We all die three times: the first time is when your heart stops beating, you stop breathing, and you are pronounced medically dead. The second time is when your family marks your passing with a funeral or ceremony and says their last goodbyes to your material remains. And your final death occurs the very last time anyone ever speaks your name in this world. I heard this said several years ago on the radio one evening as I was driving home; I almost had to pull over and have never forgotten it. Of course, this is why we all long for some form of immortality – a reminder that our life has mattered beyond our short years alive, and past the lives of our family and friends who knew us.

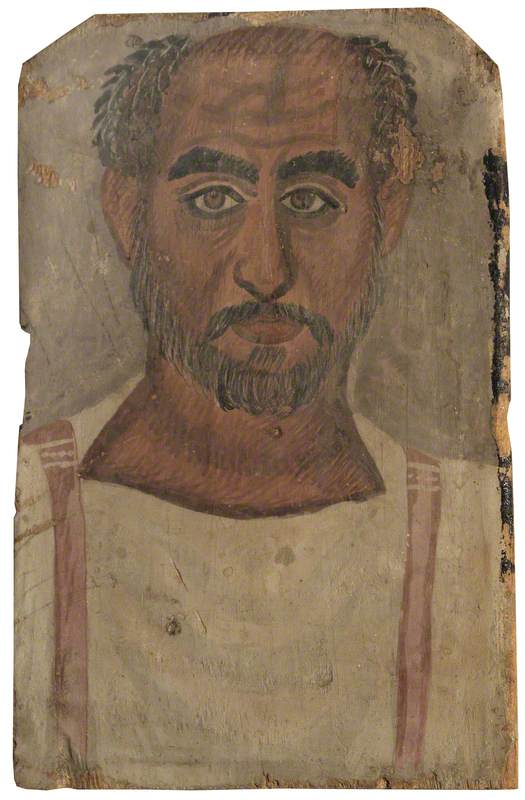

Perhaps this is why I find Fayum mummy portraits so very compelling. They seem timelessly contemporary and simultaneously anachronistic. We see a real person staring out at us, making direct eye contact and challenging us to engage with them. And they each ask us to remember them for the individuals that they once were. They offer us a rational descriptiveness along with the highly irrational desire to live forever.

These death portraits, painted on board and nearly life-sized, were attached to the deceased’s mummy linen cocoon in the location where the face would have been. The effect is as though the deceased stares at us through a window or a kind of otherworldly portal, looking simultaneously alien and of this world. It is the portrait’s connection to life and to death that gives them much of their power. The liminal quality of mummy portraits such as this one is likely part of what drew Sigmund Freud to them.

Made during Roman-era Egypt, these portraits were found in a cemetery in the Fayum Oasis, on the left bank of the Nile. Since not everyone could afford the expense of mummification and portrait painting, we assume that our gentleman was of an upper class. He has bushy dark eyebrows and a neatly trimmed beard and mustache. His head is balding and his forehead creased; he looks like someone we might have seen on the bus this afternoon. The artist’s efforts at individualization make us wonder about the deceased; what was his profession? Of what did he die? Did he have a family? Was he kind? Did he make his friends laugh?

In his work, the Houston-based artist Dario Robleto frequently poses questions which ask us whether love, compassion, care, and empathy can reach across time and space. Scientists who work in the area of empathy often emphasize that we need to get proximate to other people in order to empathize with them. Can we, therefore, really empathize with an anonymous man who lived in Egypt and died almost 2,000 years ago? Absent detailed information about who he was as a person, does his face, painted in encaustic on board and staring out at us, make us care for him or develop a connection with him? This is indeed the power of art; it is an expression of the human lived experience that speaks to us across continents and across the centuries.

We are not lucky enough to have a Fayum mummy portrait in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art but I would be most grateful to have this one. If this unnamed gentleman were to hang on the wall of our museum, I would visit him regularly and reflect on his time on earth and his significance in our world today.

Kaywin Feldman,