From minstrelsy to shadow-like figures in the background of otherwise striking works of art, black individuals have often been depicted using sweeping, marginalising imagery. This is not only an issue of a long-forgotten age, but of the alarmingly recent past.

In 2014, socialite-turned-art-gallerist Dasha Zhukova attracted media outcry when she was featured on the digital fashion site Buro 24/7. Her crime? Posing with a contemporary sculpture, widely deemed to be 'racist', by Norwegian artist Bjarne Melgaard.

Dasha Zhukova sitting on a chair made to look like a half-naked black woman was published on Martin Luther King Day pic.twitter.com/SLic3EJjPR

— MAZOE NEWS (@MAZOENews) January 22, 2014

The artwork in question depicted a nearly-naked woman lying on her back, legs en haut; the back of her thighs providing a cosy seat for anyone who goes in for that sort of thing. So far, so harmlessly and delectably controversial. Well, save for the question of misogyny, but that's an issue for another time. The crux of the Zhukova debacle was that this mannequin, who was evidently contorted to chafing point as the heiress perched on top of her, was black. Cue media frenzy.

While it is true that art does not have to be beautiful or flattering to be relevant, the piece in question seemed to fall short in the eyes of many of Zhukova's contemporaries, as well as the wider digital audience.

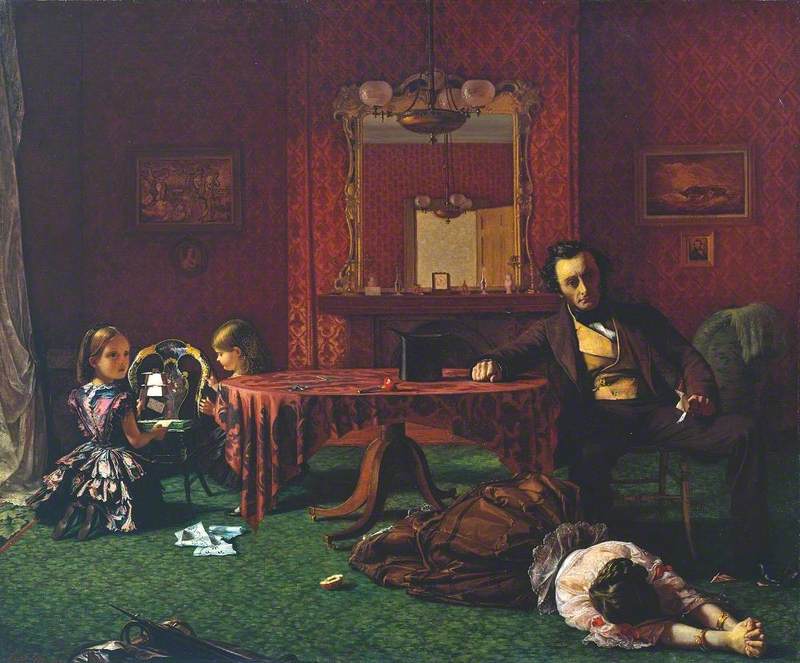

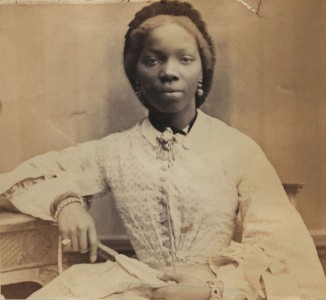

One gnawing fact seemed to be playing out in the collective consciousness; we are not unused to seeing people of colour represented in exotic, uber-sexualised clichés, or in subservient roles, as seen in Charles Philips' portrait of Mary Heldon.

Mary Helden (1726–1766) with a Dog and Her Black Page, 'Sambo'

1739

Charles Philips (1708–1747)

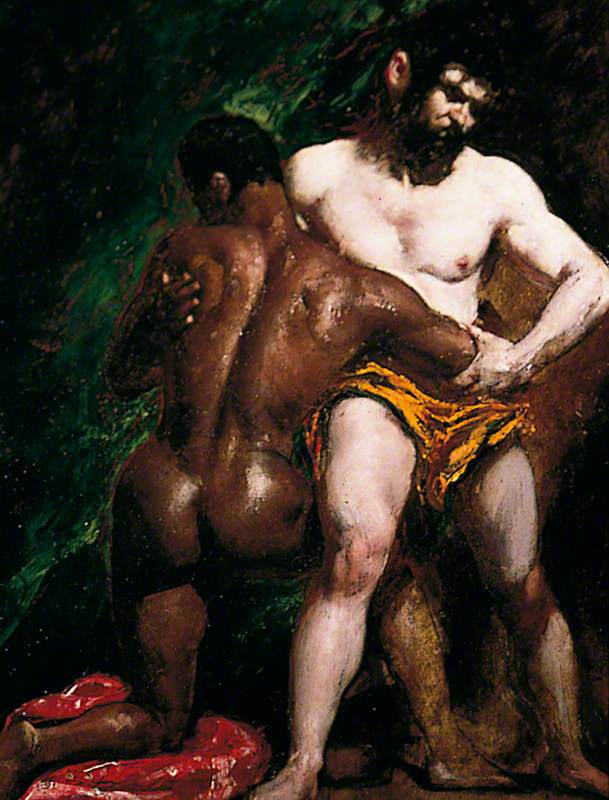

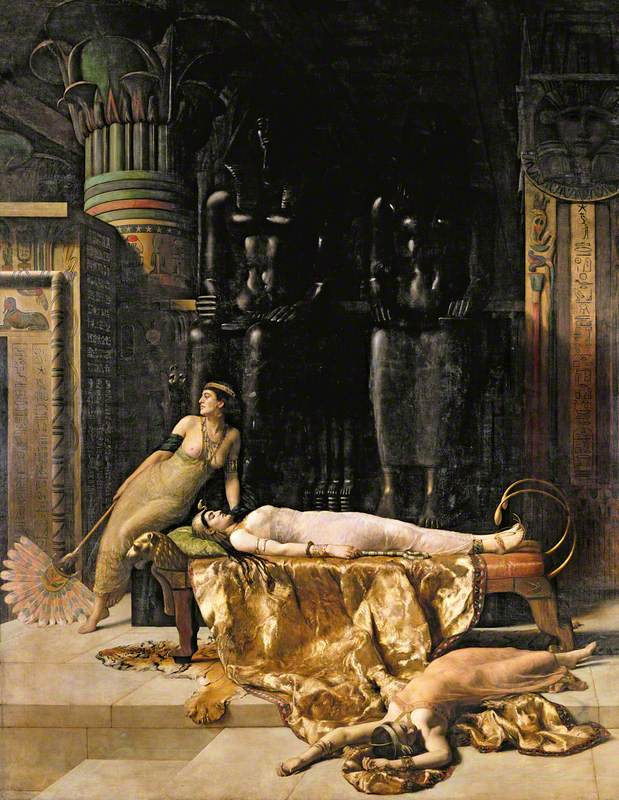

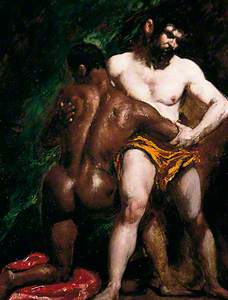

Time was, these depictions were all that we saw of anyone black and brown in art – from this almost endearing (but nonetheless Blackamoor) depiction of A Young Archer, to this blatant nod to Orientalism by William Etty. These trope-y depictions not only seemed inescapable, but everlasting.

But the turn of the nineteenth century saw an increasing number of portraits of blacks presented with a likeness, as opposed to a fantasy. Take, for example, this striking portrait of celebrated black actor Ira Aldridge, dressed in simple yet refined regalia in his role as Othello, by artist James Northcote (1746–1831).

From the portrait's unfussy composition, to the subtle halo-like effect of the pale grey background around his head, it is clear this portrait was painted with dignity and respect in mind.

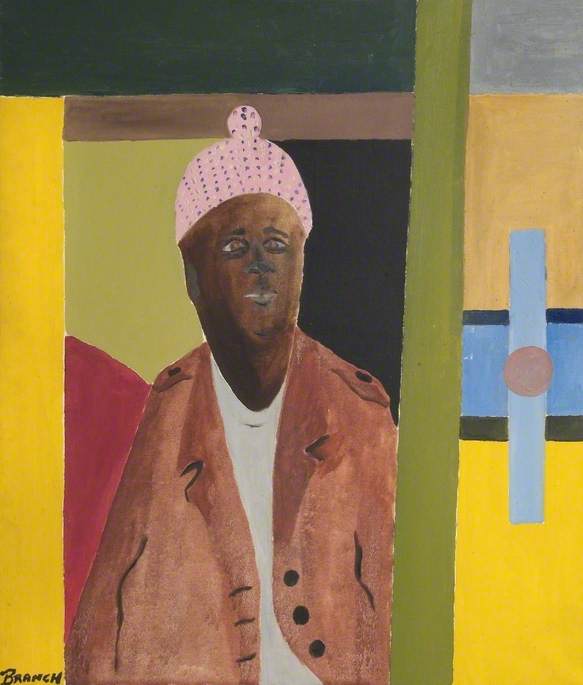

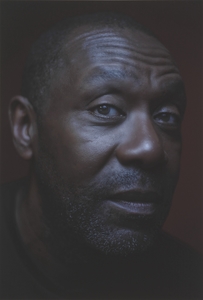

In fact, it is not unlike the elegant portrait of Lord Boateng, a Labour Party politician, depicted by Jonathan Yeo (b.1970). Although, notably, such normalised images of black individuals are of black individuals of considerable renown. In other words, they've had to earn their place of honour on the wall.

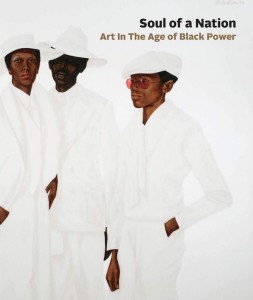

In this vein, the National Portrait Gallery had a recent exhibition of notable black Britons, aptly titled 'Black is the New Black'. The exhibition clearly endeavoured to guide conversation around black culture (and its people) towards a place of understanding and appreciation; tackling the negative by highlighting the positive.

Sir Trevor McDonald (b.1939)

2016

Simon Frederick

Photographer Simon Frederick's images achieve this by showcasing some of Britain's most successful figures from the world of business, politics, fashion, culture, science and religion in celebration of the great and the good from Britain's black community.

'Black is the New Black' follows a fairly new art-world tradition of portraying people of colour in true portraits – and provides a refreshing new take on black Britishness, not least because each interviewee's anecdote is so individual and deeply personal. The offering is a far cry from the usual trigger-friendly (and predictable) single story historically told of black Brits. In fact, one could argue that it renders works like those preferred by Roman Abramovich's ex near obsolete – though that depends on who you ask.

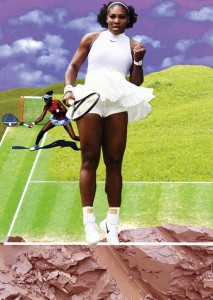

Works that depict black people as outside of subservient, hypersexualised roles – such as those found in 'Black is the New Black' – act as testament to how far society has come.

Like Aldridge and Boateng, those featured (Sir Trevor McDonald, Naomi Campbell, Lenny Henry and Alesha Dixon along with 36 others) sit poised in closely-cropped framing, looking pensive – and, yes, very beautiful indeed – for no other reason than their brilliance.

Patricia Yaker Ekall, journalist