There are few artists more associated with a specific location than John Constable (1776–1837): parts of Suffolk are still promoted as Constable Country. So, it is a surprise to discover that he produced over 300 works around Salisbury Cathedral, nearly 200 miles away in Wiltshire.

One of these, an oil sketch of the cathedral, was due to be auctioned on 7th December 2021 with an estimate of £2–3 million, although ultimately it went unsold. Others, including the Tate's 1831 Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, are currently on show at the Royal Academy's 'Late Constable' exhibition, and yet more can be seen on Art UK.

Collectively these works illustrate the artist's stylistic development: he first visited Salisbury in 1811, the dates 11th and 12th September precisely recorded on a drawing in the Victoria and Albert Museum, and he continued to draw and paint the cathedral over six more visits until 1831.

The first examples are sunny, green-hued, blue-skied, crisply painted with sharp tonal contrasts, and the later images increasingly turbulent, grey-toned, loose and textured. If the oil on canvas sketch Salisbury Cathedral from the Close can be compared to the observed naturalism of Dedham Lock and Mill, then the Tate's rainbow picture reflects the full-blown Romantic drama of Hadleigh Castle.

The Salisbury pictures also show Constable's developing method. Throughout his career, he made on-site pencil and watercolour sketches as aides-memoire for later studio paintings: the 1811 visit to Salisbury yielded many such drawings from precise architectural draughtsmanship to rapid landscapes like this chalk View of Salisbury Cathedral from Old Sarum.

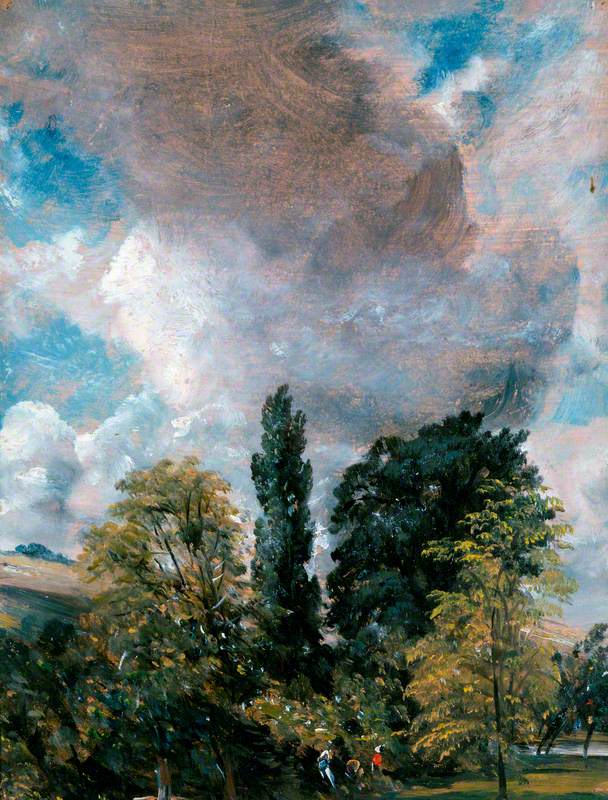

Increasingly, however, Constable painted outside in oils: The Close at Salisbury, in the Victoria and Albert Museum, is inscribed: ''Close' - 15 July - 1829 11. o clock noon - Wind S.W - very fine'. The rapidly sweeping, broad-brush swirls in the sky's dark centre emphasise dynamic immediacy, as Constable tried to capture scudding clouds, atmospheric translucency and diffused, fluctuating light, and heavier, unmixed dabs of colour evoke densely layered, wind-blown foliage.

Looking at these oil sketches, it is easy to see why he is often considered a proto-Impressionist – and although this was an experiment for his own use rather than a painting for public consumption, the deliberate placement of the three foreground figures, including that very characteristic dash of red, suggests that Constable was considering composition.

These small plein air images were then worked up in the studio, often into full-scale oil sketches. For Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows we have a quarter-size sketch (Tate) and a six-foot version (Guildhall Art Gallery) each with subtle compositional shifts (note the position of the dog), neither with rainbow.

Salisbury Cathedral, Wiltshire, from the Meadows

1829–1831

John Constable (1776–1837)

It is in these sketches that Constable's vibrancy is fully revealed: every inch of the canvas is alive with texture and restless, agitated brushwork, flashes of reds and repeated whites zing out; you can almost hear the wind in the trees. They show an artist walking a tightrope between his own desire for expressive naturalism and Academy demands for control and finish.

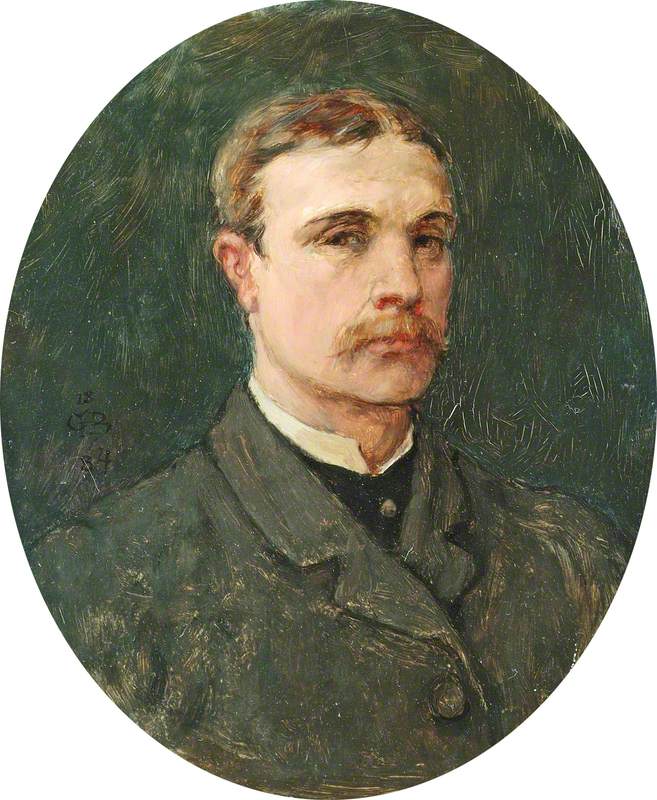

As well as their aesthetic interest, the Salisbury paintings offer a biographical insight into Constable's life. He made the journeys to Wiltshire out of a deep friendship with two John Fishers: the elder was a keen amateur watercolourist who had been rector at Langham in Suffolk, before becoming Bishop of Salisbury, and the younger, his nephew, acted as archdeacon at the cathedral.

The younger John Fisher painted by Constable in 1816, officiated at Constable's marriage in London that year, hosted the honeymoon, and later invited him back to Salisbury to seek solace after his wife's death in 1828.

Both men were significant patrons, and many of the Salisbury works were commissioned by them, notably Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Grounds (1823), which includes Bishop Fisher and his wife foreground left, and led to two other almost identical paintings, including one (held in The Huntington Museum in California) produced for Fisher's daughter with a stipulation that Constable 'put a little sunshine' into the dark clouds.

The Salisbury pictures also reveal the depth of Constable's faith. He was a sincerely religious Anglican who must have felt the full spiritual weight of Salisbury's Gothic magnificence, with its spire, the tallest in England, seeming to pierce heaven itself. Churches appear in many of his East Anglian works, usually small background features (for instance centre back in Dedham Lock and Mill), almost as if they are too much a part of life to need emphasis. But Salisbury takes centre stage.

In Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Grounds, it is given a proscenium arch of trees, which is itself mirrored by the dark arch of cloud directly above the spire. The actors, human and animal, create foreground interest but the cathedral is the real star of the show, rectilinear and man-made against the natural surroundings and yet, with the fleshy, pinkish hue of the stone and curving complexity of Gothic architectural detail, alive and organic.

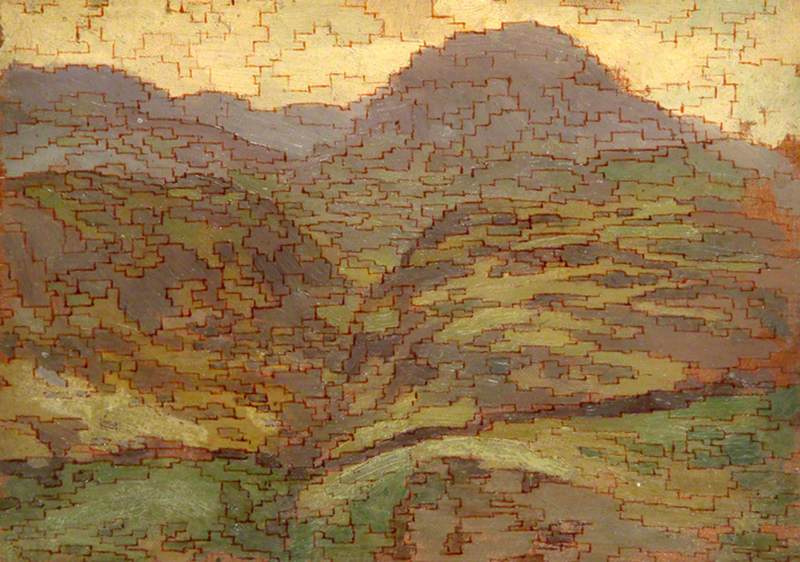

The link between Gothic architecture and nature was not unique to Constable. It was stock in trade for artists exploiting the Picturesque, a style theorised by William Gilpin in Observations Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty (1786) which promoted the sentimental appeal of rough, irregular and aged scenery.

Part of the Ruins of Tintern Abbey

1834 or before

Thomas Creswick (1811–1869)

Thomas Creswick's Part of the Ruins of Tintern Abbey, which shows a crumbling Gothic structure succumbing to time and nature, and Charles Towne's Landscape with Bolton Abbey, where the liveliness of the foreground only serves to highlight the poignant ruined past in the distance, exemplify the Picturesque use of Gothic forms as a prop which 'has suffered from the hand of time' devoid of any real spiritual meaning.

Constable had flirted with the Picturesque in his youth, making a sketching trip to the Peak District in 1801. However, what makes his Salisbury pictures so striking is that religion is thriving: the cathedral is not ruined, not swallowed up by nature, not softened by distance and atmospheric perspective.

In fact, they go further, creating a symbiotic relationship between Church and nature in which, as in the 1820 sketch Salisbury Cathedral and Leadenhall from the River Avon, the cathedral seems to grow out of the ground and trees become living spires, a testament to the vitality of the Church and the artist's faith.

Salisbury Cathedral and Leadenhall from the River Avon

1820

John Constable (1776–1837)

The great 1831 image exemplifies this. Here the compositional arch of Gothic vaulted trees in Bishop's Grounds has become a symbolic one, the rainbow of God's covenant with Noah. The watery foreground provides another reminder of the Flood and the spike of lightning above the cathedral roof is an image of almighty power. The cross which tops the spire, almost swallowed up in cloud in the earlier image, here seems to spear through the darkness, pushing it aside.

It has become something of a cliche to ascribe the emotionally wrought brushwork and chilly tones of the late paintings to Constable's state of mind following his wife's death. Certainly, intimations of mortality abound in the crumbling ruins of Hadleigh Castle with storm-tossed sky and threatening crows, but the mood here is more complex.

The 'crock of gold' where the rainbow touches earth is John Fisher's home and the whole image is suffused with the message of hope which the rainbow represents. The tangled woodland of the left gives way to clear, open fields; the ancient anthropomorphic tree on the right is sprouting anew; the horses enter the water knowing they can reach the other side; the birds are not portents of doom but swallows, reminders of spring and renewal.

In the early nineteenth century, Gothic architecture was increasingly linked to national identity. Gilpin had promoted the idea that English Gothic 'may be called a peculiar feature of the English landscape' which was 'unrivalled among foreign nations', and although more scholarly studies established the style's French origins, there was a consensus that English Gothic surpassed the European.

It embodied the nation's medieval past, traditions of parliamentary democracy and the established Church, associations which were to become increasingly important over the course of the century. Thus, long before Charles Barry and Augustus Pugin undertook the rebuilding of the Houses of Parliament after 1836, James Wyatt had 'gothicised' the old House of Lords in 1808.

Constable himself had a strong sense of national pride, writing to Fisher in 1823: 'I was born to paint a happier land, my own dear England', and going on to quote from Wordsworth's 'Thanksgiving Ode, January 18, 1816', which celebrated the end of the Napoleonic Wars. In Constable's Salisbury pictures, therefore, the most English of artists paints the most English architecture in the most English countryside.

Arguably this close association between Church, nation and countryside defines Constable as a profoundly conservative artist. Fisher's initial suggestion of 'Church under a Cloud' as a title for Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, has led to the painting being seen as a political commentary on fears over the 1829 Catholic Emancipation Act, electoral reform and rural change. It can be read as a constructed synthesis of nostalgia: a very East Anglian foreground with a cart reminiscent of The Haywain and a dog from The Cornfield, melded with Constable's go-to symbol of religion, under impossible meteorology and a mythical rainbow.

Constable saw it as an apotheosis: 'the full impression of the compass of my art'. But whether it is symbolic or naturalistic, political or religious, it is, like all Constable's landscapes, optimistic, personal and deeply felt. He called his pictures 'his children': he painted places for which he had 'over-weening affection'. For him, famously, 'painting [was] but another word for feeling'. The Salisbury paintings are about the strength of faith, friendship and belonging. It really was Constable's cathedral.

Catriona Miller, art historian and freelance writer

Further reading

Graham Reynolds, Constable's England, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1983

Michael Rosenthal, Constable, the Painter and his Landscape, Yale, 1983

Timothy Wilcox, Constable and Salisbury: The Soul of Landscape, exhibition catalogue, Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum, 2011