Eva Lutyens was a successful fashion designer of the 1930s. Clients included fabulously wealthy society hostesses and the most notorious woman of the day: Wallis Simpson. For her first and highly controversial meeting with her lover’s parents, the King and Queen, Wallis chose to wear a dazzling purple lamé dress with an emerald sash created by Eva Lutyens.

Born Eva Lubrynska or Lubrynsky in Russia around 1894, Eva pursued an early career in science, studying chemistry in Paris with Marie Curie and publishing several research articles on biochemistry. Her uncle was Chaim Weizmann, an internationally renowned research chemist and Zionist campaigner who became the first President of Israel.

One lover was the Russian novelist Vladimir Nabokov. Their relationship almost culminated in engagement but he found her 'demanding and unsure of what she demanded, unhappy, always torturing herself'. In 1920, Nabokov introduced Eva to Robert Lutyens, the son of architect Sir Edward Lutyens. Possibly to Nabokov’s relief, the two started a relationship immediately and were soon married. Robert was a talented interior designer and together they were celebrated as one of the most stylish couples in London.

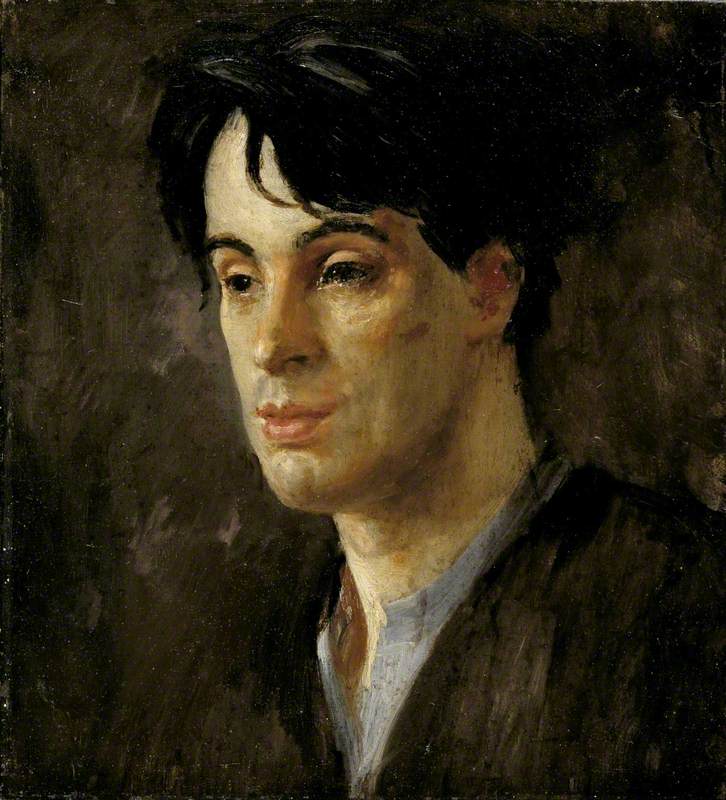

Eva began her couturier business sometime in the early 1930s and by 1934 her designs were appearing in international fashion magazines. It was at this stage of her life that Eva had her portrait painted.

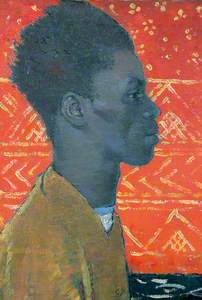

The artist, Glyn Warren Philpot, studied at Lambeth School of Art and at the Académie Julian in Paris. His charming personality and deft, polished style brought him success as one of the leading portrait painters of the day.

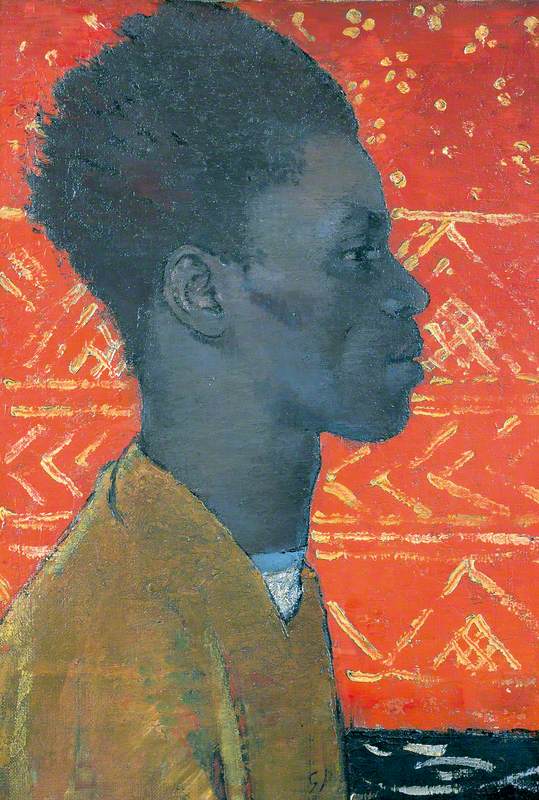

He was elected to the Royal Academy in 1923. Philpot was openly homosexual and a favourite model was his handsome, black studio assistant, Henry Thomas, who was believed to be his lover.

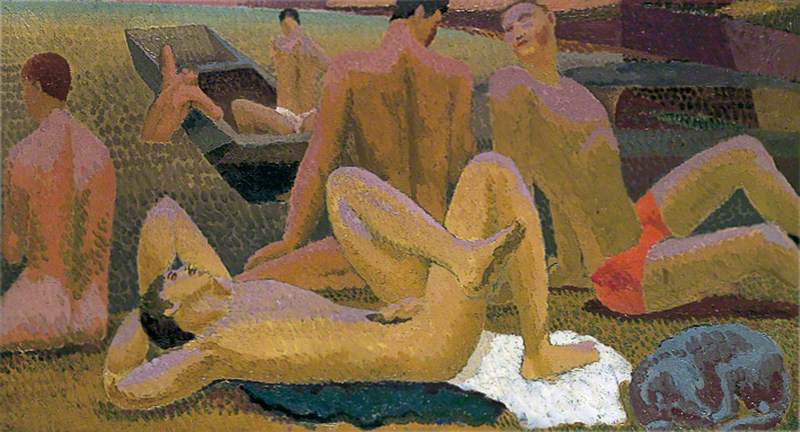

In 1931, Philpot tired of the type of work he was doing and spent time in Berlin, immersing himself in the decadent underworld of the Weimar Republic. Artistically, he became influenced by Oskar Schlemmer, a designer and choreographer at the Bauhaus school who focused on the juxtaposition of figures and the space around them. German Expressionist artists, especially Otto Dix, were another evident inspiration.

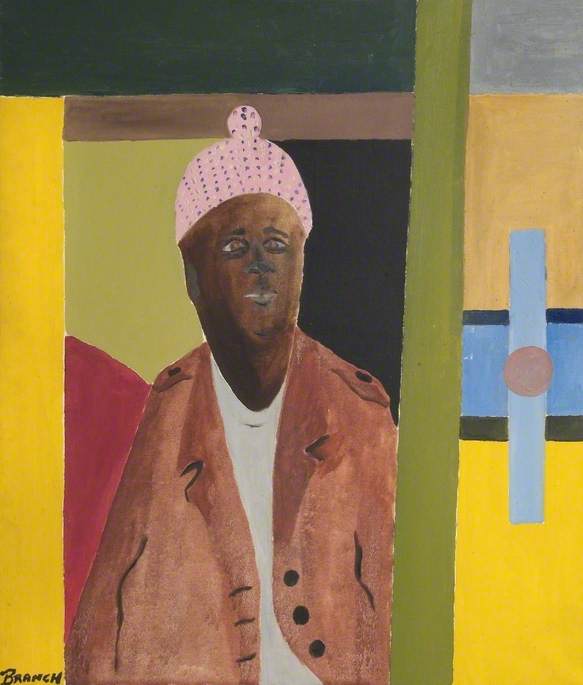

Philpot returned to London in 1932 with a brand-new artistic style and a portfolio of new work to exhibit. Unfortunately, it was not universally liked: 'Glyn Philpot Goes Picasso' reported The Scotsman. Eventually, commissions began to roll in for his new portrait style, which used a dabbing brushstroke thick with paint to give a fractured effect with deep impasto.

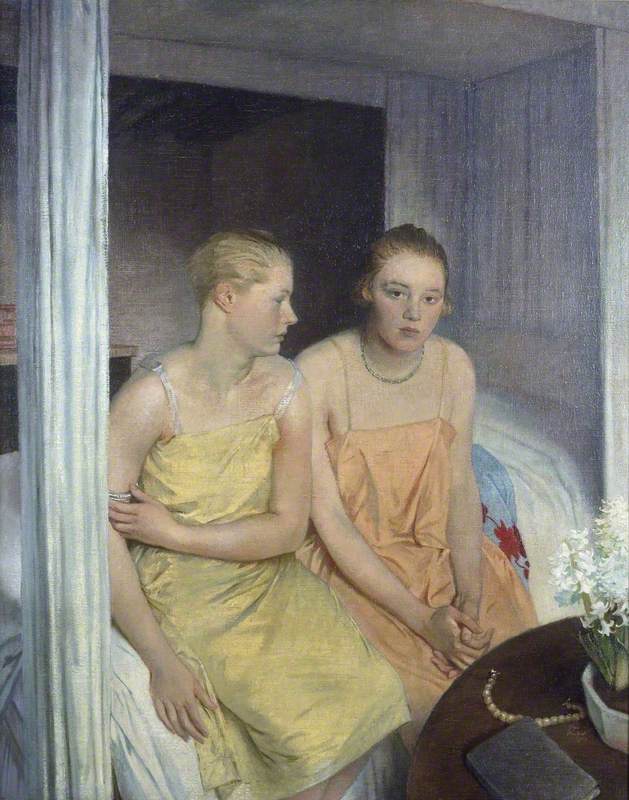

The Marchioness of Carisbrooke (1890–1956)

1925

Glyn Warren Philpot (1884–1937)

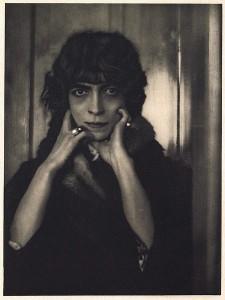

Of all these later works, the portrait of Eva is probably the most confident and successful. Her glamorous and dramatic looks stimulated Philpot’s interest and he was obviously intrigued by her persona: highly intelligent and creative but darkly troubled in unfathomable ways. Philpot draws attention to Eva’s hands making the fingers exaggeratedly long to emphasise how she uses them for her work. The twin jewelled cuffs were made of semi-precious stones and obviously important to Eva; she is seen wearing them in a 1938 photograph and bequeathed them to her sister-in-law in her will. The portrait dates from about 1935 and is certainly no later than 1937 because, at the end of that year, Philpot suddenly collapsed and died in his studio of a heart attack. He was 53.

And what happened to Eva? There was no place for the excesses of haute couture during the austerity of war and her company ceased trading. By the time the economy was getting back on its feet in 1950, the Lutyens’ marriage was in trouble. Robert left Eva for a much younger woman and the two divorced after 31 years together. Eva remained alone. Their only child, David, was a published writer but a troubled soul who spent periods in psychiatric institutions. Even David’s close friend described him as 'the most spectacular misfit of his generation'.

Eva died in 1963. In her will she bequeathed her portrait to the Tate in London but with the imperious conditions that they hang it permanently on the ground floor and absolutely not in the basement. If the Tate officials would not agree to this (and they didn’t) the painting was to be given to a provincial art gallery. There is no obvious reason why the trustees of her will approached The Atkinson because, as far as we know, neither Eva nor Philpot had any connection to Southport. Today, Eva’s portrait is displayed regularly and visitors to The Atkinson find it fascinating but rather perplexing. She remains enigmatic to the last.

Dr Amanda Draper, freelance curator and Art Detective Group Leader: North West and Cumbria