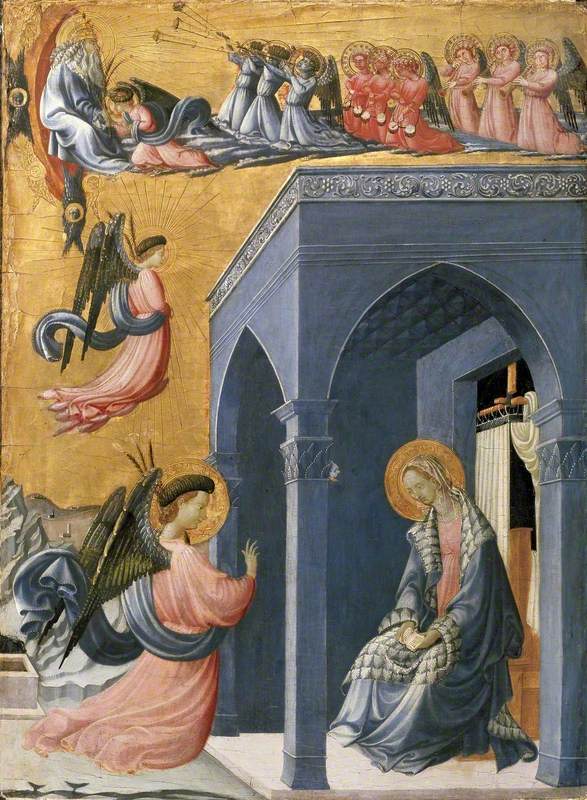

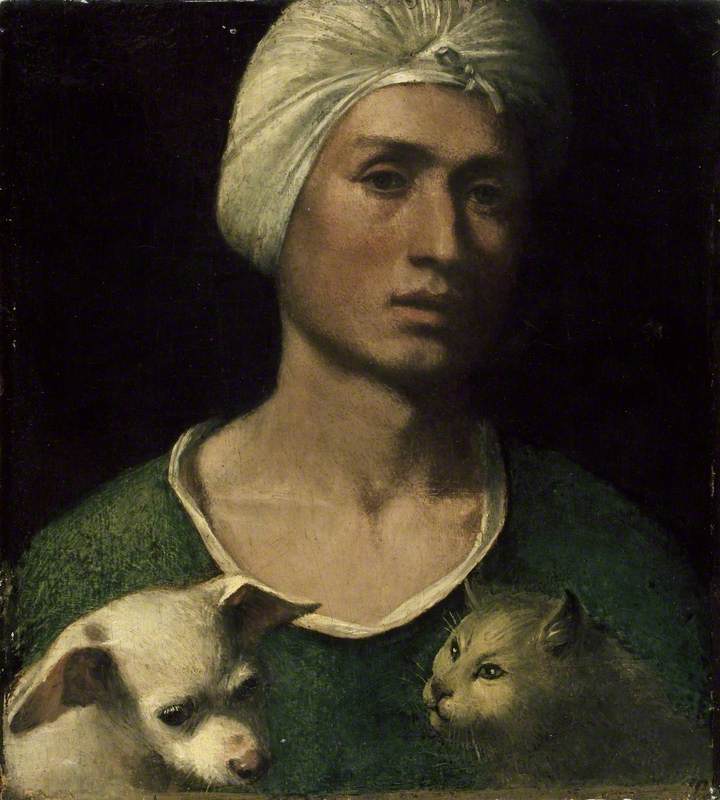

(b Florence, c.1397; d Florence, 10 Dec. 1475). Florentine painter, one of the most distinctive artists of the early Renaissance. Vasari says he was called ‘Uccello’ (which means ‘bird’) because he loved animals, and birds in particular, and he seems to have been regarded as something of an eccentric. He is first documented c.1412 as an apprentice of Ghiberti, but he is not known to have worked as a sculptor. From 1425 to 1427 he is recorded in Venice, where he worked as a mosaicist at St Mark's, but nothing survives there that can be certainly associated with him. By 1431 he was back in Florence, where he spent most of the rest of his life (he worked in Padua, 1444–5, and in Urbino, 1465–8). In 1436 he painted his first dated surviving work—a huge fresco in Florence Cathedral depicting an equestrian statue, a monument to the English condottiere Sir John Hawkwood (d 1394).

Read more

It demonstrates the fascination with perspective that is central to his style. His two other surviving large-scale works are a series of poorly preserved frescos on Old Testament themes (probably 1430s and 1440s) in the ‘Green Cloister’ of S. Maria Novella, Florence, and the Battle of San Romano (c.1440–50), a series of three panels depicting a minor Florentine victory against the Sienese in 1432. The panels—painted for the Bartolini Salimbeni family but seized by Lorenzo de' Medici to decorate his family palace—are now separated, with one each in the National Gallery, London, the Louvre, Paris, and the Uffizi, Florence. Uccello's other works include the decoration of the clock-face and designs for stained-glass windows in Florence Cathedral, and two enchanting paintings that are generally considered to date from late in his career—St George and the Dragon (NG, London), one of the earliest known Italian paintings on canvas, and The Hunt in the Forest (Ashmolean Mus., Oxford). In spite of his major commissions in Florence Cathedral, his career was not particularly successful in worldly terms: Vasari says that ‘he came to live a hermit's life’, and in his tax return of 1469 Uccello described himself as ‘old, without means of livelihood…and unable to work’.Uccello was long regarded more as a curiosity than a serious artist (in 1896 Berenson dismissed him as a mathematician rather than a painter and said that artistically he ‘accomplished nothing’); however, he is now one of the best-loved painters of his time, admired for the power and vigour of his forms, the beauty of his colouring, and his lively and witty imagination. His work presents a striking—and often captivating—combination of two seemingly opposing stylistic currents: the decorative tradition of International Gothic and the scientific involvement with perspective of the early Renaissance. Vasari maintained that Uccello wasted his time ‘on the finer points of perspective’ and presents him as an amiable fanatic who worked into the night and when told to come to bed by his wife would reply: ‘What a sweet mistress is this perspective!’ He undoubtedly took his enthusiasm to extraordinary lengths (in the Battle of San Romano the broken weapons and even the corpses recede neatly in accordance with the perspective scheme), but his effects were appropriate to his subjects and to the decorative charm of his pictures rather than mere technical exercises. In The Hunt in the Forest, for example, he creates not only an atmosphere of fairy-tale romance, but also, through the way in which the horses and dogs move swiftly back into space, an exhilarating sense of darting energy. Uccello's name became so identified with the subject of perspective that he was often said to have invented it: Ruskin, for example, wrote in a letter to Kate Greenaway, ‘I believe the perfection of perspective is only recent. It was first applied in Italian art by Paul Uccello. He went off his head with love of perspective.’

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)