Art UK has now revealed the real extent of the publicly owned fine Old Master collections in the United Kingdom in which artists such as Nicolas Poussin feature so strongly. Indeed, in the words of the first cataloguer, John Smith, in 1836 when discussing Poussin, 'it is difficult to avoid the language of the panegyric'.

In revealing works by major masters in places less well known to southerners, we can think of the Rubens in Scunthorpe, the Frans Hals in Hull and the Georges de la Tour in Stockton-on-Tees – all pictured above – but Poussin in Brighton?

The story goes back to my MA studies under Anthony Blunt at the Courtauld Institute in the years 1967–69. There was rather a lot of Poussin, especially as Blunt’s great book on the artist had just been published in 1966–67 in three volumes. Blunt could never tolerate anything slipshod and thus I emerged with a serious grounding in Poussin matters. In the years 1972–74 I was travelling to every public collection in the UK where Old Masters were to be found or might lurk. This was in preparation for my Old Master Paintings in Britain, published by Sotheby’s in 1976.

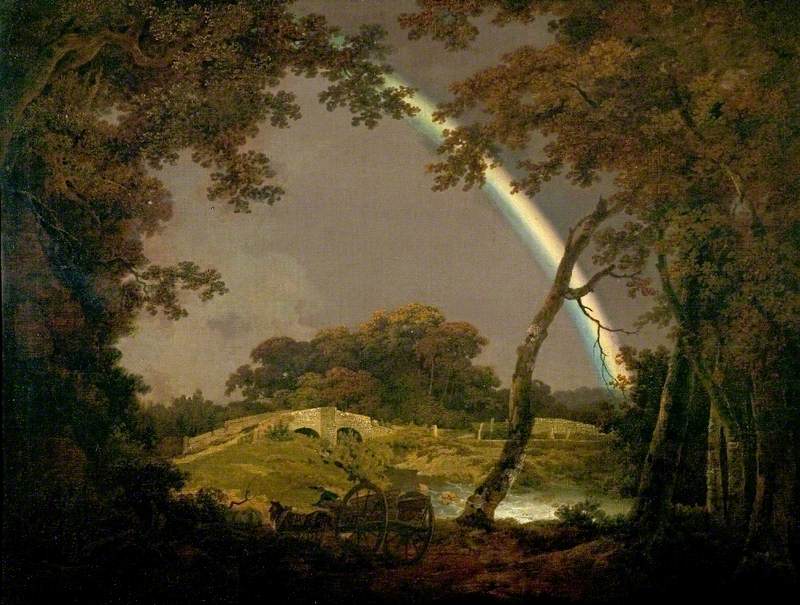

Thus by two circumstances, knowledge of Poussin and a methodical survey of collections, especially the smaller ones, I came across the Virgin and Child in a Garland of Flowers in Preston Manor, Brighton.

Image credit: Brighton and Hove Museums and Art Galleries

Virgin and Child in a Garland of Flowers 1625–1627

Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) and Daniel Seghers (1590–1661)

Brighton and Hove Museums and Art GalleriesIt bore the name Nicholas (sic) Poussin on the label and was later found to have part of the provenance recorded on the back. I was thus able to go to Blunt, not with trepidation, as the picture was listed in his Poussin book as lost. I approached him with a carefully chosen cliché, '...what a great and good thing it is that that which was lost now has been found'. Blunt replied with a wry smile, 'One normally visits Brighton for pastimes other than looking at art'. So the picture was added to the Poussin corpus and published by me in the Burlington Magazine.

Now that nearly 40 years have passed, the picture has entered the compendium of art historical literature. Indeed, on a recent visit to Brighton with a colleague, I was attempting to explain the picture’s complex history (too long to include here) and its position in Poussin’s early work. My peroration was interrupted by an enthusiastic attendant who informed me and my astonished companion that the picture had been discovered by none other than Anthony Blunt. My time had come.

Christopher Wright, Art UK advisor, art historian, artist and author of numerous catalogues of Old Master paintings in Britain