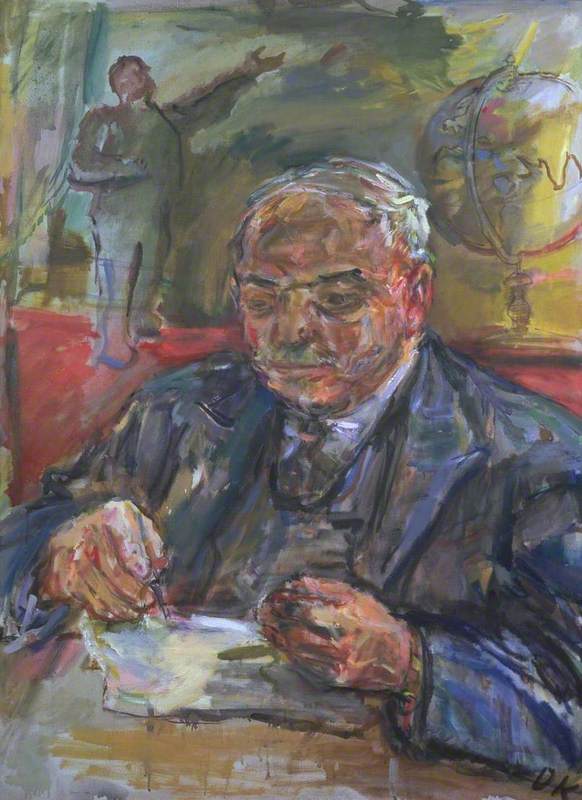

(b Pöchlarn, 1 Mar 1886; d Montreux, Switzerland, 22 Feb. 1980). Austrian Expressionist painter, printmaker, and writer (he became a Czech citizen in 1937 and a British citizen in 1947 but reverted to Austrian nationality in 1975). His formative years were spent in Vienna, where in 1909 he began to make an impact with his ‘psychological portraits’, in which the soul of the sitter was thought to be laid bare. A good example is his portrait of the architect Adolf Loos (1909, Staatliche Museen, Berlin), showing the sensitive, quivering line through which Kokoschka captured what he called the ‘closed personalities, so full of tension’ of his sitters. Later his brushwork became much broader and more broken, with high-keyed flickering colours.

Read more

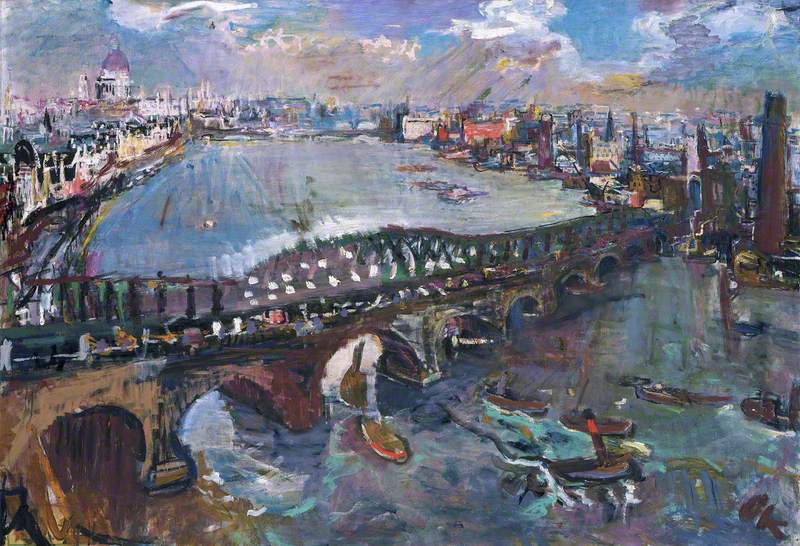

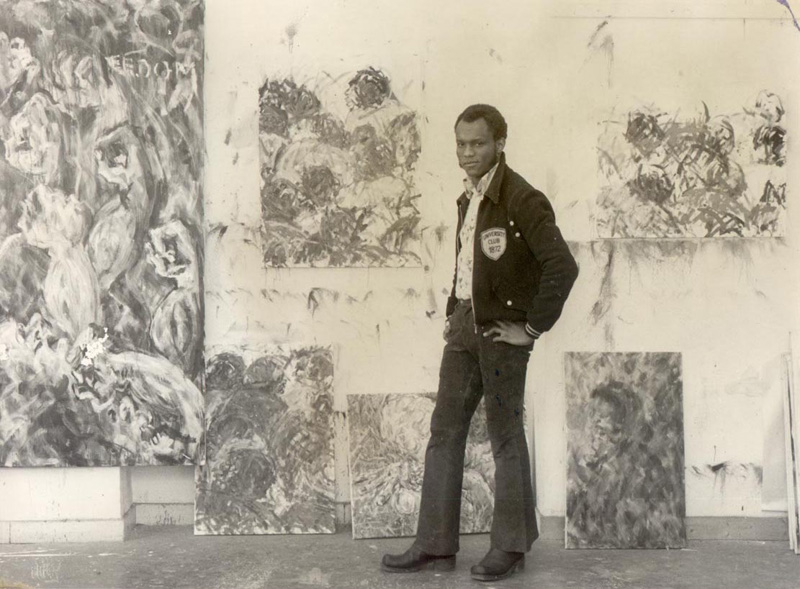

In 1915 he was badly wounded while serving in the Austrian army, and in 1917—still recuperating—he settled in Dresden, where he taught at the Academy from 1919 to 1924. After this he embarked on a period of wide travel that lasted for seven years, and during this time he turned more from portraits to landscapes, including a distinctive type of townscape seen from a high viewpoint (Jerusalem, 1929–30, Detroit Inst. of Arts). In 1931 he returned to Vienna, but he was outspokenly opposed to the Nazis (who later declared his work degenerate) and he moved to Prague in 1934 and then to London in 1938. By this time he had an international reputation, but his work was as yet little known in England and he was poor throughout the war years. After the war his fortunes soon improved and he came to be generally regarded as one of the giants of modern art. From 1953 he lived mainly at Villeneuve in Switzerland, and from 1953 to 1963 he ran a summer school at Salzburg. In his later years he continued to paint landscapes and portraits, but his most important works of this time are allegorical and mythological pictures, including the Prometheus ceiling (1950) for the house of Count Seilern (see Courtauld) at Princes Gate in London, and the Thermopylae triptych (1954) for Hamburg University. Kokoschka remained steadfastly unaffected by modern movements throughout his long life, pursuing his highly personal version of pre-1914 Expressionism. Unlike many other Expressionists, however, he was essentially optimistic in outlook. His writings include an autobiography (1971), and several plays, notably Mörder Hoffnung der Frauen (Murderer Hope of Women), an early example of Expressionist theatre that caused outrage when it was first performed in 1908 because of its violence.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)