London-based contemporary artist Yinka Shonibare was born in 1962 in London. He moved to Nigeria with his family when he was three years old, only to return to the UK to do a degree in Fine Art at Byam Shaw School of Art and then Goldsmiths College. Growing up in Lagos had a profound influence on his practice and though he often uses sculpture, he does also turn to photography, film and non-traditional materials to convey his ideas.

Shonibare's works are (almost always) instantly recognisable for his use of brightly coloured textiles – 'African fabrics' – which he has bought at Brixton market for many years. Though not driven to articulate a particular political message, Shonibare uses these fabrics to challenge assumptions of western philosophical and artistic traditions. He often quotes the works of philosophers Edward Said and Jacques Derrida as sources of inspiration when thinking on themes of identity, colonialism and myth.

In his sculptures, Shonibare often dresses his subjects with clothes in eighteenth- or nineteenth-century styles but sewn from these dazzling colourful textiles. These fabrics were in fact introduced to West Africa by Dutch merchants as recently as the 1880s who mechanised Indonesian batik printmaking. The Indonesians were unmoved by the new technology and gave preference to the handmade original. Unable to sell the textiles back to the Indonesians, and to save on the investment, the Dutch started selling the textiles in West Africa. The fabrics grew in popularity and, over time, Africans took ownership of the fabrics, integrating them into their cultures, where different patterns can express a specific identity. By using these fabrics, Shonibare is reviving this chapter of global history, and underlining the role of the west in shaping popular myths of cultural identity globally.

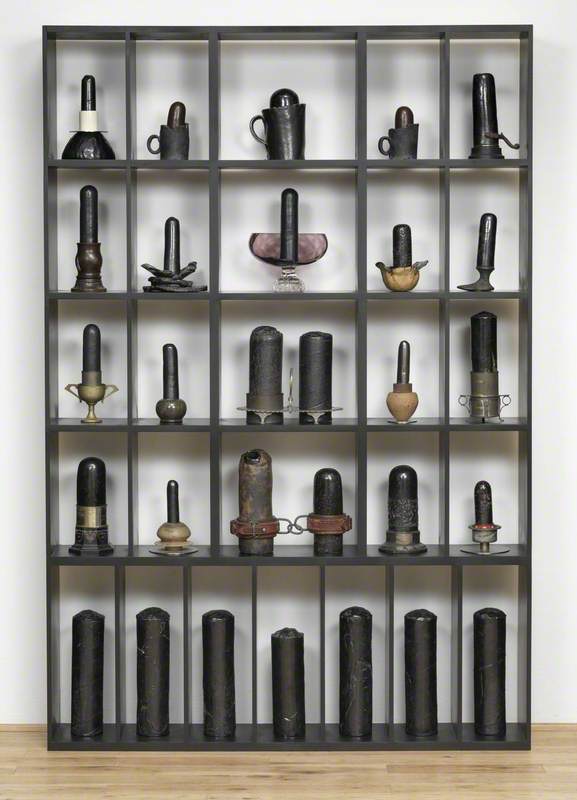

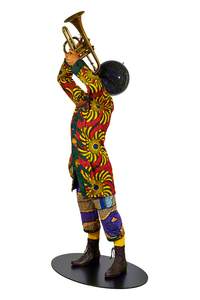

Shonibare's Trumpet Boy – part of the collection at The Foundling Museum – is dressed in a Victorian coat, and cropped trousers, exposing brightly coloured yellow socks, and little, distinctive brown boots. He is the height of a five- or six-year-old and the sense of the real is uncanny, except for the globe head. By using a celestial globe instead of a human head, Shonibare is sparing himself from landing the boy in a specific race or culture, branding him as universal. Furthermore, the star names on the map have been replaced with those of famous musicians of all races, acknowledging the contribution of these artists in the history of music.

Examining the map, the number of names of African origin vastly predominate, with Philip Glass and Madonna sharing the sky with Louis Armstrong, Wynton Marsalis, Ali Ibrahim 'Farka' Toure, to name but a few. Shonibare is literally putting them on the map and rewriting our systems of classification, systems that often favour western culture.

The more obvious connection to music is the boy's hands, which grasp a cornet. The posture of the sculpture indicates an enjoyment in playing the instrument, but also a sense of urgency. His arched back is as though desperately in mid-blow. Though we cannot see the boy's face, he is able, through his pose, to express a sense of innocence and importance, as though blowing a horn in a call to arms.

The sculpture was acquired for The Foundling Museum’s collection by the Art Fund after 'FOUND', a 2016 exhibition curated by Cornelia Parker. In the context of The Foundling Museum, the work underscores the educational aspect of music and how it was used by the hospital, when it was still open, in providing a profession to the child residents. Some of the children went on to play in military bands, having learnt to play in the hospital. In fact, the sculpture is so tender and convincingly childlike that it further underlines the exploitative realities in western history – that of children, as well as colonised peoples.

Maya Binkin, founder of The Art Pilgrim