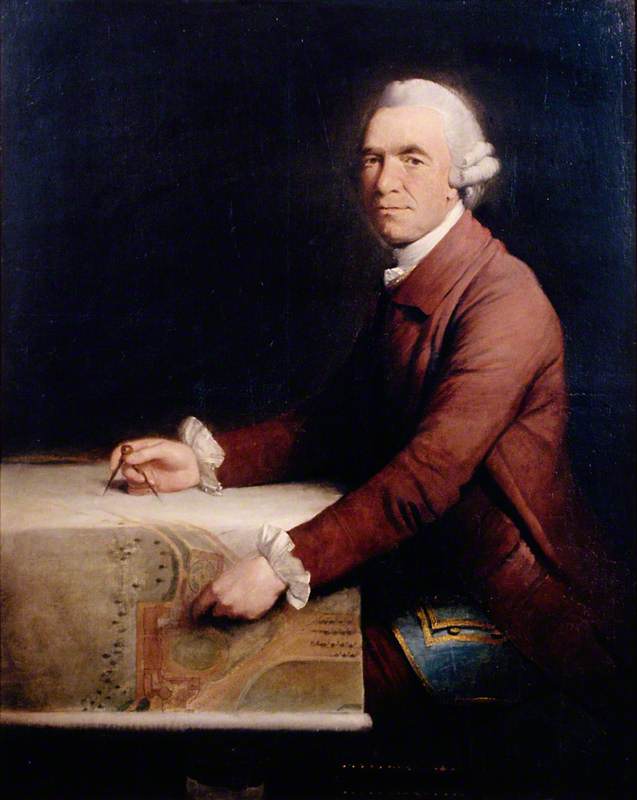

The architect Henry Flitcroft (1697–1769) commissioned portraits of himself and his wife, from Bartholomew Dandridge, to mark an important stage in his private and professional life. The portraits are not dated but must have been painted in 1742 or 1743 as the Flitcrofts' first surviving child, a son named Henry, was born in 1742. The portraits are clearly celebratory.

In the mid-1730s, Henry Flitcroft finally began to establish himself as an independent and fashionable architect. His first ever building was Bower House at Havering in Essex where his role with his collaborator, Charles Bridgeman, is proudly marked by a stone plaque, an unusual statement in a small private villa.

A View of the North Front of Bower House, Havering-atte-Bower

1791

Abraham Pether (1756–1812)

The house, completed in 1729, was commissioned by John Baynes who was lawyer to the Duke of Montagu. Flitcroft had already undertaken work for the duke and also, at nearby Boreham, for the banker Benjamin Hoare. He regularly worked for the Hoare and Montagu families for the rest of his life, designing Montagu House in Whitehall for the duke from 1731.

The Thames with Montagu House, from near Westminster Bridge, London

c.1749

Samuel Scott (c.1702–1772)

Flitcroft is often referred to as 'Burlington Harry', linking him, rightly and inextricably, to Lord Burlington. Richard Boyle, Earl of Burlington, was the wealthy champion of the style of architecture that derived from the Italian Renaissance architect Andreas Palladio who worked in Venice and its surroundings in the sixteenth century. Burlington was a generous patron and not only supported architects and designers but other artists in his circle at Burlington House, including the poet Alexander Pope and the composer Handel.

He took Flitcroft on immediately after his apprenticeship to produce elegant drawings and plans and to improve his master's own drawing style. Burlington paid for Flitcroft to travel, employed him at Chiswick House and opened the door to many other clients as well as securing him public posts.

Chiswick House, Middlesex

c.1742

George Lambert (c.1700–1765) and William Hogarth (1697–1764)

The nickname suggests that Flitcroft was not his 'own man'. However, the name was not used in Flitcroft's lifetime and, as soon as Flitcroft began to work for Montagu and Hoare, their recommendations also began to define and extend his career.

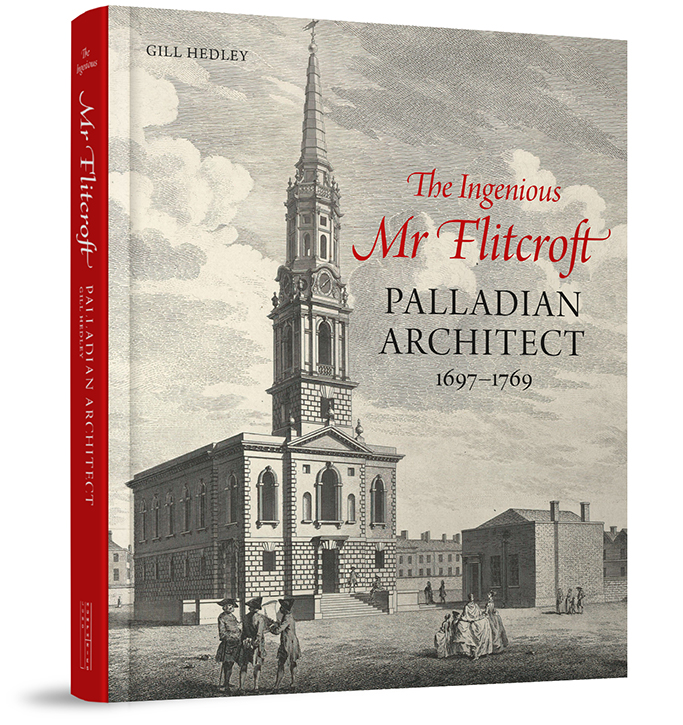

In 1732, Flitcroft's first major building, St Giles-in-the-Fields on the (then) very seedy edge of London's Covent Garden opened. Again, his name – 'H. FLITCROFT ARCHITECTUS' – is marked in stone. Quite soon he followed fashion in becoming a Freemason and was commemorated in a masonic handbook as 'The Ingenious Mr Flitcroft'.

The Ingenious Mr Flitcroft: Palladian Architect 1697–1769

2023, front cover of book by Gill Hedley, published by Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd

That is where the title for his new biography comes from and its cover shows not only an engraving of the new St Giles but, in the bottom-left corner, a trio of gentleman. These appear to be the artist, the engraver, and Flitcroft himself, plan in hand, gesturing towards his new building: another portrait of the architect.

His next major project was in Yorkshire at Wentworth Woodhouse, where he helped design the longest façade of any house in Europe, as well as its magnificent interior and several buildings in the landscape.

East Front of Wentworth Woodhouse, Yorkshire

1790, watercolour, pen & ink by R. Blasson

The most remarkable of these is the eccentric and stolid Hoober Stand, built to commemorate the English victory at Culloden.

The royal Duke of Cumberland had led the English troops but, in contrast to his reputation as 'Butcher' Cumberland, he was a patron of architecture, especially at Windsor. As a child, his architectural tutor was Henry Flitcroft and the duke later employed him to build a range of elements in the Windsor landscape, from the gothic Belvedere to a Chinese yacht.

So, in the early 1740s, Flitcroft was successfully launched into a busy and varied career. He had a paid position in the Office of the King's Works, distinguished and royal clients, and a church in the centre of London to his name.

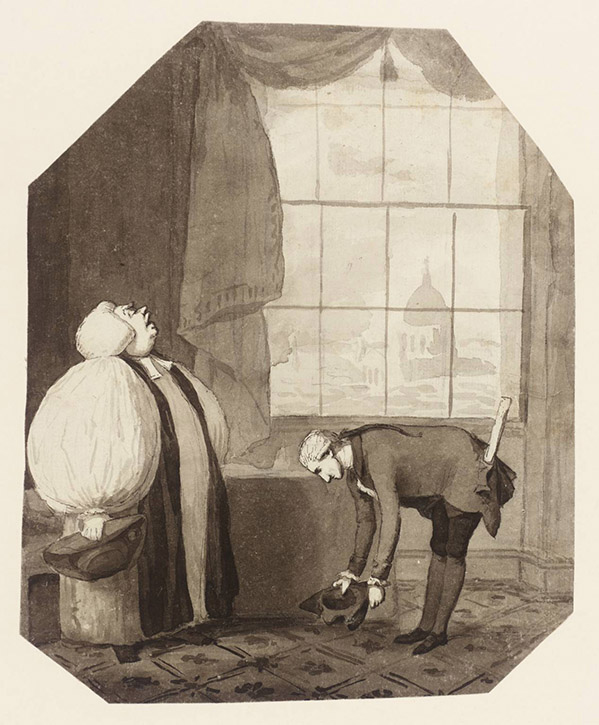

He took on his only apprentice, Kenton Couse (pronounced 'cows') who became a distinguished architect in his later career, designing the doorway and entrance to Number 10, Downing Street, where this portrait now hangs.

Kenton Couse (1721–1790), Architect

Mason Chamberlin the elder (1727–1787)

Flitcroft had speculated and developed property in London from an early age but, in 1741, he began to plan a country home in the airy and hilly village of Hampstead in north London.

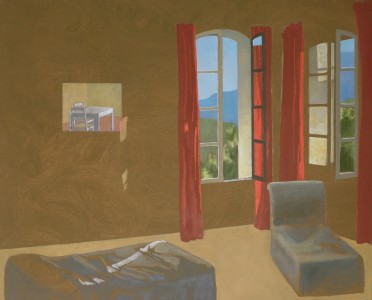

Frognal Grove, Garden Front, Showing Hampstead Parish Church

c.1820, lithograph by unknown artist

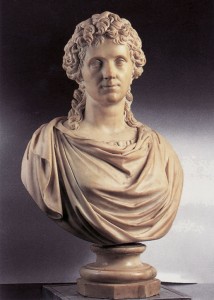

Sarah Flitcroft, who had married him in 1724, had given birth to twin daughters in 1740 but they did not live long. She became pregnant again in 1741 and Hampstead was planned as a healthy home for a new family. It worked, although Henry Flitcroft Junior was their only surviving child.

Bartholomew Dandridge's studio was conveniently near the house of Sarah Flitcroft's father, the master glazier Richard Minns, where Sarah probably spent much of her confinement. And more importantly, Dandridge had already painted the portraits of the Duke of Montagu, Lord Burlington, Handel and his fellow architects James Gibbs and William Kent.

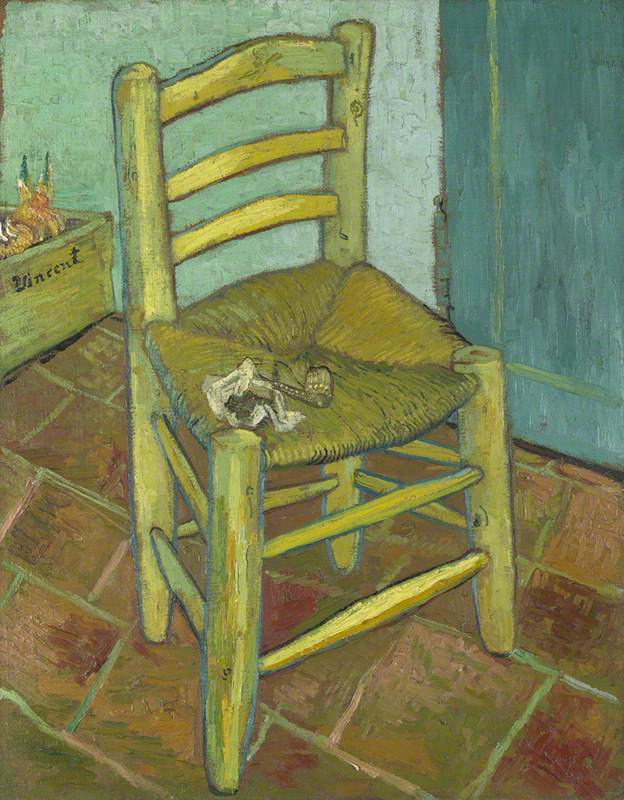

Flitcroft was already 45 and his wife was 37 but the portraits deliberately suggest youthfulness. The paintings have elaborately carved frames, almost certainly designed by Flitcroft himself.

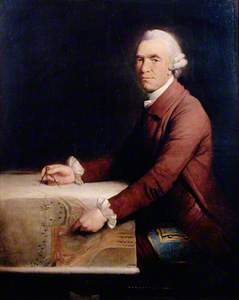

Henry Flitcroft (1697–1769)

c.1740

Bartholomew Dandridge (1691–c.1754) (attributed to)

Flitcroft poses with fingers turned outwards to display his folded wood and brass set square, compasses dangling from his other hand. He looks confident, open-faced and with a slight hint of determination and humour around the mouth. The set square and compass are symbols of Masonic tradition; equally, they are an architect's badge of office. In Masonic tradition, the square and compass symbols usually have the letter 'G' in their centre, referring to God. Or, to the 'Great Architect'. This could be a simple professional statement, a confident hint at Flitcroft's Masonry or, even, a sly private joke at his own status.

In the background of Sarah is a hazy view of the house Flitcroft built for them, known as Frognal Grove. She is shown in a natural pose and setting, holding two pink roses, in memory of their daughters. Her single pearl might recall their first son who also did not survive. A 'ewe lamb' stands in for baby Henry and it is possible that Flitcroft's lifelong problem with men of the church meant he wanted to avoid the overtly religious tones of a mother with a baby in her lap.

The determination revealed in his portrait and in newly discovered documents are at odds with his later reputation, which suggested him to be a mere follower. On Burlington's death, Palladianism became unfashionable. The profession of architect began to be formalised not least through the Royal Academy, founded the year Flitcroft died.

Flitcroft fought hard to maintain professional standards throughout his career. He battled with the Dean at Westminster Abbey, threatening to break a door down if he was not given the access he needed. At the end of his career, he was Surveyor of St Paul's where the Dean wrote of his 'obstinate perverseness' but where Flitcroft's 'Humble Petition' – which was anything but humble – guaranteed the status of the cathedral surveyor that still exists today.

Flitcroft's reputation dwindled to that of a competent, unremarkable assistant to Lord Burlington, but – if that was so – this raises the question: why did he have so many distinguished and loyal patrons over many decades? More importantly, why would Henry Hoare known, rightly as 'The Magnificent', have employed him as a collaborator at Stourhead in the 1760s?

Flitcroft designed some of the interior of the house and most of the buildings throughout the famously celebrated landscape. The Pantheon is his masterpiece.

It is obvious from new research that Flitcroft was careful with his clients' money, and his own, and spoke his mind, but was usually affable and diplomatic. He could turn his hand not only to pure Palladianism but to the Chinese and Gothic styles, to hydraulics, bridge-building and furniture. It is clear now why the Hoares, and many other landed families, were his patrons through several generations.

The Flitcroft line ended on Henry Junior's death. He was sadly incarcerated for 40 years after a mental breakdown. Sorting out the inheritance took further decades and court cases, ending a century after Flitcroft's own death.

Frognal Grove was eventually bequeathed via the family solicitor Thomas Street to his son, a fellow architect George Edmund Street, and was later subdivided. The stable block was altered by the modernist architects Alison and Peter Smithson for the sculptors Anthony Caro and Sheila Girling.

In a Flitcroft building, altered by the High Victorian architect G. E. Street, Caro created Early One Morning, in 1962, now in Tate's collection.

Gill Hedley, writer and curator

Gill Hedley's biography of Flitcroft, The Ingenious Mr Flitcroft: Palladian Architect 1697–1769, is published by Lund Humphries