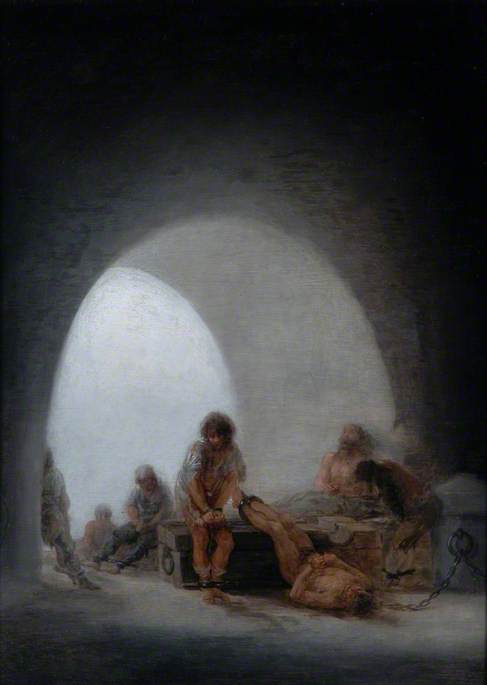

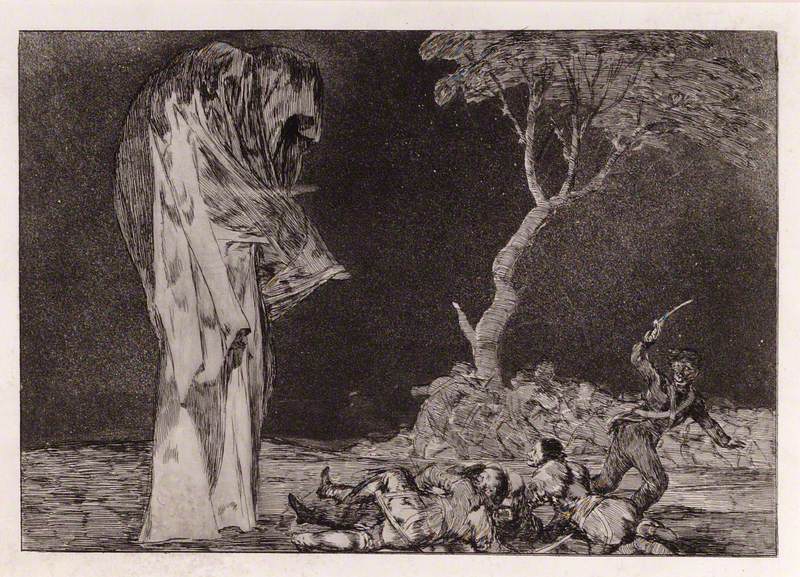

Disparate de miedo c.1816–1823

Francisco de Goya (1746–1828)

The Higgins Art Gallery & Museum, Bedford

(Born Fuendetodos, nr. Saragossa, 30 March 1746; died Bordeaux, 16 April 1828). Spanish painter, printmaker and draughtsman. He was the most powerful and original European artist of his time, but his genius was slow in maturing and he was well into his thirties before he began producing work that set him apart from his contemporaries. The son of a gilder, he trained initially with a local painter in Saragossa, then in 1763 moved to Madrid, where he continued his studies under Francisco Bayeu (he twice failed in attempts to enrol at the Academy of San Fernando). After a visit to Italy (c.1768–71), he worked in Saragossa, then after marrying Bayeu's sister in 1773 he settled in Madrid in 1774. Bayeu secured him employment making designs for the royal tapestry factory, and this took up most of his working time from 1775 to 1780 (he continued the work more sporadically until 1792). Goya made 63 tapestry designs in all (most of them are in the Prado, Madrid). Although they are usually referred to as ‘cartoons’, they are in fact finished oil paintings, many of them of impressive size (the largest are more than 6 m (20 ft) wide). The subjects range from idyllic scenes to realistic incidents of everyday life; they are conceived in a lively and romantic spirit and executed with Rococo decorative charm, but they are sometimes spiced with a sardonic humour that looks forward to Goya's later work.

In 1795 Goya succeeded Bayeu as director of painting at the Academy of San Fernando and in 1799 was appointed principal painter to the royal household, producing his famous portrait group, the Family of Charles IV (Prado), in the following year. The weaknesses of the royal family are revealed with unsparing realism, though evidently without the deliberate satirical intent that has sometimes been claimed for the picture. Goya's early portraits had followed the manner of Mengs, but stimulated by the study of Velázquez's work in the royal collection he developed a much more natural, lively, and personal style, showing increasing mastery of pose and expression, heightened by dramatic contrasts of light and shade. From about the same date as the royal group portrait are the celebrated pair of paintings the Clothed Maja and Naked Maja (Prado), whose erotic nature led Goya to be summoned before the Inquisition. Popular legend has it that they represent the Duchess of Alba, the beautiful widow whose relationship with Goya caused scandal in Madrid.

During the French occupation of Spain (1808–13) Goya retained his appointment of royal painter under Joseph Bonaparte (installed as king by his brother Napoleon), but his activity as a painter of court and society decreased, and—like many others—he may have had mixed feelings about the occupation, torn between welcoming the regime (which potentially brought freedom from royal tyranny) and feeling patriotic abhorrence against foreign military rule. He never openly expressed his political opinions and to a certain extent he was prepared to bend with the prevailing wind for the sake of his career (during the occupation he painted the Duke of Wellington, Napoleon's eventual conqueror, as well as supporters of the French). After the restoration of Ferdinand VII in 1814 Goya was exonerated from the charge of having ‘accepted employment from the usurper’ by claiming he had not worn the medal awarded him by the French, and he painted for the king two powerful and harrowing pictures of Spain's ‘glorious insurrection’, the bloody uprising of the citizens of Madrid against the occupying forces—The Second of May, 1808 and The Third of May, 1808 (both 1814, Prado). Even more savage are the 65 etchings Los desastres de la guerra (The Disasters of War, 1810–14), which depict atrocities committed by both French and Spanish.

Goya virtually retired from public life after 1815, subsequently working for himself and friends. He kept the title of court painter but was superseded in royal favour by Vicente López. Towards the end of 1819 he fell seriously ill for the second time (a remarkable self-portrait in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts shows him with the doctor who nursed him). Earlier that year he had bought a country house in the outskirts of Madrid, the Quinta del Sordo (House of the Deaf Man); and it was here, after his recovery, that he executed fourteen large murals (now in the Prado) known as the Black Paintings (1820–3) on account of their nightmarish subjects as well as their dark tonality. Painted almost entirely in blacks, greys, and browns, they feature religious and mythological scenes as well as ones entirely from Goya's imagination; they are executed with an almost ferocious intensity and freedom of handling and have been seen as reflections on death. By the time he completed these extraordinary works, many Spanish liberals were leaving the country because of the oppressive regime of Ferdinand VII, and in 1824 Goya obtained permission to visit France, ostensibly for reasons of health, and settled at Bordeaux. He made two brief visits to Spain, on the first of which (1826) he officially resigned as court painter and was granted a pension. In these last years he took up the new medium of lithography (in four bullfighting scenes known collectively as the Bulls of Bordeaux, 1824–5), while his final paintings illustrate his progress towards a style anticipating Impressionism in its freedom and lightness of touch.

Goya's output was enormous: there are about 700 surviving paintings by him, some 300 prints, and nearly 1,000 drawings. He was exceptionally versatile and his work expresses a very wide range of emotion. His technical freedom and originality likewise are remarkable—he sometimes manipulated paint with knives or fingers (and with more unconventional tools, including sponges and a wooden spoon, if Théophile Gautier's account in Voyage en Espagne, 1845, is to be believed), and in his prints he often used more than one technique on the same plate, especially combining etching with aquatint. In his own day he was chiefly celebrated for his portraits (which account for more than half of his painted output), but his exalted reputation now rests equally on work that was virtually unknown to his contemporaries: the Disasters of War etchings were not published until 1863 and the Black Paintings were not publicly exhibited until the 1870s.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)