As 11th November 2018 marks the centenary of the Armistice we can take stock of the past four years of special commemorations of the First World War – remembrance of

The 14-18 NOW cultural programme, using government and lottery funding, has itself commissioned over 325 artworks and performances. These have linked to commemorative events led or coordinated by the Imperial War Museum, including those focused importantly on the contributions of black and Asian troops. These works of art have brought important shifts in perception, understanding

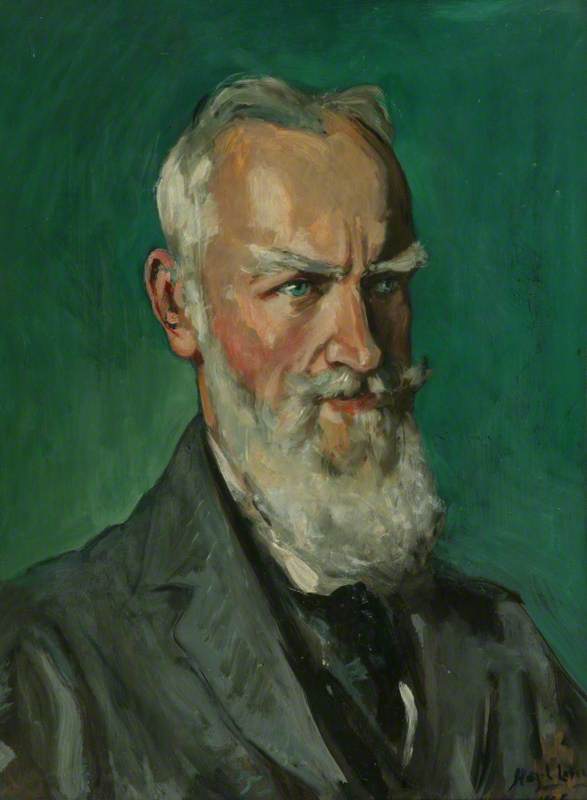

In the foreword to the National Portrait Gallery exhibition

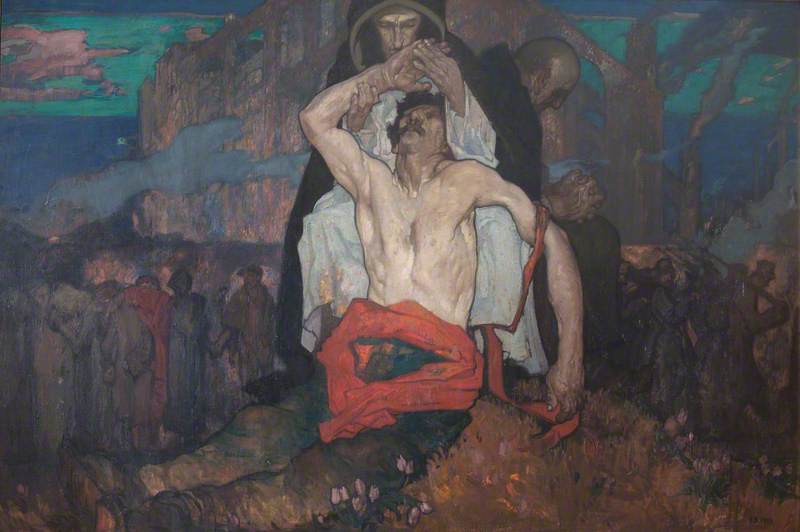

Paul Moorhouse curated this exhibition and explored the dissonance between official and sometimes ‘heroic’ portraits of senior officers (and winners of the Victoria Cross) and the depiction of individual soldiers, whether shown as courageous or pitiful. He included Eric Kennington’s 1918 painting, Gassed and Wounded, now in the Imperial War Museum. It is by no means a conventional portrait: faces of the key participants obscured by bandages or in deep shadow. Writing in 1934 Kennington described

The humanity of this painting mixes with its sheer despair. It asks how

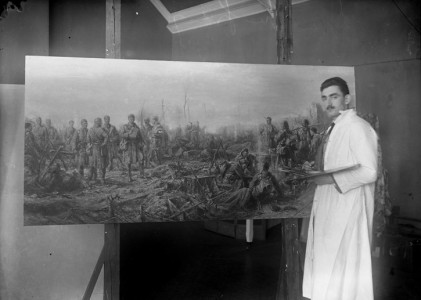

Although the work of Eric Kennington is not always considered alongside prominent artists like David Bomberg, Wyndham Lewis, Paul Nash, John Singer Sargent or Spencer, yet I think of him as an outstanding artist of the First World War. He served first as a soldier in France in 1915, only in 1917 becoming an official British war artist, and then commissioned by the Canadian War Memorials Scheme in November 1918. He also served as a war artist in the Second World War.

Gassed and Wounded replays elements of Kennington’s earlier, famous and brilliant painting in oil on glass, The

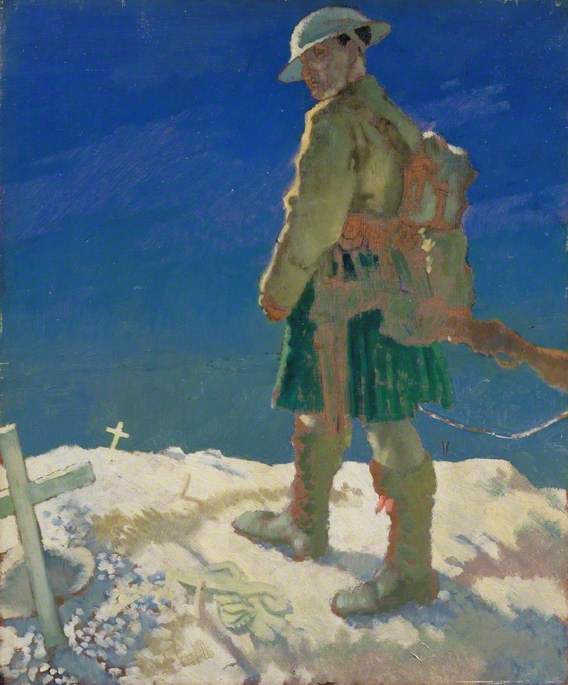

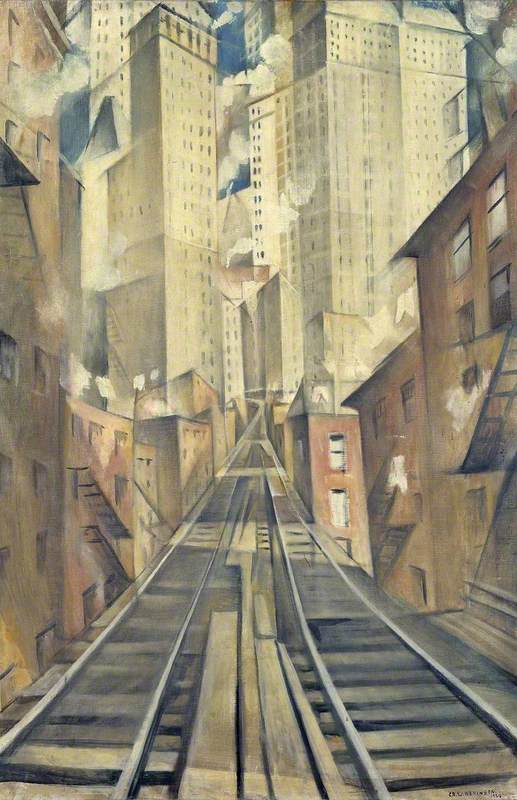

The depiction of the suffering of ordinary soldiers was extended in Eric Kennington’s large-scale 1920 painting for the Canadian War Memorials Scheme, which he titled The Victims. But he had to accept it being retitled as The

The Conquerors

1920, oil on canvas by Eric Henri Kennington (1888–1960)

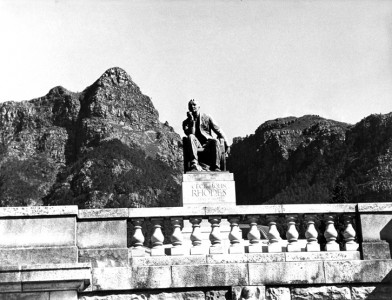

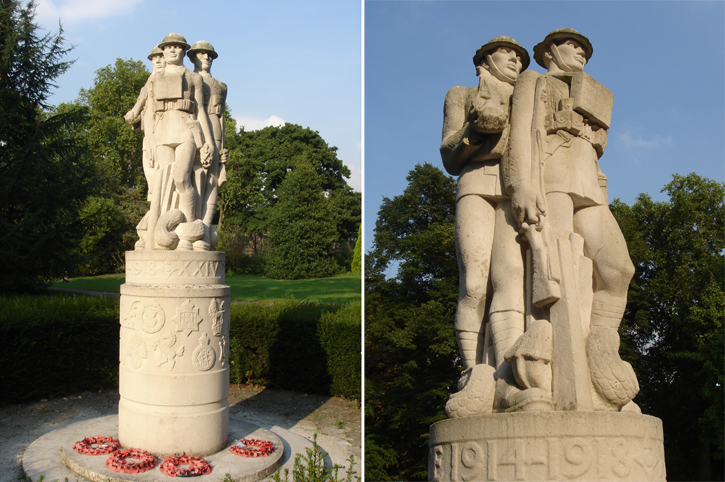

After the war, Eric Kennington was approached by the commander of the 9th Royal Sussex, Lt Col M. V. D. Hill – who I knew later as Victor Hill, a retired solicitor – who asked if he knew of any suitable sculptors to carve a memorial for the 24th East Surrey Division, to be installed in Battersea Park. Kennington responded by asking if he might carve it himself. The memorial was unveiled in 1924, though the Division had disbanded in 1919, having suffered the loss of over 35,000 men killed, wounded and missing.

The stone figures are carved as stylised modern portraits, but of particular soldiers: Trooper Morris Clifford Thomas of the Machine Gun Corps, Sergeant J. Woods of the 9th Battalion, Royal Sussex and (the writer) Robert Graves of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers.

Memorial to the 24th Division, Battersea Park, London

1924, Portland stone by Eric Henri Kennington (1888–1960)

When I questioned Victor Hill about the symbolism of the large serpent entwined around the soldiers’ legs, he said the snake represented ‘Mud, blood

Eric Kennington came strongly to mind when I recently watched the extraordinary First World War documentary by Peter Jackson (of Hobbit films fame), titled They Shall Not Grow Old. It is based on original film footage from the Imperial War Museum archive, but now cleaned,

'Peter Jackson has created a visually staggering thought experiment; an immersive deep-dive into what it was like for ordinary British soldiers on the western front. This he has done using state-of-the-art digital technology...

'The effect is electrifying. The soldiers are returned to an eerie, hyperreal kind of life in front of our

As Peter Jackson intends, so Eric Kennington had desired – for viewers to be left contemplating the futility of war, as well as admiring the exceptional courage of ordinary soldiers, selflessly serving their country.

Sandy Nairne, curator, writer and former Director of the National Portrait Gallery