporting art tradition had a major impact on advanced French painting in the nineteenth century – Géricault, Manet and Degas all painted horseracing scenes. It became an archetypal modern subject, dramatic, contemporary and non-Classsical, and the image of a galloping horse continued into the twentieth century as a metaphor for speed of change and technical progress.

Located on a five-acre site at the heart of Newmarket, the capital of horseracing, the National Heritage Centre comprises three separate sections: The Fred Packard Museum and Galleries of British Sporting Art, The National Horseracing Museum and a museum of the living horse. These combine to present a comprehensive picture of the history, art and science of the sport from its early royal and aristocratic beginnings to its evolution as a global industry, the sixth largest in the UK. As the National Heritage Centre is very much about breaking down barriers between the racing world and a wider public, the horse should be put before the art and the last section, which presents the opportunity to experience living racehorses at close hand, visited first. Racehorses can be seen being shod, exercised on the ‘Horse Walker’ and being retrained on retirement for careers outside racing. The Rothschild Yard is the flagship home of the Retraining of Racehorses charity. In addition, there are regular parades of former champion racehorses and a changing programme of equine events in the arena.

The National Horseracing Museum traces the evolution and science of the Thoroughbred racehorse, along with the history of horseracing in Britain from Tudor times to the present day, through a series of informative wall texts, paintings, documents, photographs, audio visual screens and interactive displays. The Thoroughbred racehorse, we discover, is a supreme equine athlete, which only evolved as a specific breed between 1680 and 1740 by crossing imported pure-bred Arabian stallions with home-bred mares. Thanks to DNA the three foundation stallions, the Darley Arabian, the Byerley Turk and the Godolphin Arabian are now joined by a fourth, the Curwen Bay Arabian or Barb. 95% of the current Thoroughbreds go back through the male line to the Darley Arabian – a form of Orientalism in reverse. It is fascinating to find out what makes the English Thoroughbred racehorse the ultimate equine speed machine.

The Anatomy of the Horse

by George Stubbs (1724–1806), 1766 (first edition)

For George Stubbs, who did more than any other eighteenth-century artist to establish a new anatomy of the horse based on scientific dissection, the answer lay in the mechanics of the horse’s construction. In a quite remarkable series of anatomical drawings of dissections carried out between 1756 and 1757 he laid bare the mechanics of the horse, muscle by muscle, tendon by tendon to reveal the ‘chassis’, the skeleton. Worked up into the 18 plates of his famous book The Anatomy of the Horse, finally published in 1766, a copy of which is on exhibition in Palace House, he completely redefined what a horse should look like. Stubbs’s omission of the Thoroughbred racehorse’s unique cardio vascular system is rectified in a remarkable audio-visual display, Inside the Racing Machine. Before seeing it I had no idea that to increase the delivery of oxygen to the muscles the spleen contracts with each stride to release an extra 12 litres of blood into circulation, almost doubling its oxygen capacity, and that a Thoroughbred racehorse’s heart is almost double the size of a normal horse’s.

The Racing Machine in the Maktoum Gallery of the Thoroughbred

The import of Arabian and Barb stallions to improve home-bred stock was not a novelty in Europe. A charming, slightly naïve provincial painting in The National Horseracing Museum by an unknown artist depicts Sir John Cotton Showing His Mantuan Horses to Charles II at Newmarket (c.1670).

Sir John Cotton Showing His Mantuan Horses to Charles II at Newmarket

by unknown artist, c.1670

The Gonzaga family in Renaissance Italy, who started off as condottiere, mercenary leaders, then hereditary rulers of Mantua, a small mosquito ridden city state at the mouth of the Po, went on to achieve a status in Europe way beyond their military prowess through their horses. The Gonzagas' success can be put down to their breeding policy.

Lodovico II, second Marquis of Mantua (r. 1444–1478), had the foresight to set up a series of studs to breed specialised horses, often cross breeding with imported North African and Middle Eastern stock: corsieri, compact, obedient and ideally suited to tournaments; ginetes, noble Spanish horses with North African Barb blood, the preferred mounts for riding, and most prestigious of all barbari, their racehorses, which were either barbari naturali, pure bred Barbs from North Africa, or barbari de la casa, home cross-breds between pure Barbs and Irish hobbies. In addition, speedy turchi, Turkumans, were imported from the Ottoman Empire.

Compact and elegant, almost pony-like, with a remarkable turn of speed Gonzaga horses made most contemporary horses look slow, cumbersome, shaggy and old fashioned. European monarchs, including Henry VIII, competed for them. Gonzaga running horses raced in England during the reign of James I who was the first monarch to use Newmarket as a base for hunting, hawking and racing.

The Round Course at Newmarket, Cambridgeshire, Preparing for the King's Plate

c.1725

Peter Tillemans (1684–1734)

Charles II revived the family interest and did more than any other British monarch to put horseracing and Newmarket on the map. From his return to the town in 1666 to his last visit in 1684, the year before his death, he constructed the new Palace to replace the Royal Palace destroyed during the Commonwealth, set up the Round Course and won what is traditionally considered the first Town Plate. It is therefore fitting that the final part of the National Heritage Centre, The Fred Packard Museum and Galleries of British Sporting Art is located in part of his former palace.

The Fred Packard Museum and Galleries of British Sporting Art is to be seen as a national gallery of sporting art. In addition to the paintings collected by the British Sporting Art Trust, the inaugural hang contains generous loans from the Tate Gallery, Victoria & Albert Museum, Manchester City Art Gallery, The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, Sir Alfred Munnings Museum and Art Gallery and other national institutions and private collections. Apart from horses and horseracing the collection includes hunting, ferreting, fishing, shooting, falconry, coursing, archery, croquet, golf, prize fighting, cricket, rugby and finally, football. Palace House is the successful outcome of a lengthy campaign by the British Sporting Art Trust which was formed in 1979 to combat the prejudice against sporting art and the seepage of so many outstanding sporting paintings to collections abroad. The national collections had largely ignored sporting art which was regarded as a minor genre, a lowbrow activity, and not taken seriously.

Young True Blue at Newmarket

1717

John Wootton (c.1682–1764)

The collection in Palace House is hung chronologically. A distinct national school of British sporting art only evolved in the eighteenth century. The forgotten father of the genre was John Wootton (1682–1764). Prior to Wootton sporting art was largely the province of Flemish and Dutch specialist genre painters, like his teacher Jan Wyck (1684–1734). Wootton developed an elevated style and vocabulary to suit his new equine aristocratic subjects. Standing thoroughbreds with graceful swan necks, small heads and long tapering legs are held by grooms and silhouetted from a low view-point against a racecourse or classical architecture. Racehorses in training and racing became spectacles to be commemorated. Wootton included himself in the foreground recording George I watching horses in training on the slopes of Warren Hill during his only visit to the town in October 1717. George Stubbs (1724–1806) invested Wootton’s subject matter with a new monumentality and realism, based on scientific observation, which transcended the boundaries of the genre. Fighting Stallions interlock in an arch of ferocity, a sublime subject symbolic of the awe-inspiring destructive power of nature.

Field sports became extremely fashionable in the nineteenth century. Foxhunting, before the growth of football, was the national sport and the main horseraces mass spectator events. Field sports were something to be seen doing, even if you were not particularly keen on them. John Singer Sargent portrays Lady Fishing – Mrs Ormond 1889 holding the oars like accessories in a fashion shoot.

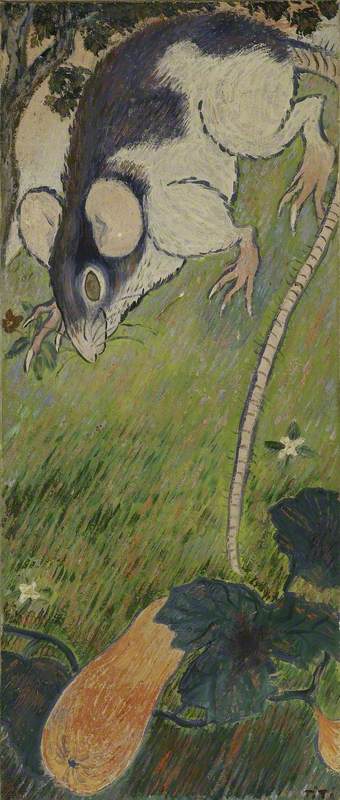

Modern artists were often drawn to more robust, behind the fashionable scenes subjects. Robert Bevan (1865–1925), a founder member of the Camden Town Group of British realists, who had worked with Gauguin at Pont Aven in Brittany, painted Horse Dealers (Sale at Ward’s Repository No.1) in typically bold patterned shapes and bright colours.

Horse Dealers (Sale at Ward's Repository No. 1)

1918

Robert Polhill Bevan (1865–1925)

Alfred Munnings, though initially drawn to landscapes, atmospheric provincial hunting scenes in Cornwall and picturesque gypsy horse subjects, ended up as the most fashionable horse painter of the twentieth century and the self-avowed defender of tradition against modern art. The Start shows Munnings at his best brilliantly evoking the tension and movement of the runners jockeying for position. However, Munnings’s attack on modern art at his farewell banquet as President of the Royal Academy in 1949 not only damned him in the eyes of the new art establishment but also made sporting art in general a toxic subject. This has now changed.

Moving up for the Start: Under Starter's Orders, Newmarket

Alfred James Munnings (1878–1959)

A generation of young British artists who came to the fore in the 1990s made class and prejudice their subject matter. The Turner Prize winner Mark Wallinger (born 1959), a racehorse owner and devotee of the turf made his reputation on the back of a horse. Wanting, he said, ‘an art that connected with the world and with a public beyond a small esoteric coterie’, he exhibited in 1994 his own racehorse registered under the name A Real Work of Art as a work of art in its own right. His statuette of the subject concludes the final gallery. Racehorses have long been a paradoxical symbol of both tradition and social change. Wallinger’s purple, white and green racing colours are in homage to the colours of the suffragette movement and Emily Davison who was crushed to death attempting to pin a suffragette sash to the bridle of King George V’s horse Anmer in the Derby of 1913. With a rolling programme of changing exhibitions in The Temporary Exhibition Galleries it is hoped that The National Heritage Centre for Horseracing & Sporting Art will encourage the study and enjoyment of a neglected topic.

Dr Nicholas Watkins, art historian