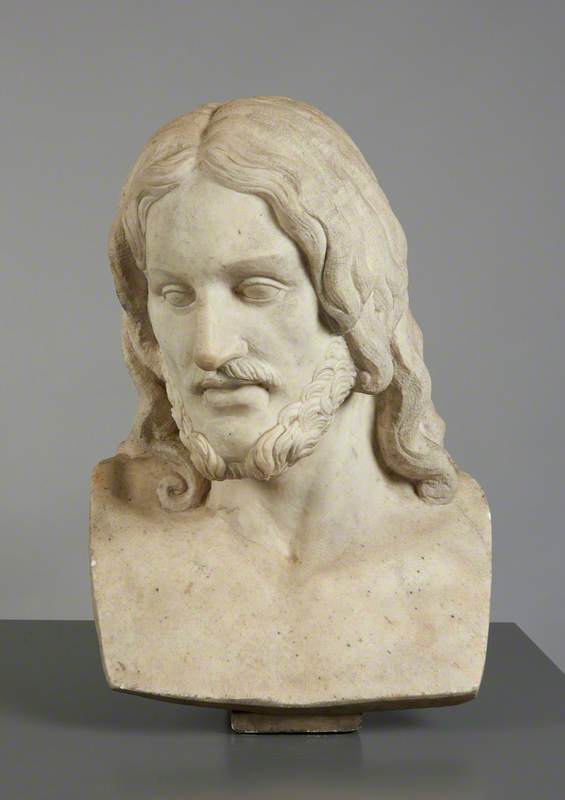

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564)

Wellcome Collection

(Born Caprese [now Caprese Michelangelo], nr. Arezzo, 6 March 1475; died Rome, 18 February 1564). Florentine sculptor, painter, architect, draughtsman, and poet, one of the giants of the Renaissance and, in his later years, one of the forces that shaped Mannerism. Michelangelo's career lasted more than 70 years and for most of that time he was the dominant figure in Italian art. His contemporaries regarded him with awe, and the word terribilità, which may be translated as ‘terrifying intensity’, was often applied to his work. He was the subject of two detailed biographies in his lifetime, both of them by people who knew him well (Vasari and Condivi), and because of these and other sources (including his own letters, about 500 of which survive), more is known about him—his personal qualities as well as the details of his career—than about any previous artist. He was utterly devoted to art and religion, living frugally in spite of his fame. However, although he was scornful of the conventional trappings of success, he was sure of his own worth and was concerned about his place in society. He tended to be suspicious and withdrawn, and had a sharp temper and a sarcastic tongue, but he was affectionate and generous to his family and friends. His father, a member of the gentry, claimed noble lineage and throughout his life Michelangelo was touchy on the subject: pride of birth had much to do with the family opposition to his choice of an artistic career as well as with Michelangelo's own insistence on the status of painting and sculpture among the liberal arts.

After the death of Lorenzo de' Medici in 1492 the political situation in Florence became unstable, and in October 1494 Michelangelo moved to Bologna, where he carved three small figures for the shrine of St Dominic (see Niccolò dell'Arca). He returned to Florence in 1495 but in June 1496 moved to Rome, where he remained for the next five years and where he carved the two statues that established his fame when he was still in his early twenties—Bacchus (c.1496–7, Bargello, Florence) and the Pietà (1498–9, St Peter's, Rome). The latter is the masterpiece of his early years—a tragically expressive and yet beautiful and harmonious solution to the problem of representing a full-grown man lying dead in the lap of a woman. There are no marks of suffering—as were common in northern representations of the period—and the carving has a flawless beauty and polish demonstrating his absolute technical mastery.

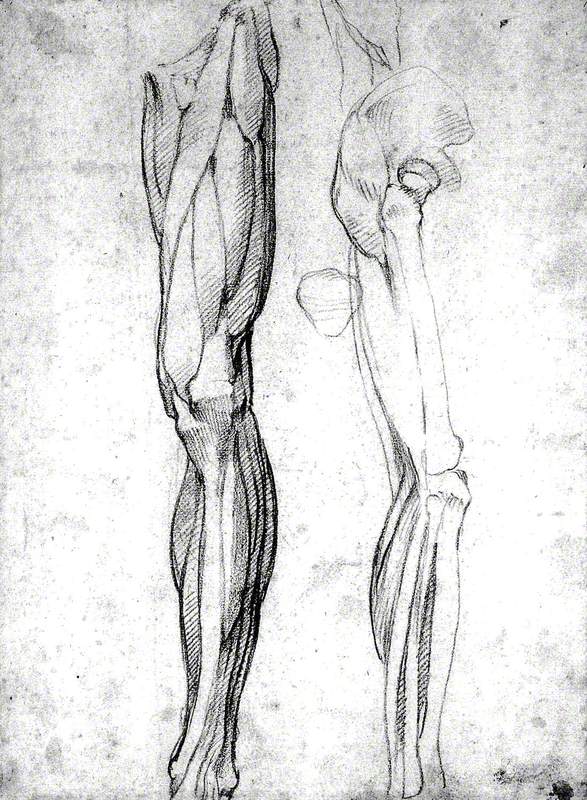

For unclear reasons, Michelangelo returned to Florence in 1501, leaving unfinished an altarpiece of the Entombment commissioned by the church of S. Agostino, Rome (NG, London), one of only two or three surviving panel paintings by him (see tondo). He remained in Florence until the spring of 1505, the major completed work of the period being the marble David (1501–4, Accademia, Florence), which has become a symbol of Florence and Florentine art (it was originally intended for the cathedral but was instead set up outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of government, David being regarded as a virtuous fighter for freedom, as the citizens of the Florentine republic liked to see themselves). Soon after the David was completed, Michelangelo received another great commission from the Florentine government—a huge mural of the Battle of Cascina for the new Council Chamber in the Palazzo Vecchio; here he worked in rivalry with Leonardo, who was engaged on the Battle of Anghiari for the same room. Neither painting came to fruition, but Michelangelo completed the full-size cartoon or part of it, and during its brief life this was highly influential (Vasari says that it was ‘torn apart and divided into many pieces’ because it was ‘placed too freely in the hands of artists’). It is now known through a copy of the central section, as well as from some magnificent preliminary drawings (for example in the British Museum, London).

Michelangelo left the battlepiece unfinished when Pope Julius II (Giuliano della Rovere) summoned him to Rome in 1505 to make his tomb. However, the following year Julius began the rebuilding of St Peter's, which deflected his attention from the tomb, and at his death in 1513 little had been accomplished on it. Afterwards the project dragged on for decades, causing Michelangelo to lament, ‘I have wasted all my youth chained to this tomb.’ It was originally conceived on the most grandiose scale, but was whittled down in successive contracts with Julius's heirs, and of the monument finally erected in S. Pietro in Vincoli, Rome, in 1545 only three figures, including the celebrated Moses (c.1515), are from Michelangelo's own hand. (Two figures of Slaves, c.1513, carved by Michelangelo for the tomb are now in the Louvre, Paris.)

The other great work commissioned from Michelangelo by Julius—the frescoing of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (1508–12)—was equally daunting, but was brought to sublime fruition. Michelangelo, who always regarded himself as a sculptor first and foremost, was reluctant to undertake the work, but he made of it his most heroic achievement, not only for its quality as a work of art, but also in terms of the endurance and stamina he showed in completing so quickly and virtually unaided such a huge and physically uncomfortable task. There is still much debate about the exact interpretation of the scores of figures that adorn the ceiling, but the main images represent scenes from Genesis, from the Creation to the Drunkenness of Noah, forming the background to the frescos on the life of Moses and of Christ on the walls below by a number of 15th-century artists (see Perugino). Prophets and Sibyls who foretold Christ's birth are at the sides of the ceiling, and at each corner of the central scenes are figures of beautiful nude youths (usually called the Ignudi). Their exact significance is uncertain, but as Kenneth Clark wrote, ‘Their physical beauty is an image of divine perfection; their alert and vigorous movements an expression of divine energy.’ From the moment of its completion the ceiling has always been regarded as one of the supreme masterpieces of pictorial art (the cleaning in the 1980s revealed anew the beauty of the colouring), and Michelangelo, at the age of 37, was recognized as the greatest artist of his day, a position he retained unchallenged until his death half a century later.

In 1516 Michelangelo was commissioned by Julius II's successor, Leo X (Giovanni de' Medici), to design a façade for the Medici parish church in Florence, S. Lorenzo, which had been left unfinished by Brunelleschi. The project came to nothing and wasted a good deal of Michelangelo's time, but it led to two other works for S. Lorenzo—the Medici Chapel, or New Sacristy, planned as a counterpart to Brunelleschi's Old Sacristy, and the Biblioteca Laurenziana, which houses the Medici collection of books and manuscripts. Neither project was completed in accordance with Michelangelo's plans, but they nevertheless rank among his finest creations. He began work on the Medici Chapel in 1519, broke off when the Medici were expelled from Florence in 1527, restarted in 1530, and left the work incomplete in 1534 when he settled permanently in Rome. The powerful architectural forms of the building are conceived as the setting for the wall tombs of Giuliano and Lorenzo de' Medici, who are characterized in their marble figures as representatives of the Active and Contemplative Life; below them are allegorical reclining figures symbolizing Day and Night (for Vita activa) and Dawn and Evening (for Vita contemplativa). Anthony Blunt has written of the Medici Chapel sculptures: ‘there is still that superhuman quality visible in the Sistine frescoes…but in addition there is a feeling of brooding, of sombre disquiet, which becomes from this time a hall-mark of Michelangelo's work. They are no longer only symbols of eternal beauty; they also reflect the tragedy of human destiny.’

In the 30 years that remained to him in Rome, Michelangelo worked mainly for the papacy. He was at once commissioned to paint the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel and began the actual painting in 1536. It was unveiled on 31 October 1541, 29 years to the day after the unveiling of the Sistine Ceiling but a whole world away from it in feeling and meaning, with its massive and menacing figures and mood of wrathful desolation. In the interval the world of Michelangelo's youth had collapsed in the horror of the Sack of Rome (1527), and its confident humanism had been found insufficient in the face of the rise of Protestantism and the new, militant spirit of the Counter-Reformation. For Paul III (Alessandro Farnese), who commissioned the Last Judgement, Michelangelo also executed his final works in painting, the Conversion of St Paul and the Crucifixion of St Peter (1542–50), frescos in the Cappella Paolina (Paul's private chapel) in the Vatican. The figures here are even more blunt, heavy, and unconcerned with physical allure, totally repudiating his own early ideals.

Something of the same deep and troubled spirituality is seen in Michelangelo's late drawings of the Crucifixion and in two sculptures known as Pietàs (although they might more accurately be described as representing the Deposition). One (now in Florence Cathedral) was intended for his own tomb and contains a self-portrait as Nicodemus; it was begun c.1546 and mutilated and abandoned by Michelangelo in 1555. The other, known (from the name of former owners) as the Rondanini Pietà (Castello Sforzesco, Milan), was his last work, left unfinished at his death.

For the last twenty years of his life, however, Michelangelo devoted himself mainly to architecture, and in this field his stature is scarcely less great than in sculpture and painting (no other artist has approached this domination in the three major visual arts). His most important commission—indeed the most important in Christendom—was the completion of St Peter's, which had been begun under Julius II in 1506. When Michelangelo became architect in 1546, the building had advanced little since Bramante's death in 1514. As with the Sistine Ceiling, he was initially unwilling to undertake the task, but he then proceeded with formidable energy and by the time of his death, work had advanced so far that the drum of the dome was nearly complete. Michelangelo also designed the dome itself, but as executed after his death it is probably a good deal steeper in outline than he intended. The addition of a long nave in the early 17th century altered Michelangelo's plan for a centralized church, but nevertheless the exterior of the building owes more to him than to any other architect and forms a fitting conclusion to his titanic career.

In architecture, Michelangelo's decorative vocabulary soon attained widespread currency, but it was only in the 17th century that his massive and dynamic style was fully appreciated and emulated; it is fitting that it fell to Bernini, the great sculptor-architect of the age, to complete St Peter's with his glorious piazza. In painting and sculpture, Michelangelo's means of expression was limited almost entirely to the heroic male figure, usually nude, but in this domain he reigned supreme as no artist has done before or since, and for centuries afterwards it was virtually impossible for any artist to work in the field without referring, consciously or unconsciously, to his example.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)