O the Roast Beef of Old England is perhaps one of Hogarth's most famous paintings – it's also one of his most overtly patriotic. While visiting France in 1748, Hogarth was arrested as a suspected spy in Calais when he was discovered sketching the fortifications and this painting wryly marks the occasion.

His self-portrait appears in the background, a hand resting ominously on his shoulder, while in the centre a great hunk of beef, symbolising British prosperity, is contrasted with scrawny French soldiers and watery soup on the one hand, and on the other, a salivating Catholic friar and a group of superstitious fisherwomen who believe they've seen Christ in a flatfish.

The painting tells a 'good' story and Hogarth carefully positions himself as a keen social observer, indeed it has many of the characteristics that make Hogarth one of Britain's most well-loved artists – wit, irreverence, an unflinching candour and immediacy.

These traits have become synonymous with Hogarth, even part of his brand ('Hogarthian' was in use even in his lifetime), but more than that they seem to typify Hogarth, a born and bred Londoner, as a 'true Brit' and 'father' of English painting.

Yet, if we look again at O the Roast Beef, we might also note that the luscious detail of the meat and fish seems indebted to the still life paintings of Jean-Siméon Chardin, whose studio Hogarth had visited in Paris. The strong framing archway and recognisable setting can be associated with the city views that Venetian painter, Canaletto, had increasingly popularised since his arrival in London in 1746.

Still Life: The Kitchen Table

c.1755–1756

Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin (1699–1779)

The anti-French imagery and stereotypes it trades in draw upon the accounts of the large Huguenot (French protestant refugee) community in London, with which Hogarth had close connections. The image itself was widely reproduced and circulated in print too, as Hogarth produced engravings after many of his works for the mass market, and even on Chinese export porcelain. It is not long then before the picture's distinct nationalism is unsettled by the connections that extend far beyond Britain alone.

What emerges is a far richer picture: of Hogarth as an artist deeply engaged with European art, and of eighteenth-century culture as far more cosmopolitan and connected than we might at first think. This gets to the heart of the Hogarth and Europe exhibition at Tate Britain, which displays Hogarth's art in a fresh light alongside works by his Continental contemporaries, including Watteau in Paris, Pietro Longhi in Venice and Cornelis Troost in Amsterdam.

While the idea that Hogarth knew and admired European art is longstanding, the opportunity to test this on the walls, to see the crosscurrents, exchanges and divergences in the flesh, is new and not entirely predictable. Through this, the show seeks to explore how artists across Europe grappled with and gave visual expression to the rapid social, economic and cultural changes of the eighteenth century – its freedoms and opportunities as much as its contradictions, exploitation and injustices.

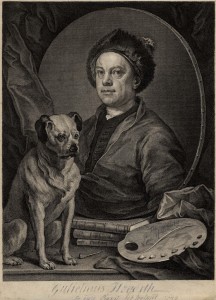

These changes can be detected in the ways in which artists imagined themselves as they navigated working more like freelancers, enjoying more creative freedom but at the same time becoming more financially vulnerable. Hogarth's Self-portrait Painting the Comic Muse, for example, highlights the artist's desire to be viewed as a serious comic painter (Thalia, the Muse of Comedy is on his canvas), but perhaps self-consciously and a little humorously it also evokes the visual tradition of Singerie, where monkeys are often portrayed painting – this was certainly a link that his contemporary critics made! The French painter Étienne Jeaurat on the other hand shows an artist's students warming their hands against the fire, tracing against a window or poring over drawings.

Or these shifts can be seen in the way that artist's portrayed others. Francis Matthew Schutz is rather surprisingly shown by Hogarth hungover and vomiting into his bedpan, the painting apparently commissioned by his wife who was fed up with his drinking and womanising. Yet while Hogarth's irreverence might appeal to some patrons, particularly men who flattered themselves that they were free-thinking, independent and witty – in on the joke and powerful enough to withstand the rough treatment – he could also bring remarkable sensitivity to his portraits.

His portrait of his servants is arresting in its naturalism and directness, seeming to capture their character and distinct identities. In this respect, it may reflect new ideas of individuality emerging in the eighteenth century, including in this instance the often-marginalised working class. But it may also reflect the market forces at work, as Hogarth may have used it to advertise his skills to potential portrait clients.

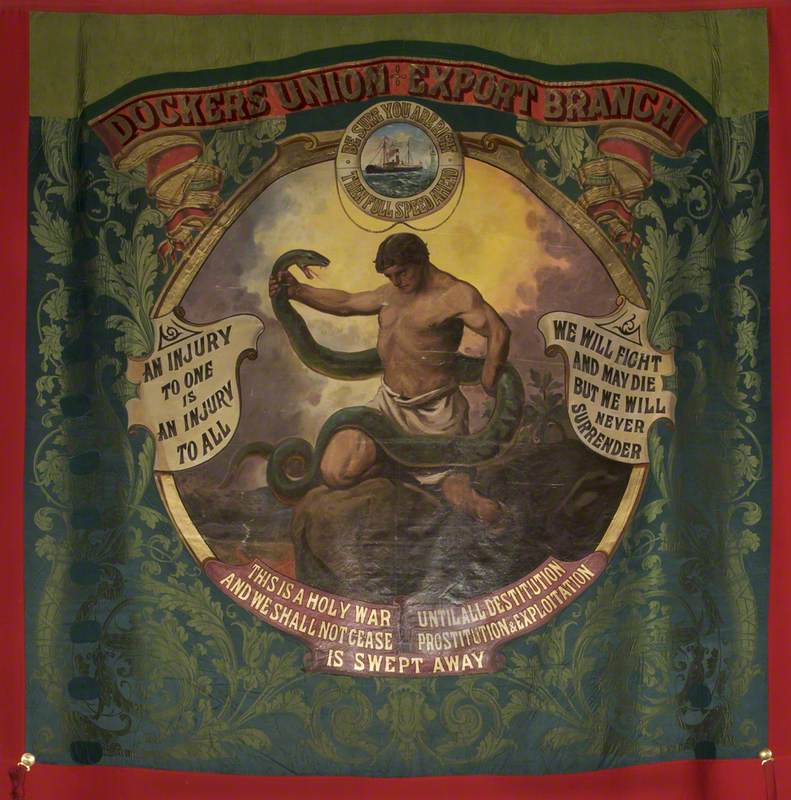

Or these tensions become apparent through the imagery itself. A Midnight Modern Conversation comically depicts the late-night revelry and conviviality of drunken men, bringing the 'Hogarthian' into sharp focus. Although Hogarth's original is now lost, the image was highly popular, reproduced in print, extensively copied and widely circulated. Looking more closely, though, the rum punch being drunk and the sugar that sweetens it, the tobacco being smoked, all point to the global networks of trade, commerce and empire that underpinned European culture and consumption, and the stark inequities and violence this entailed.

A Midnight Modern Conversation

(after a lost original, engraved in 1733)

William Hogarth (1697–1764) (after)

Perhaps most tellingly though, these changes are evident in the ways in which artists – and none more so than Hogarth – took on new roles as social commentators. Today, Hogarth is best known for his 'Modern Moral Series', which traces the fortunes of a character over a series of pictures – as in Marriage A-la-Mode which depicts the unhappy consequences of a marriage of convenience.

Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête

about 1743

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Money is exchanged for status and Hogarth fills the paintings with lavish details that suggest the corrupting influence of wealth and materialism. But all his series speak to the social types and preoccupations of the day and, significantly, are located in recognisable places across London. They exemplify how artists were working increasingly entrepreneurially, able to address a far larger, urban audience directly, and were able to tell their own stories that might reflect and critique society.

We hope that these threads will be evident throughout the exhibition and that the art on display offers a glimpse into the ways in which artists engaged with the new modern experience.

Alice Insley, assistant curator of historic British art at Tate Britain

'Hogarth and Europe' at Tate Britain runs until 20th March 2022