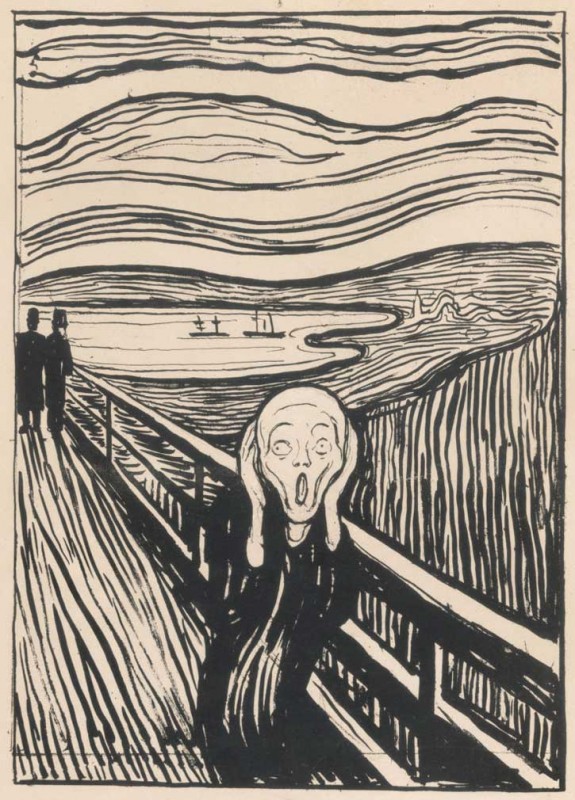

In 1868, art critic Philip Gilbert Hamerton wrote about the 'contempt' many contemporary artists were starting to feel with regard to 'literary interest, dramatic interest, historical interest and all other such extraneous interests', adding that the 'especial merchandise' of painting consisted of 'visible melodies and harmonies – a kind of visible music – meaning as much and narrating as much as the music which is heard in the ears, and nothing whatever more.'

It was true. Nineteenth-century painters, anxious to free their art from the shackles of narrative, looked to music as an art form that could produce an impact on the listener without needing images or stories or any kind of representation. So did theorists, critics and other writers on art. Reviewing an exhibition in London that included works by the Russian Wassily Kandinsky, Roger Fry turned to precisely the same analogy when he declared that, on closer inspection, Kandinsky's paintings became 'more definite, more logical and more closely knit in structure, more surprisingly beautiful in their colour oppositions, more exact in their equilibrium. They are pure visual music.'

In fact, Fry was not only describing Kandinsky's paintings – he was also echoing the Russian artist's concerns. In his book On the Spiritual in Art, published a year earlier, Kandinsky had written:

'An artist who sees that the imitation of natural appearances, no matter how artistic, is not for him – the kind of creative artist who wants to, and has to, express his own inner world – sees with envy how naturally and easily such goals can be attained in music, the least material of the arts today.'

Composition IV, 1911 #kandinsky #vasilykandinsky pic.twitter.com/3RXhe3CmwQ

— Wassily Kandinsky (@artistkandinsky) February 15, 2022

Around that time, Kandinsky started giving musical titles to his paintings, calling them 'Improvisations', 'Compositions' – even, on one later occasion, 'Fugue'. Of these, his Composition IV of 1911 is especially significant, being one of the very few works he ever described or analysed in detail. Interestingly, he identified a number of objects within what might otherwise be mistaken for an 'abstract' picture – a battle, a castle on a hill, lances. These same motifs are also visible in a smaller painting, called Cossacks, which reproduces in an almost literal fashion the left-hand part of the larger composition.

But he also writes at some length about the purely emotive effects of the colours and forms he uses, describing the lines that create movement as 'angular' and 'sharp', the colours as 'light', 'cold' and 'sweet'. Regardless of the presence – or absence – of objects, Kandinsky clearly expected those 'abstract' elements of the picture to affect his audience directly, just like the tones of music.

Not only the colours and forms but also the motifs themselves may likewise have a 'musical' significance. Clearly visible in the smaller, truncated version of the composition is the outline of the castle on a hill, which Kandinsky himself identifies, and a rainbow, which he does not mention.

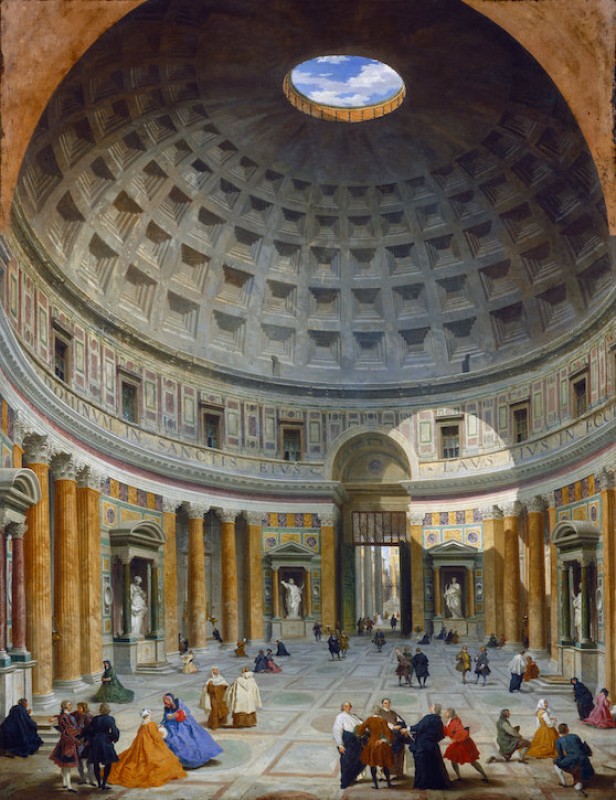

To opera lovers, these two motifs in juxtaposition will inevitably call to mind the closing pages of Wagner's music drama Das Rheingold, the first part of his epic Ring cycle. The castle is surely Valhalla, which Wotan, the father of the gods, and his companions will enter by crossing the rainbow bridge that spans the River Rhine. Meanwhile, in the waters beneath, the Rhinemaidens bewail the loss of their magic gold, stolen from them and used to pay for this, Wotan's long-dreamt-of (and newly completed) building project.

Nowhere does Kandinsky refer specifically to this scene from Rheingold; but he did know a good deal about Wagner. In his 1912 essay 'On Stage Composition', he discusses the composer's operas in some detail, including the famous musical device of the Leitmotif. And in his autobiographical Reminiscences, published a year later, he describes a formative experience he underwent as a young man: seeing Wagner's Lohengrin at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. However, it was the music itself, rather than the drama or the staging, that had a profound effect on him:

'I saw all my colours in my mind, they stood before my eyes. Wild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me... It became quite clear to me that art in general was far more powerful than I had thought, and that painting could develop just such powers as music possesses.'

In Rheingold, the theft of the gold – which, when forged into a magic ring, will convey limitless power on its owner – is merely the prelude to a tragic chain of events which will ultimately bring about the downfall of the gods and the end of the old order – the 'twilight of the gods'. An apt metaphor, one might think, for the end of narrative painting and the advent of an entirely new, object-less form of visual art.

Peter Vergo, Emeritus Professor of Art History at the University of Essex