Defined by the gentle, rolling hills of the South Downs and the bright white chalk cliffs that abruptly punctuate the coast, Sussex has captured the imagination of artists and writers for generations. Since the nineteenth century, Sussex has been within easy travelling distance of London. Yet it provided a rural location where artists could work anonymously and escape the hustle and bustle of the city. Artists that travelled down to Sussex in the nineteenth century included J. M. W. Turner and John Constable but it was not until Britain found itself plunged into the first of two World Wars from 1914 that artists retreated to Sussex en masse.

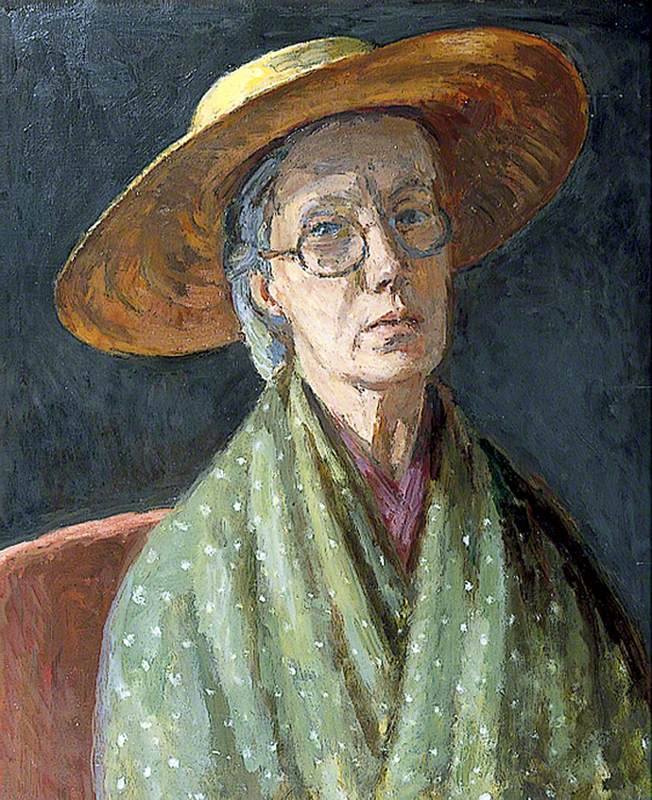

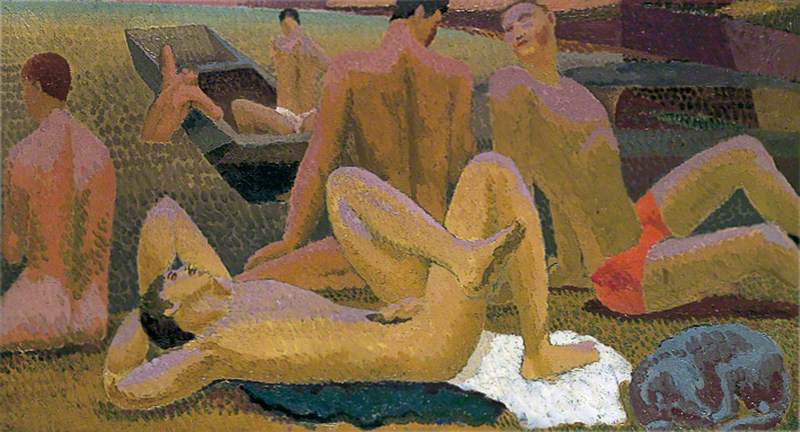

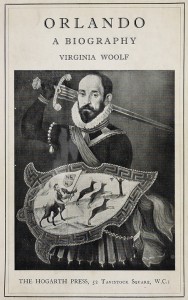

The most famous group of artists to escape London during the First World War was the Bloomsbury Group, a circle of artists, writers and intellectuals. Key members included the sisters Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf, Roger Fry and Duncan Grant. The Bloomsbury Group were politically and sexually liberal and their creative reputations are often entangled by a complicated web of relationships and affairs that took place between members.

By the summer of 1916, the First World War had already been raging for two years. A bill for conscription had been passed in March which meant that men between 18 and 41 could be called up for active service. The Bloomsbury Group were pacifists and conscientious objectors meaning they did not believe in war. In order for a healthy young man like Duncan Grant to be exempt from fighting he had to be undertaking important work at home. This brought Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and his lover David Garnett to Charleston, a dilapidated farmhouse nestled in the South Downs near the village of West Firle, East Sussex. It was here that Grant and Garnett were able to work on the agricultural land of the South Downs and meaningfully contribute to the war effort.

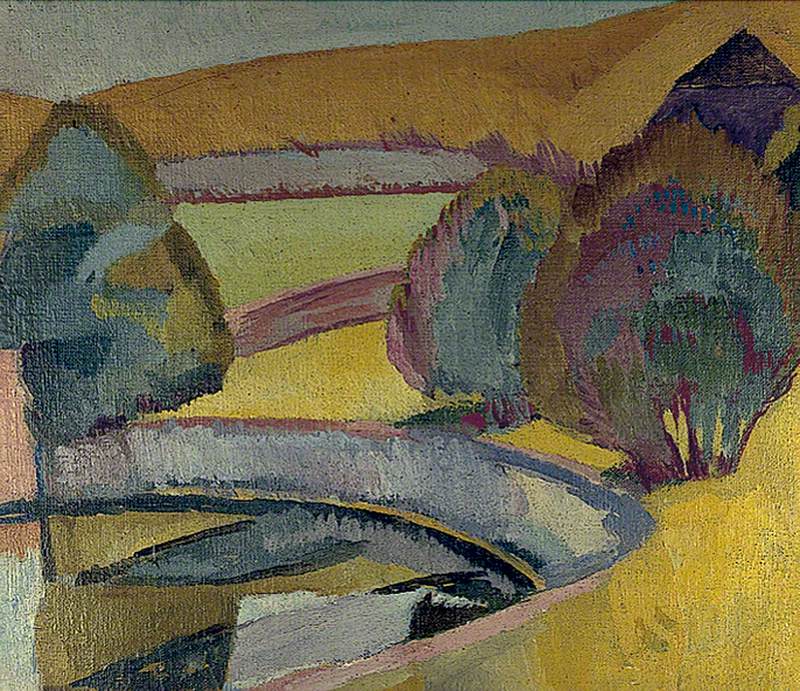

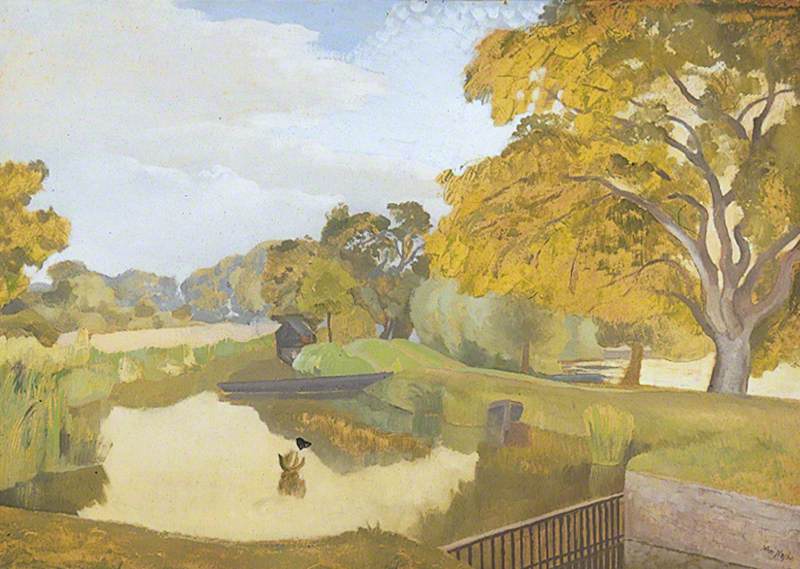

The Walled Garden, Charleston

1919–1920, oil on canvas by Roger Fry (1866–1934)

At the turn of the twentieth century, Charleston farmhouse had been used as a guesthouse but had fallen into disrepair. The house was cold all year round. It had no electricity, no telephone and no water heater, but Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell sought to make the house their own. They each chose studios in the house and decorated the interior with distinctive designs. They also painted the grounds and countryside surrounding the house a number of times. Paintings by Grant and Bell depicting the pond at Charleston farmhouse, as well as a painting by Roger Fry of the view of the Downs from an upstairs window, are currently on loan to Pallant House Gallery from Tate, Charleston and Philip Mould & Co., as part of the exhibition 'Sussex Landscape: Chalk, Wood and Water'.

Like the Bloomsbury Group, Frank Brangwyn also moved to Sussex from London to escape the First World War and became captivated by the surrounding landscape. Brangwyn and his wife Lucy moved to Ditchling in 1917 and bought a house steeped in history called The Jointure. The Jointure had been given to Anne of Cleves following her divorce from Henry VIII in 1540 and today is run as a bed and breakfast with self-contained studio flats.

The Brangwyns moved back to London after the First World War in 1920 but following Lucy's death just four years later, Frank Brangwyn returned to The Jointure and lived there for the rest of his life. It was after his return to Sussex that he painted From My Window at Ditchling.

In this painting, Brangwyn explores human interaction with the landscape as well as nature breaching the boundary between inside and outside. Green leaves from a climbing passion flower can be seen just beyond the windowsill outside. Inside, Brangwyn has chosen to display autumn leaves from an oak tree in a silver tankard. The gentle sunshine entering through the open window illuminates the leaves making them almost translucent. Painted in the months following his wife's death, Brangwyn has used the dead leaves, crockery and book to make a simple vanitas in the foreground of this composition – a work of art commenting on the fragility of life and the inevitability of human mortality.

The writer Eleanor Farjeon, like Brangwyn, relocated to Sussex to grieve following her friend's death in the First World War. Farjeon was close friends with the poet Edward Thomas and his wife Helen who lived just over the Sussex border in Steep, Hampshire. Thomas almost certainly introduced Farjeon to walking, an activity that would greatly inspire her writings as a successful author.

Devastated by Thomas' death, Farjeon rented The End Cottage on Mucky Lane (now South Lane), in Houghton, Amberley. She spent two years living alone at the property which became an important haven for her grief and for her writing. She was welcomed into the local community and would make friends during her rambles across the South Downs. Her walks would inspire stories, songs and poetry including All the Way to Alfriston, a poem which describes the villages and countryside that she saw on a 50-mile walk from Chichester.

After living in Mucky Lane for two years she returned to London where she had a successful career as a children's author. In 1924 she published A Sussex Alphabet as a series of poems for the West Sussex Gazette. Each letter of the alphabet was accompanied by a small verse or limerick about Sussex. These poems were later published as a limited-edition book in 1939. A copy of this rare book is owned by the South Downs National Park and is currently on view at Pallant House Gallery. Eleanor Farjeon returned to Sussex throughout her life and during the Second World War rented The Hammonds in Laughton near the Bloomsbury Group at West Firle.

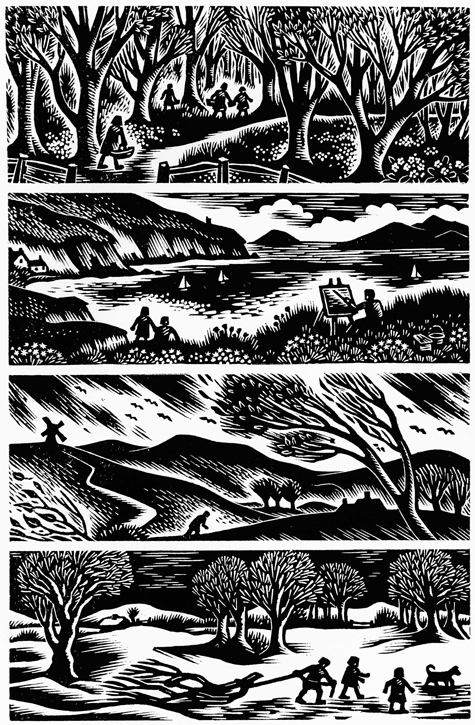

The number of artists and writers working in Sussex during the First World War, as well as the interwar period and the Second World War, is staggering. Official War Artists such as Paul Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson, Eric Ravilious and Graham Sutherland all painted and drew the Sussex landscape during this time. During the Second World War, the Sussex landscape was documented by the artist Charles Knight as part of the Recording Britain Project, and Gwenda Morgan – who is celebrated for her beautiful wood engravings of the county's countryside – worked for the Women's Land Army during the Second World War.

The Changing Year

1968, wood engraving on paper by Gwenda Morgan (1908–1991)

Sussex provided a rural retreat for these artists, a chance to escape the war or recover from its disastrous effects. Each of these artists defined Sussex in their own way during a period of intense national fear and their unique experiences of the landscape significantly contributed to their reputations as artists.

Dr Lydia Miller, Assistant Curator at Pallant House Gallery

'Sussex Landscape: Chalk, Wood and Water' runs at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester until 23rd April 2023