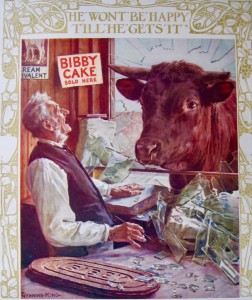

Portraits of horses and their riders are ubiquitous throughout British history. The early twentieth-century painter Sir Alfred Munnings (1878–1959) was particularly moved by the figures of horses and female equestrians.

In the first book of his three-volume autobiography An Artist’s Life, Munnings tells us, 'Grey horses were always my delight; my imagination stirred at the sight of them… She remains the same spirited creature in my mind now as she appeared to me long ago. Clean-curved, nervous ears, a long neck, black legs and hard tendons with a white hind leg'.

Horses and painting

Norwich School of Art was where Munnings first started to study the bodies of horses. There, he carefully copied horses from sculptures, such as the antique Parthenon horse head, and studied the organisation of their bones through drawing. This traditional art school training sharpened his eye for transforming the anatomy and proportions of real, moving horses into a two-dimensional form on the page.

As Munnings’ specialisation in drawing and painting horses was informed by spending a lot of time with horses in the flesh, his critics argued that he was more interested in the horses than in painting. But without this real experience, mostly gained in rural Norfolk and Suffolk, Munnings’ openair equine and equestrian paintings would not capture horses’ characteristics with such a hyper-sensitive quality.

The Grey Pony, Augereau, in a Sandpit with Groom, George Curzon

1905

Alfred James Munnings (1878–1959)

Regardless of what his critics said, the effect Munnings’ horse paintings had on their viewers shows that he was, of course, just as interested in painting as in horses. But what about his interest in other people? Originally, The Grey Pony (above) only showed a white horse. In 1953, at the age of 75, Munnings added 'George', the horse’s groom, into the picture.

The painterly harmony between the horse’s brightly coloured coat, the yellow of the flowers in the grass and the green jacket of his groom gives us a sense of how Munnings perceived the relationship between humans and horses. This painting shows the translation of a calm, ephemeral moment onto canvas – the artist having looked back in time.

Painting and women

When Munnings met Florence Carter Wood, who studied painting at Stanhope Forbes Art School, he started to devote more time to painting women on the back of grey horses. Then, about half a year before her father gave consent to their marriage, Munnings made Two Lady Riders under an Evening Sky. The painting is believed to be a double portrait of Florence.

In this work, he portrayed his lover galloping away from him, riding sidesaddle as was fashionable at the time. He depicted her at a three-dimensional angle that allowed him to observe her back, as well as the profile of her body twice; this also provided room for the path that lay in front and her galloping bay and grey horses. In blending her white and pink costumes with the rosé sky and the freshly blossoming grass, Munnings expressed his romanticised view of her.

Not even two years into their marriage, Munnings travelled to Dublin with the money he made from selling his work at the Leicester Galleries in London to buy himself a new grey model horse. As the experienced horse dealer Mr John Milady helped him to buy a grey mare for only 33 guineas, he was also able to afford a male bay horse. The horse he bought is believed to be My Grey Mare, and is strikingly similar – in the colour composition, the shape of the legs, and the neck and body proportions – to the grey mare under the saddle of his wife. It appears as if he even captured the head of his riderless new grey mare in the same position: blinking and drifting slightly left and forward.

Munnings’ life as a horse painter meant that he either travelled to present his work to galleries all over the country, or painted horses in the countryside. Florence was therefore mostly left to her own riding and painting in Lamorna, where the couple lived together. Then on 24 January 1914, a few months before the First World War broke out, his wife poisoned herself.

Once more, a grey horse and a woman

Munnings does not mention his relationship with Florence once in his autobiography. Instead, he devotes all of his writing to his second wife Violet McBride, another highly skilled horsewoman, who he met at the Richmond Horse Show in 1919. When he first asked her to sit for him, she refused. Then, a year after she had agreed to be painted by him, they married and started to spend time at racetracks together.

Lady Munnings Riding a Grey Hunter ('Magnolia') Side-Saddle, with Her Dogs on Exmoor

1924

Alfred James Munnings (1878–1959)

In 1924, he painted Lady Munnings – also on a grey hunter. After making at least three studies of Violet on a grey horse, his final painting shows her sitting upright, looking straight ahead, with her gloved left hand held deeply in the pocket of her tweed jacket. With the reins and whip in her right hand, she sets the path for her horse and dogs.

Despite Munnings’ return to painting a grey horse, this equestrian portrait is different to the ones discussed before, as Lady Munnings’ horse nervously chews his bridle bit, turns his neck to the right and creates a tension between his mouth and her right hand. Through this painting it becomes clear that the artist’s informal approach to painting horses and people had started to mutate into a self portrait of his marriage within high society.

In contrast to his double portrait of Florence, this later equestrian portrait is much more refined in terms of style and colour composition. But it seems to lack the romantic essence which makes his early paintings so compelling. Instead of galloping onwards, as he depicted Florence, the more matured Sir Munnings paints Violet stiffly striding past him while facing determinedly forward.

My Wife, My Horse and Myself

exhibited 1935

Alfred James Munnings (1878–1959)

About ten years later, Munnings painted Violet again. My Wife, My Horse and Myself depicts her in the moment of performing a walk on their French-bred horse named Anarchist in front of himself and the facade of their home. This horse– in comparison to his previous ponies, racehorses, and hunters – was schooled by a rider who was trained in the disciplining art of classical dressage at the Cadre Noir of Saumur.

The clean lines of each single figure seem to make up the character of the work, while the yellow tone of this painting appears to work against this as it unifies and smoothens the subject matter of this society portrait.

In an earlier painting of his wife, In Cornwall from 1921, Munnings’ focus is different. It shows Violet sitting on a grey horse in a relaxed posture and dressed in a léger style, which is echoed in the behaviour of the grey horse as it grazes contentedly with her on its tensionless back.

In Cornwall (Portrait of the Artist's Wife)

c.1911–1921

Alfred James Munnings (1878–1959)

We can learn a lot about early twentieth-century horse painting by engaging with Munnings’ body of equestrian paintings. But equally, we can see that his devotion to painting and, in particular, grey horses was not so different to the relationship he had with women.

Lisa Moravec, PhD candidate at Royal Holloway (Drama, Theatre and Performance, focus on multispecies relationships and bodily movements), bilingual writer and part-time arts teacher at Kingston University.