In 1765, the Italian-born painter Agostino Brunias (c.1730–1796) arrived in the West Indies having travelled on the ship of the sugar plantation owner and Governor of Dominica, Sir William Young.

By establishing himself as a 'colonial painter' in the tropical archipelago of the Caribbean in the 1770s, Brunias romanticised the slave labour and leisurely activities of a multicultural, creolised society under the British Empire. Yet he also painted black and mixed-race subjects with a kind of dignity and reverence rarely seen before in European art history.

So how did Brunias' rose-tinted paintings of life on British sugar plantations come into existence? And how should we frame, analyse and judge them in today's context?

Born in Rome in around 1730, Brunias studied at the Accademia di San Luca before moving to England in 1758 under the employment of the Scottish Neoclassical architect Robert Adam. Departing London in 1770 as the personal painter to Sir William Young, Brunias worked and voyaged between the British-controlled Caribbean islands until his death in 1796 (although records show that he returned to England for some time in 1773).

A historically conflicted territory, many islands of the Caribbean came under British rule after they defeated the French during the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). One of the islands ceded to the British was Dominica, where Brunias spent most of his time. Situated in the Lesser Antilles, between Guadeloupe and Martinique, at least 70,000 enslaved Africans were working on the small island by 1773, meaning the population was predominantly black. The free people of colour often painted by Brunias were usually individuals of French and African heritage, many of whom achieved wealth and power.

Brunias' patron Sir William was not only the Governor of the island, but also the President of the Commission for the Sale of Lands in Dominica, Saint Vincent, Grenada and Tobago. This meant he oversaw the sale of colonial land to British investors – an attempt to expand the business of slavery and sugarcane.

A patron of the arts, Young had previously commissioned the German-born artist Johann Zoffany to paint his large family a few years before he sailed across the Atlantic with Brunias. A symbol of his status, wealth and career, a black servant boy can be detected in the left-hand side of the painting, helping one of his sons to mount a horse.

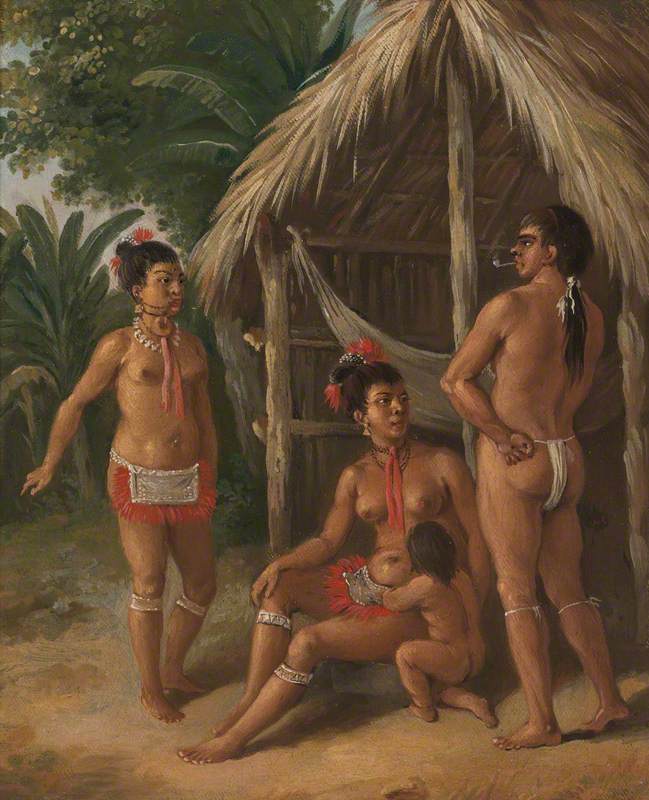

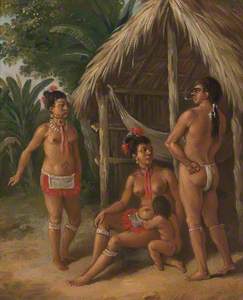

Free West Indian Creoles in Elegant Dress

c.1780

Agostino Brunias (c.1730–1796)

The move to the West Indies with Young was a strategic career decision for Brunias. Not only did he receive the lucrative commissions of other wealthy patrons, but he encountered less artistic competition, and established himself as one of the few artists to paint the recently acquired British territory.

By depicting an entirely new geographical setting unknown to British audiences, Brunias tapped into the nation's projected fantasies of the 'exotic', while portraying the West Indies as a (largely fictionalised) tropical, harmonious land of abundance and prosperity.

Unlike his contemporaries, Brunias gave an image to the 'mulattos', meaning the mixed-race descendants of both white and black heritage. A historical classification dating back to the sixteenth century, the term is now considered derogatory.

A West Indian Flower Girl and Two Other Free Women of Color

c.1769

Agostino Brunias (c.1730–1796)

Just as Brunias had once painted picturesque Italianate scenes for wealthy British tourists on the Grand Tour in Italy (when wealthy, young aristocrats voyaged through Europe), he conjured up romanticised visions of an idyllic, exotic, colonial life in the West Indies for his prospective buyers living in or travelling through its islands.

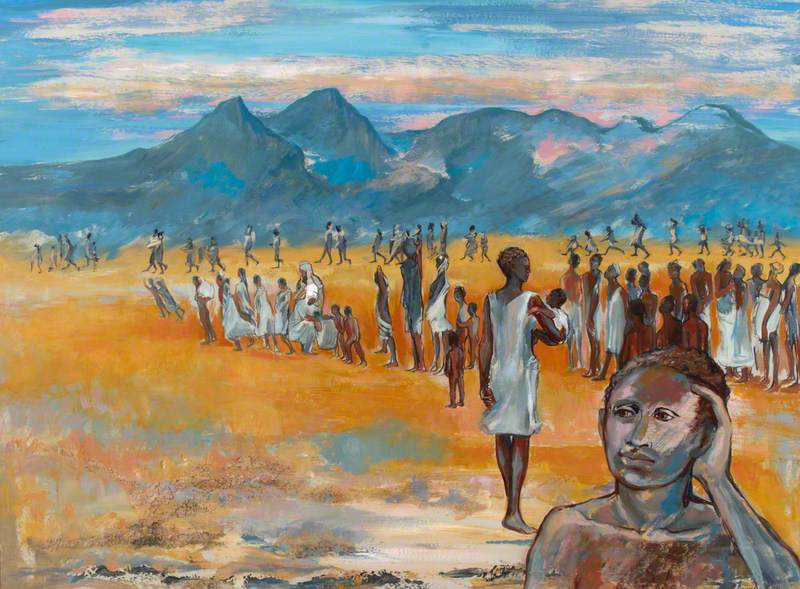

Aesthetically pleasing, yet not without political intent, Brunias' paintings served as a form of propaganda. Promoting Young's imperialist mission, he promoted the West Indies as a 'thriving colonial economy', a place of opportunity where the generations of deported African peoples were not resisting their enslavement.

Rather than presenting an objective reality – he painted in the tradition of 'vérité éthnographique' (meaning 'ethnographic truth') – his works omitted the violent realities, punishment and discipline of enslaved labour. Instead, Brunias captured diverse and joyous social gatherings of slaves, freed people of colour and colonisers, mirroring images of the refinement and respectability found in Europe.

Such an idyllic image met the aesthetic tastes and demands of his wealthy colonial patrons, who relied upon positive pro-slavery images of the Empire to quell abolitionist sentiment, not to mention to safeguard their own careers (which were dependent upon the profitability of slavery).

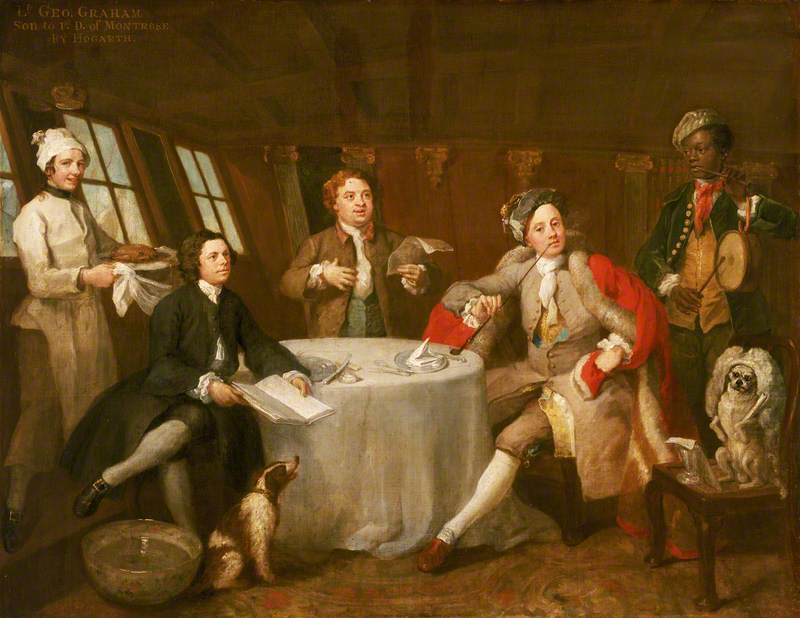

Captain Lord George Graham (1715–1747), in His Cabin

c.1745

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

His work bears striking similarities to the popular genre of the 'conversation piece', a kind of informal type of group portraiture created by English artists like William Hogarth and Thomas Gainsborough. Yet in his 'colonial' conversation pieces, people of colour feature prominently. Unlike the paintings of Hogarth, black figures are not simply pushed to the peripheries of paintings to represent the maid, servant or footman. Radically, Brunias portrayed autonomous, self-possessing, refined individuals wearing the same European clothing as their white counterparts.

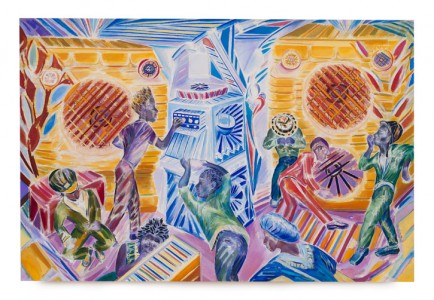

In Dancing Scene in the West Indies, a group of females is shown dancing in an open area. They move carefreely in dresses that appear to be a hybrid mix of both African and European styles (turbans, headwraps, corsets and shirts).

Planter and His Wife, with a Servant

c.1780

Agostino Brunias (c.1730–1796)

Brunias' oeuvre presented the idea of 'benevolent' slave ownership, mirroring the attitude and behaviour of his patron.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Enlightenment reforms were aiming to 'ameliorate' the conditions of slave labour in the West Indian colonies. As a result, slave populations in the Caribbean were encouraged to reproduce and multiply, so that future generations of slave labour would be available if and when the Atlantic slave trade came to an end (which it did in 1807). This economic strategy was something Sir William Young was asked to oversee.

According to art historian Sarah Thomas, such benevolent views grounded in new waves of Enlightenment thought were not because of humanitarian or moral motives but were to ensure the longevity of slavery as an economic system.

However, other readings of Brunias' work argue that he didn't merely communicate the colonial anxieties of his patrons. Rather he deliberately called into question eighteenth-century racial classifications. In a neutral – or even celebratory – manner, his paintings revealed the emergence of a 'Creole' culture, (a term referring to the mixing of white European and black populations). In an unprecedented fashion, Brunias painted all of his subjects with equal reverence, dignity and agency.

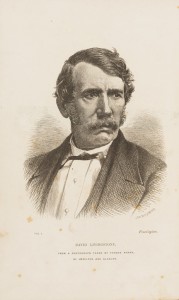

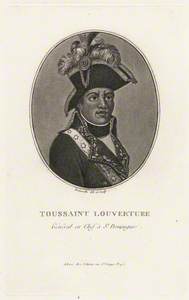

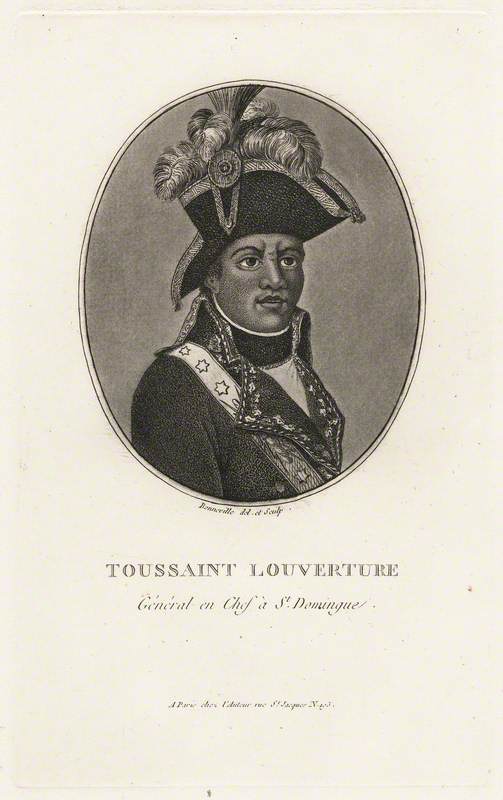

Toussaint L'Ouverture

(after an earlier work by an unknown artist) early 19th C

François Bonneville (active 1787–1802)

The subversive power of Brunias' paintings has even been attributed to the Haitian slave rebellion and revolution of 1791, in which a former slave named Toussaint L'Ouverture liberated enslaved peoples from French colonial rule. Through the dissemination of reproduced prints, Brunias' work ended up in Haiti where his images of a racially mixed society became popular among Louverture's supporters and a 'call to arms'.

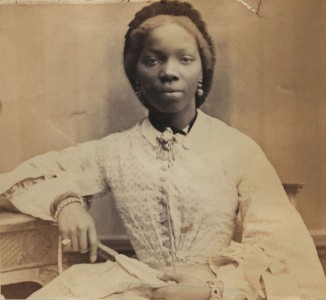

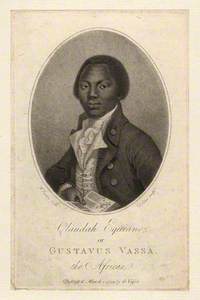

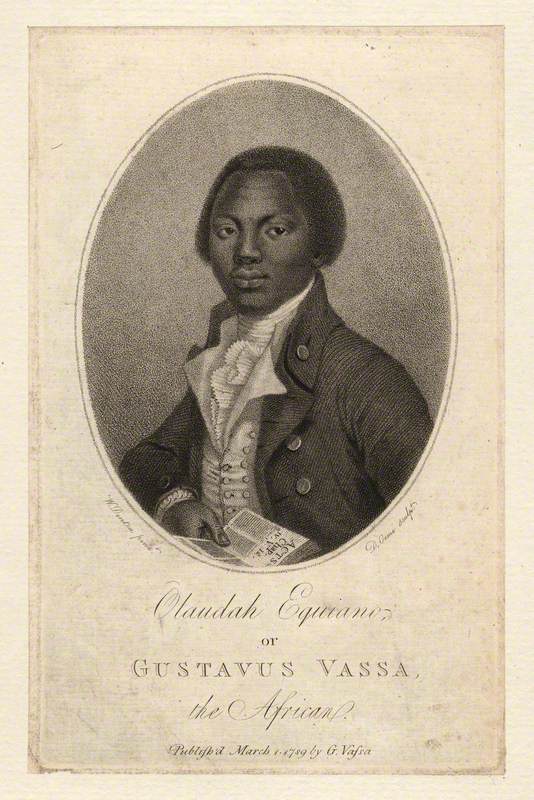

Olaudah Equiano ('Gustavus Vassa')

(after W. Denton) published 1789

Daniel Orme (c.1766–c.1832)

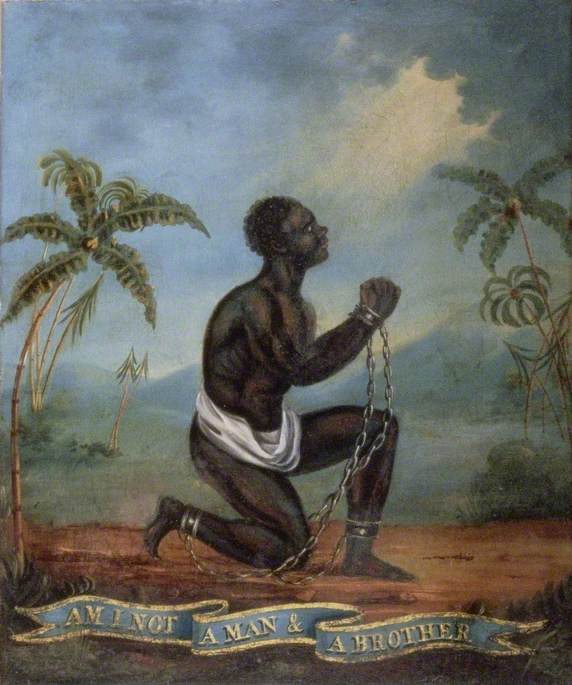

On the other hand, Brunias' paintings of colonial labour undermined the messages of abolitionist campaigners back in England, where the rise of anti-slavery activism had gained in popularity.

The former slave Olaudah Equiano ('Gustavus Vassa') had become a bestselling author after publishing his important autobiography in 1789 that detailed the grim everyday realities of life as a slave and working on Caribbean plantations. The book chronicled his journey from a free man to a slave, describing his brutal torture and the inhumanity of slavery, particularly in the West Indies. Equiano painted a very different picture to the one fabricated by Brunias.

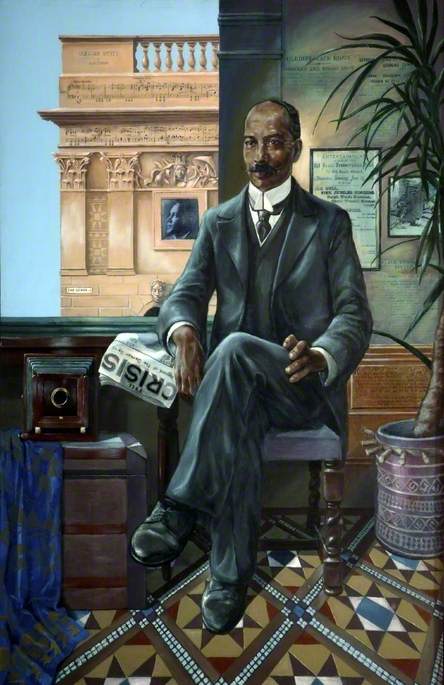

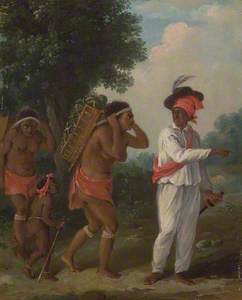

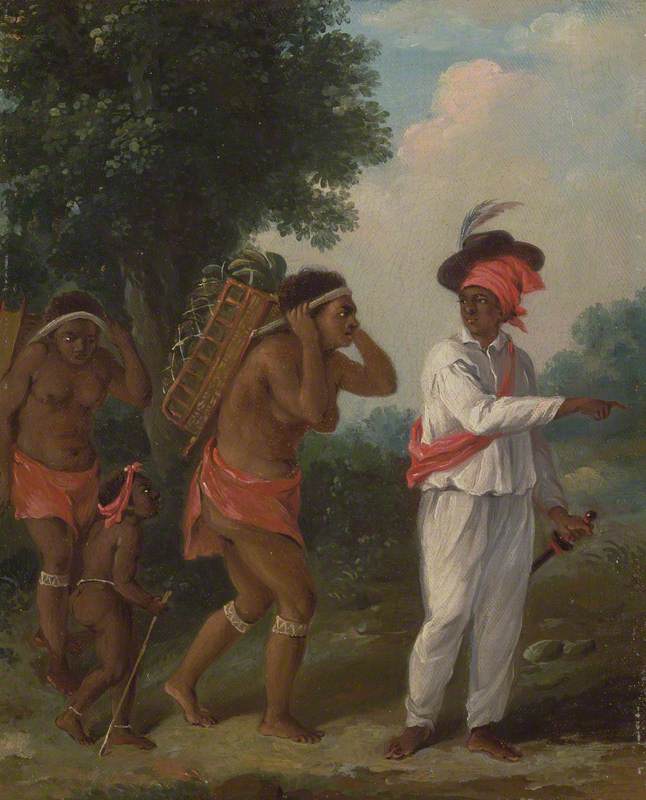

West Indian Man of Color, Directing Two Carib Women with a Child

c.1780

Agostino Brunias (c.1730–1796)

So was Brunias straightforwardly a colonial or 'plantocratic' painter? Or was he, in fact, slyly subverting the colonial script and projecting a dignified and empowering image of mixed-race, black and indigenous communities?

Although he began his career in the West Indies as a painter for the colonial elite, his works assumed a political role throughout the Caribbean – a radical, hypothetical representation of a free, anti-slavery society.

While we may question the intention of his intriguing depictions, Brunias' work helps us to investigate the realities of colonialist history and the imperialist ideologies underpinning the rise of Britain as a world power in the eighteenth century.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK