Science fiction writing and a type of visual artistry go hand in hand, as anyone who has ever marvelled at the production design of the rain-soaked Los Angeles in Bladerunner or taken an interest in H. R. Giger through his iconic Alien will know.

The art and design creates the world that supports the fantastical story, whether it's a painstakingly detailed set, groundbreaking special effects or just the pulp aesthetic of science fiction comics.

However, finding science fiction among the nation's oil paintings is not that easy. The world of fine art doesn't often cross into the realm of science fiction. Many paintings have their fantastical elements – particularly once you delve into Surrealism – but the aesthetics of science fiction are not tackled in fine art as they are in comics, books and film.

But while it may be a challenge, the connections are there: tiny overlaps in the Venn diagram of 'the nation's oil paintings' and 'science fiction'. So far as we can tell, no one else has really tried to trace this path yet. So, let's boldly go into the nation's art collection in search of science fiction.

The worlds of Ray Harryhausen

First up is a bona fide science fiction hero. Ray Harryhausen's world-building work in film and TV made him beloved of the generation who grew up on his creations, inspiring Steven Spielberg, James Cameron and Peter Jackson. He laid the foundations for science fiction on screen; George Lucas claimed that there would have been no Star Wars without Harryhausen’s influence. While he worked across the board on visual effects, writing and producing, Harryhausen is best remembered for his iconic stop-motion movie monsters, created with a pioneering technique he called 'dynamation'. His New York Times obituary puts it rather beautifully: 'Ray Harryhausen, the animator and special-effects wizard... found ways to breathe cinematic life into the gargantuan, the mythical and the extinct.'.

Allosaurus Attacking a Cowboy

1938/1939

Ray Harryhausen (1920–2013)

Art UK features works from the Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation, set up to archive and preserve Harryhausen’s collection of some 50,000 items, and to promote the art of stop-motion animation. Some of the paintings point directly to Harryhausen’s films, such as the above meeting of a dinosaur and cowboy, created in 1938/1939. In 1969, Harryhausen worked on his last dinosaur film, The Valley of Gwangi, where cowboys do battle with a variety of stop-motion dinosaurs – including the Allosaurus.

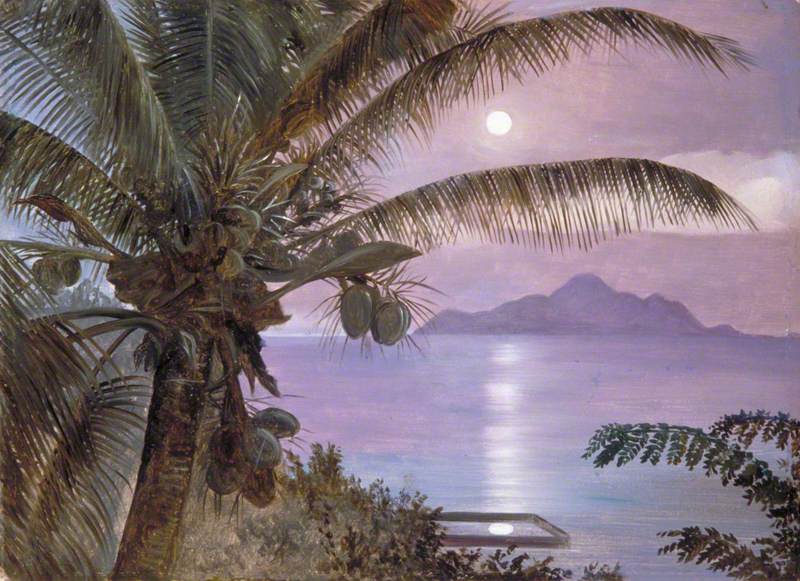

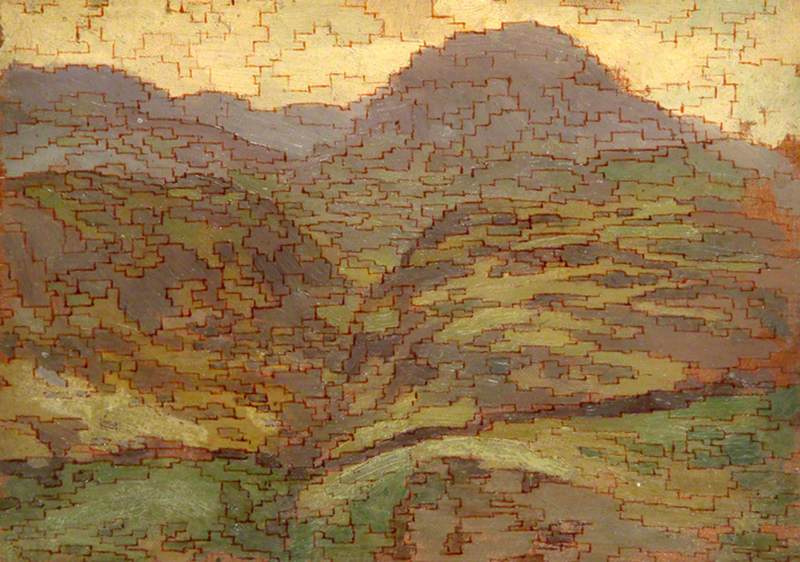

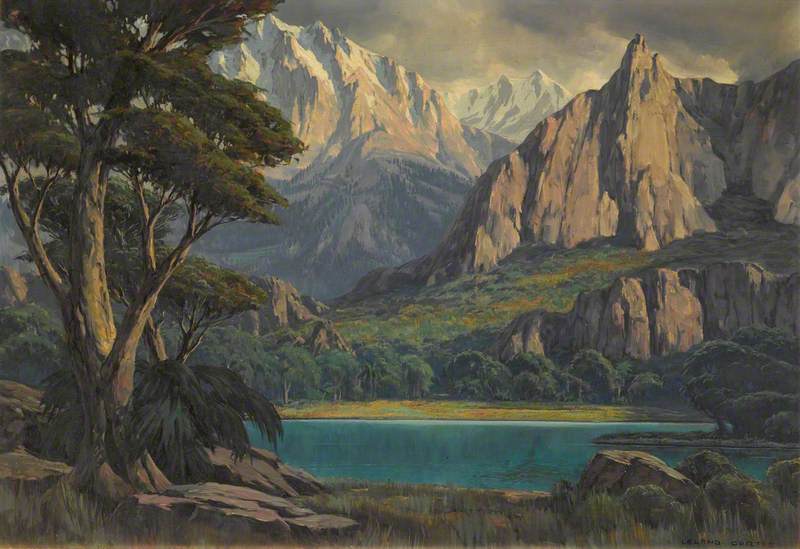

The other paintings in the Harryhausen collection reveal some possible inspirations for the artist himself. There's the luminous, fantastical scale of Joseph Michael Gandy's Jupiter Pluvius, and Leland Curtis' Lake by Mountain Range, originally painted for a film, and which could almost be a scene from Conan Doyle's The Lost World – itself an inspiration for the numerous dinosaur films Harryhausen helped to create.

Lake by Mountain Range (War Eagles)

c.1939

Leland Curtis (1897–1989)

Surrealism meets science fiction

J. G. Ballard's most famous works may not be immediately reminiscent of science fiction – Crash, known mainly for its controversy, certainly doesn't fit the usual picture of the genre, if you're thinking silver spaceships and aliens. Perhaps this is why he himself used the term 'apocalyptic' to describe his dystopian visions. However, his science fiction credentials are all there, particulaly in his early novels, when he successively imagines future worlds ravaged by wind, by water, by heat; human civilisations just about clinging on.

Ballard was an author heavily inspired by the visual arts, as he detailed in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist:

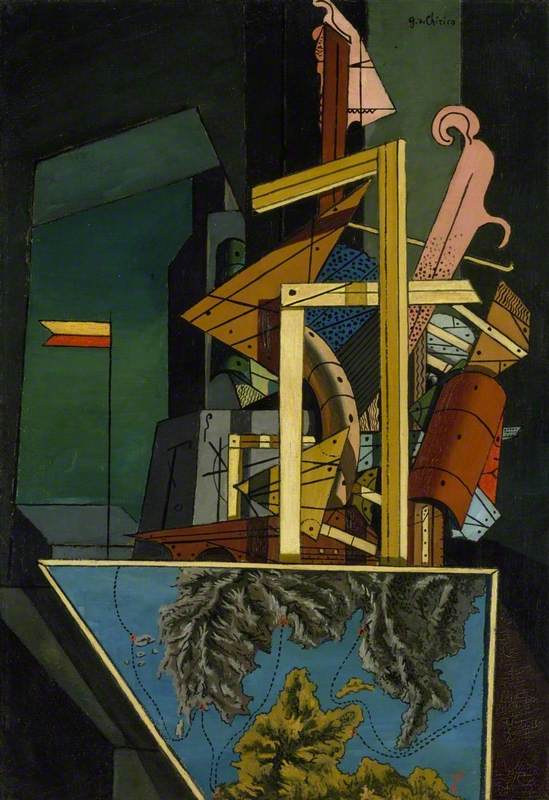

'...I think the surrealist painters had the biggest influence on me – de Chirico, Ernst, Dali and Delvaux. These are all painters of mysterious and disconnected landscapes, through which the few human beings drift in a state of dream-like trance, which had a direct and powerful appeal for me.'

On reading a Ballard novel, the parallels with Surrealism are quickly spotted: he envisages worlds that are often dreamlike, and often horrifying, plunging the reader into a place somewhere between the real world and that of the subconscious. There are also parallels with Pop Art, both casting a sideways eye over modern life, suspicious of its effects, seeking to expose its fakery.

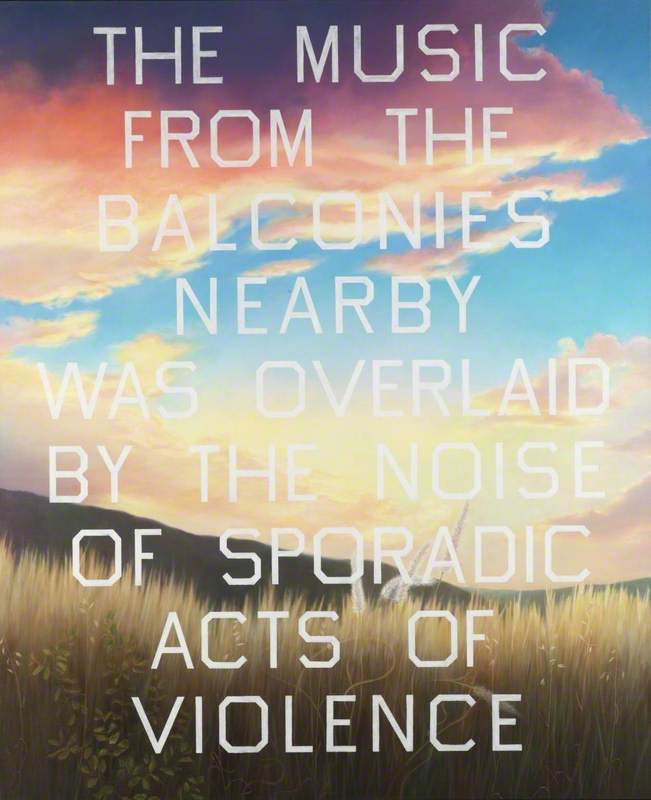

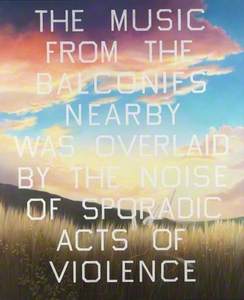

The art world embraced Ballard too. The year after his death, an exhibition at the Gagosian featured works by artists 'tuned to the Ballardian universe', including Ed Ruscha, Richard Hamilton (both friends of Ballard's), Andy Warhol, Tacita Dean and Jenny Saville. Ruscha's painting below takes a line from High Rise and places it over a pastoral, peaceful background: in much the same way that Ballard uses shocking phrases in a matter-of-fact way in the novel – including the famous opening line: 'As he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months.'.

Gulliver’s Travels: the original science fiction?

Gulliver’s Travels is, first and foremost, satire. But it's argued that, if not the first work of science fiction (an honour often given to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein or The Last Man), it is at least proto-science fiction. The elements are all there: the journey of our ‘normal’ protagonist to far off, strange lands, where he encounters otherworldly species; the encountering of seemingly utopian and dystopian societies, which have hidden depths beyond their surface.

Gulliver Exhibited to the Brobdingnag Farmer

(from Jonathan Swift's 'Gulliver's Travels') 1836

Richard Redgrave (1804–1888)

Some of the most striking visual imagery called to mind by the book is from parts one and two. Gulliver visits the land of tiny Lilliputians, where he is comparably a giant, and the land of giants, where he becomes a miniature curiosity. Yet in the third section of the novel, Gulliver is saved from being marooned by the people of Laputa, a floating island controlled by the metal it sits on, and where the people are driven by their dedication to science alone. The paintings that bring to life Gulliver's Travels on Art UK sadly don't include an imagining of Laputa, but there is a depiction of the Houyhnhnms, a race of talking horses.

Laputa’s civilisation was Swift’s satire on the Royal Society, and a warning about the dangers of pursuing science and reason above all else, allowing morals, art and ethics to fall by the wayside. The idea of the floating island, particularly one controlled by metal and magnetism, is amazingly far-sighted for an author writing in the eighteenth century. Swift's visionary imagination of future technologies, and the idea that we might become so preoccupied with what we can do that we forget exactly why we’re doing it, seems classic science fiction territory. Let's not forget about the arts when our robot overlords come.

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer