In October 2016, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York opened their major exhibition, Max Beckmann in New York. It featured his art from New York collections, focusing on his final works and connection to the city he described as 'a pre-war Berlin multiplied a hundredfold'. Of the 14 paintings he completed during his last year in New York, Self Portrait in Blue Jacket (1950) is the sole image represented in the exhibition.

View this post on Instagram

There is a certain circularity to this, as Beckmann was walking to see this work exhibited in the exhibition 'American Painting Today' at The Met in 1950 when he died from a heart attack.

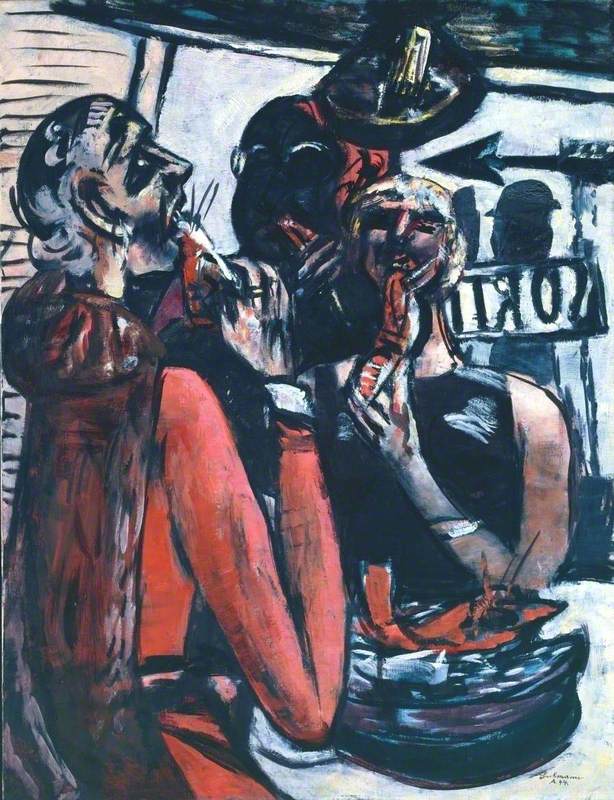

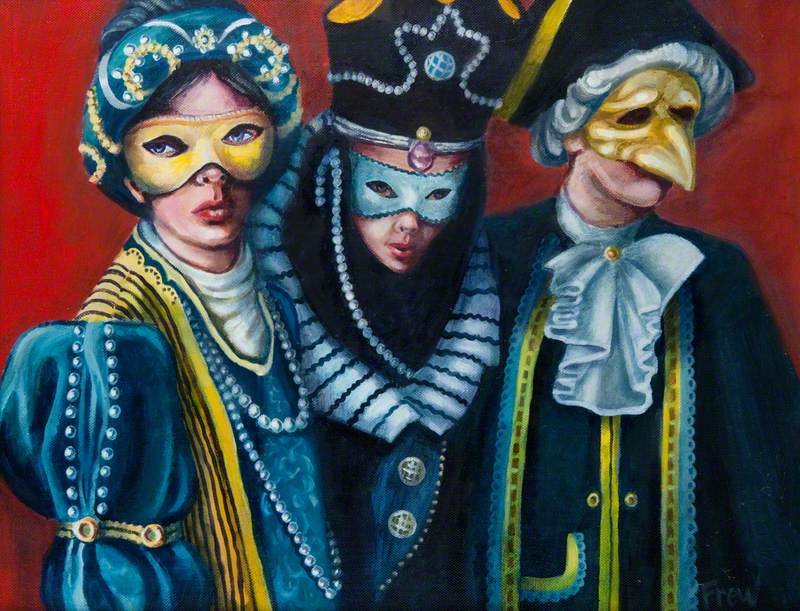

The Leipzig-born artist first achieved success at the height of the Weimar Republic years between the First and Second World Wars. He tried to distance himself from politics following a breakdown during the war, but this proved futile. The First World War and its aftermath had a profound effect on Beckmann and his art, and his severance from previous artistic traditions would redefine him as a Modernist. His 1920 painting, Carnival, from the collection of the Tate Modern, exemplifies the art for which Beckmann would become respected then branded as a 'degenerate' by the Nazi regime.

In 2003, Tate Modern exhibited Carnival as part of the retrospective exhibition 'Max Beckmann', in collaboration with the New York Museum of Modern Art and The Centre Pompidou. Carnival is one of the early works he created five years after his breakdown as a medical orderly in the First World War. He painted it when he returned to Frankfurt am Main, where he had previously gone to recover from the horrific realities he had witnessed and sketched from war-afflicted fields and hospitals on the Belgian front.

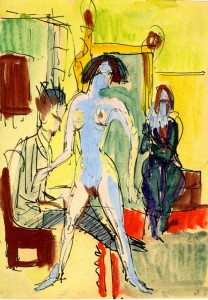

Following his discharge in 1915, Beckmann lived with the painter Ugi Battenburg, whose wife, Fridel Battenburg, also helped with his recovery. She became the subject of many of Beckmann’s paintings and drawings, and he emphasises her importance as the central figure in Carnival with an illusion of almost hierarchical proportion.

The figure on left, I. B. Neumann, was an art dealer and publisher instrumental in supporting Beckmann from early in the artist's career. In a 1921 letter addressed to Neumann, Beckmann acknowledges him as 'the one with the closest and most immediate relationship to my work'. Neumann first exhibited Beckmann before 1919 and became his sole print-dealer by 1921. He was one of the first to promote artists associated with New Objectivity and Expressionism, including Otto Dix, George Grosz and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. In 1923, Neumann opened a gallery featuring German art in New York, 26 years before Beckmann would immigrate there.

The third figure in Carnival is believed to be representative of the artist – Beckmann was a prolific painter of self portraits and portrayed himself in many guises throughout his career. He masks himself as a monkey in a clown costume while lying on the ground with a trumpet between his feet.

The three friends are likely masquerading in the colourful attire of Harlequinade, a British genre of theater that can be traced to sixteenth-century Italian Commedia dell’arte. Neumann could be Harlequin, who loves Battenburg’s character, Columbina, while Beckmann would be the foolish clown her father employs to separate the two. This irrational setting has become a theatre of the absurd and Beckmann’s figure forces us to recognise this madness, a likely metaphor for the outside world. The painting's German title – 'Fastnacht' – is the height of Carnival's celebratory excess before Lent. In 1920, the Frankfurt authorities banned public festivities for Fastnacht, the possible reason this celebration is confined indoors.

The interior in Carnival is the epitome of the structures and perspective in which Beckmann places his figures: claustrophobic, chaotic and on the verge of possible collapse. Much analysis has focused on Beckmann's distinct use of space. The art critic Robert Hughes points to Beckmann's 'horror vacui', or fear of the empty, following what the artist witnessed on the Belgian front.

Beckmann did not return to painting spacious, natural settings or visible horizons as he had done before the war. His sketches from the hospitals and front already reveal the compositional changes seen in his future painting. He had previously been influenced by Cezanne's Post-Impressionism and structured forms, but Beckmann’s use of line became even more jagged and geometric in constricting interiors with illusionistic and disjointed perspective – a comparison that sometimes likened him to Cubist artists.

When Beckmann presented his speech, 'My Theory of Painting', at the New Burlington Galleries in London (1938), he described the 'penetration of space' as a means 'to protect myself from the infinity of space'. Carnival is one of his early paintings in which we see this imposing perspective that seems ordered to diminish space, and one where the figures appear distorted within these surroundings.

By the mid 1920s, Beckmann had become one of Germany's most recognised artists, receiving the Honorary Empire Prize for German Art and Dusseldorf’s Gold Medal of the City. He held a prestigious professorship at Frankfurt's Academy of Art and was exhibited and written about extensively. Beckmann resisted identification with art movements, rejecting Expressionism as critics also began associating him with New Objectivity, the movement that developed in reaction to it.

Many Weimar intellectuals denounced the romantic idealism and emotional interiority bound with Expressionism, particularly after the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European revolutions did not have the impact artists had intended. New Objectivity artists adopted a factual, emotionally removed approach to engage with political critique more effectively.

Yet Beckmann’s use of allegory, myth and symbols complicates this connection and also reminds us of the influence Symbolists like Edward Munch had on his work. In a 1925 letter to his wife, Mathilde 'Quappi' Kaulbach, Beckmann restates his disinterest in being considered a leading figure of New Objectivity because he 'never bothered with groups or movements'.

In 1933, Beckmann's acclaim and association with Expressionism and New Objectivity made him an unfortunate target for Hitler as the Nazi regime denounced and fired him from his teaching post. With more than 500 works confiscated, Beckmann became one of the most attacked artists in Hitler’s notorious 'Degenerate Art' exhibition in 1937. The day after Hitler’s radio speech on the 'merciless war' he was declaring on 'degenerates', Beckmann fled to the Netherlands, where he would spend the next ten years in exile. Amid the hardship of bombings and threat of being drafted into the Second World War, he remained productive and created some of his most powerful work.

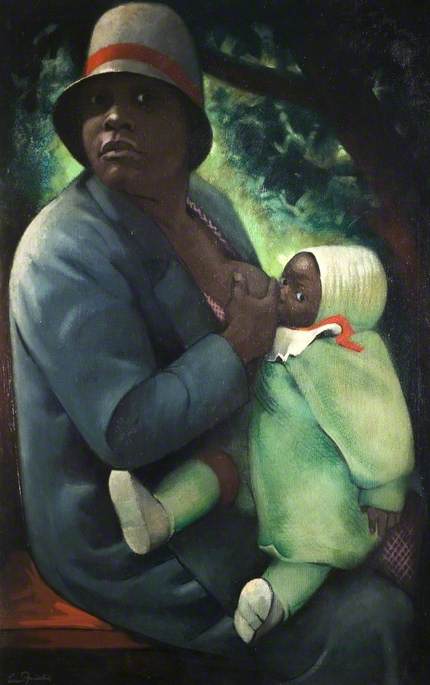

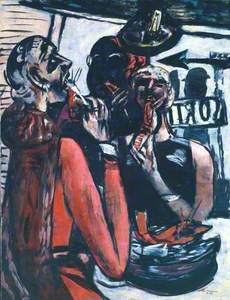

Prunier, also exhibited in the 'Max Beckmann' exhibition at Tate Modern, reminds us of his past through the lens of harsh wartime conditions.

Between 1929 and 1933, Beckmann visited The Prunier, a Parisian restaurant that still specialises in seafood, a delicacy he was known to appreciate to the extent of using it as a motif in his work. As the Weimar Republic years were prosperous for him, his journal entries recount the experiences and meals of this illustrious period before wartime austerity. Beckmann would not return to The Prunier in Paris until 1947 with the author and art collector Stephen Lackner. We first see preliminary sketches for Prunier in Beckmann’s journal in February 1944 under the initial title The Gobblers.

The central figures in Prunier are two seated, well-dressed women who are eating lobster, suggesting affluence. Beckmann had previously portrayed fish in still lifes such as Big Fish Still Life (1927), and would depict women eating seafood again in Ballet Rehearsal (1950), yet never with the illicit and aggressive overtones seen in Prunier. Here the women devour their meal with voracity in an act of spectacle that implies desire and visibility. Beckmann emphasises these dynamics through colour, which he identified as 'the means of expressing the basic emotional temper of the subject'.

In his repetition of red tones, Beckmann draws attention to the women, their act of consuming, and the man who dines near them in shadow. In the foreground, the scarlet in the woman's dress is repeated through each course until it continues to the bespectacled man who appears to face her and the woman to her right. Beckmann paints him and the man outside in silhouette, without the chromatically distinct reds and violets surrounding the women.

In London, Beckmann spoke of his bold contrast and its implications in his work. 'All things come to me in black and white like virtue and crime. Yes, black and white are the two elements which concern me.' Beckmann seems to extend this contrast to visibility in Prunier. Both women seem pictorially closer with distinguishable features while the one further back is placed in direct light. Yet the male figures are distanced from light and view though they see the women. The passer-by appears to watch from outside of the glass, further complicating the dynamics of visibility and possible voyeurism.

None of the figures in Prunier are identifiable as people Beckmann knew. The woman on the left wears a cloak reminiscent of Beckmann's other figures known for theatrical and mythical associations (such as the king from the triptych Departure 1932–1933), also contributing to the staged feeling of extroversion or exposure. The woman in the dark dress is seated in a pose associated with Quappi, Beckmann's wife whom he also painted in connection to light, but is not generally thought to represent her.

The obscured man closest to the women has sometimes been seen as a foreboding, grim presence. This is possible as Beckmann expressed growing concerns over his own health and mortality. Only five days after beginning Prunier, he suffered from symptoms of the heart condition that would take his life six years later. Yet in speaking of the people in his work, Beckmann reminds us that he emphasises chance over meaning in their interactions. 'My figures come and go, suggested by fortune or misfortune. I try to fix them divested of their apparent accidental quality.'

This allusion to chance extends to the unpredictability of the environment where the possibility of danger seems inherent. The diagonal perspective makes the building's foundation appear unstable as poignant lines surround the figures. Perhaps the most threatening of these images is the dagger-like arrow pointing toward the bespectacled man’s head.

The text on the window, 'Sortie' (French for exit) is common in Parisian establishments, but 'sortie' also refers to a military attack, a double entendre Beckmann was likely aware of. In reading the letters upside down, we also find the word 'Rokin', the street of Beckmann's Amsterdam studio where the supportive gallery director Helmuth Lütjens purchased this painting in 1945 before the Tate acquired it. The 'A' Beckmann includes with his signature in the lower right corner is a reference to the work's completion in Amsterdam.

Three years after painting Prunier, Beckmann emigrated to Saint Louis, Missouri, where he resumed teaching and continued exhibiting his work. He went at the prompting of Perry T. Rathbone, the director of the Saint Louis Art Museum that now holds the largest public collection of Beckmann's art. He eventually settled in New York, becoming a professor at the Brooklyn Museum Art School in 1949.

By the end of his life in Manhattan, he had established himself as an international artist – a painter, printmaker, draftsman, writer and sculptor – who left a legacy that continues inspiring artists and scholars. Beckmann did not have the chance to see Self Portrait in Blue Jacket in a major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but 66 years later the public will.

Maria Landsberg, art historian