For those in the know, the very name Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) evokes the fey delicacy of his most familiar works. Associated with a type of painting known as the fête galante – scenes of wealthy, well-dressed types socialising in benign parkland – he was, according to the scant biographical information we have, unhappy with his work. His friend, the Comte de Caylus, described Watteau as a thoughtful and well-read man who was 'continually sickened by what he was doing'.

Fête galante: Conversation Piece

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Caylus himself regretted that Watteau was not an artist of history and action. Instead, he became a painter of contemporary inaction. His subject is indolence and self-indulgence, which appear all the more culpable because we know the French Revolution was just around the corner.

But Watteau's art is not what it seems. The scholar Norman Bryson likens Watteau to Mozart, as artists who were 'mistaken for rococo frivolity'. Ultimately, as we look more, 'we begin to see the darkness'.

Watteau was born in the Flemish town of Valenciennes in 1684. He moved to Paris in 1702 and may have spent a short time working as a theatrical scene painter. He was greatly inspired by the theatre, and his painting Fêtes Vénitiennes (1718–1719) takes its title from a successful opera-ballet of the same name by André Campra. The opera's plot involves disguise and deception, intrigue and affairs of the heart.

Although Watteau's painting does not represent a scene from the opera-ballet, it may depict a dance from Campra's drama. And there appears to be some significance in the identity of the three main figures – a love triangle perhaps.

Watteau could be a morose and prickly character, but Caylus notes a spirited, less guarded side to his personality: a man with a 'taste for love'. He enjoyed the company of the men with whom he shared lodgings, including Caylus, who describes how 'free from all importunities, [Watteau] and I, together with a third friend impelled by the same tastes, experienced the joys of youth combined with the vivid pleasures of the imagination...'

That third friend might well have been Nicolas Vleughels, a fellow artist of Flemish descent – he makes an appearance in Les Charmes de la vie (c.1718–1719), dressed in red and leaning against a chair.

Watteau and Vleughels are both depicted in Fêtes Vénitiennes – Vleughels as a turbaned bey from the east and Watteau as a humble bagpipe player. A female figure is also in two guises – clothed and unclothed – as the shimmering central subject, at once courtly and elegant, and then (or so we might fantasise) reclining naked on the strange plinth of a waterfall.

Fêtes Vénitiennes (detail)

1718–1719, oil on canvas by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1648–1721)

This seductive figure is implausible as a piece of parkland statuary. She is, in fact, a living figure made to look like stone, her nakedness only permissible among the clothed figures by virtue of being a pseudo-statue. She may be seen as an early prototype for Édouard Manet's scandalous nude among clothed men in his 1863 painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe. Her seductive pose also finds its like in several works by Henri Matisse.

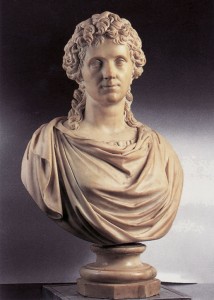

The figure is one of a number of arresting statues of women in Watteau's art. In Fête Galante in a Wooded Landscape (c.1719–1721), an ample Rubensian woman also occupies a plinth on the right side of the picture.

Fête galante in a Wooded Landscape

c.1719–1721

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Her highly naturalistic pose suggests a living figure. Her generous physique is unusual for Watteau, whose people, his women in particular, are more often delicate and slight. The impression we have is of an interloper, a Baroque migrant who has crashed the party, unnoticed except, surely, by the caped gentleman below her.

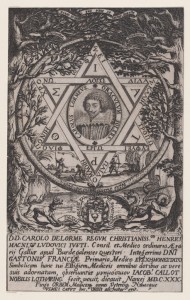

In the 1732 engraving of Fêtes Vénitiennes, made by Laurent Cars after Watteau's painting, Vleughels is engaged in a courtly dance with the central beauty, thought to be an actress called Charlotte Desmares. The music is provided by Watteau in humble dress, as the piper. Watteau is an artist of glances, and here we find a crossfire of looks and speculate as to the latent emotions.

Fêtes Vénitiennes

1732, engraving after Jean-Antoine Watteau by Laurent Cars (1699–1771)

The actress looks at Vleughels, Vleughels stares past her at Watteau, Watteau stares rather dreamily into space (or perhaps at Vleughels). Yet Watteau is himself the object of a stare: above him the statue looks down flirtatiously at him, and she is pointed at by the caped, important-looking man at the back. He, in turn, looks at Vleughels.

The easy assumption is that both friends were enamoured of the beautiful Charlotte, but that Watteau has lost out. Even though he plays the bagpipes – a well-known symbol of male genitalia – he is no match for the more worldly and assertive Vleughels. Watteau is relegated to the lowly position of musician, cruelly providing the tune to which his friend engages with the beauty. His clothes also identify him as a person of a lower class.

The painting may be, as Posner suggests, 'a kind of risqué, private joke' between the two friends, but it could be that courtly manners are also the target: the hypocrisy of what Calvin Seerveld calls the 'sweetness and light, ravishing modesty, endless fantasy and schooled elegance' of polite society.

Watteau's genre of fête galante painting is notable for its absence of story and action. Its cast of characters have a determined listlessness. The most marked sign of movement is the strumming hand of a guitar or the wafting of a fan. Although dance features in some paintings, we witness no great flurry of action, but a poised moment that might be mistaken for stillness, as in Fêtes Vénitiennes.

Perhaps because Watteau's theme is to be found in his human subjects, the landscapes which they populate are little more than generic, lifeless backdrops. The French painter Eugène Delacroix, no great fan of Watteau's, described his trees as 'done according to a formula... they remind one of theatre décor rather than trees in a forest'. Delacroix is quite right. His cast of characters care nothing for their verdant world and their expressions betray boredom or indifference.

The dreamy nature of Watteau's fêtes galantes encourages the viewer's eye to roam from figure to figure, across intangible landscapes, memorably described by curator Aaron Wile (with reference to Watteau's L'embarquement pour Cythère from 1717) as 'a vaporous nowhere of water and mountains and sky'.

Fêtes Vénitiennes (detail)

1718–1719, oil on canvas by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Fêtes Vénitiennes is notable among Watteau's works in its depiction of a tense, if mute, drama played out between significant characters. The eye moves between the protagonists, weaving a tale of sex or romance. And Watteau himself, as the piper, wears the distracted look of the dreamer. But that forlorn gaze has another reading: Watteau is not only lovesick, but in the grip of a real illness, tuberculosis, from which he would die just two years later.

Some think that it is his illness that gives his pictures their sadness and gravity. 'Watteau, permanently dying, tries to draw vitality from his figures by osmosis,' writes Norman Bryson, who identifies the artist with his many sad fools – and the famous Gilles. Watteau the clown – and by extension, the self-portrait in Fêtes Vénitiennes – 'is sad because nature has disqualified him from love'.

Pierrot, Harlequin and Scapin

c.1719

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Watteau's reluctance to depict narrative gives his works their quality of staged aimlessness. They can be viewed as minimalist – even absurdist – theatre pieces. As portrayals of the idleness of the well-to-do, they may irk the modern spectator, but they have a more fundamental purpose than that: Watteau is uncovering an existential emptiness.

The fancy clothes came from a dressing-up box – they clothe people who face the same hard truth as the rest of us. That life is self-absorption distracted by intrigue. As the critic Christopher Allen writes, 'in Watteau's world we are only ourselves by virtue of the play or dance or song in which we take part, and when the music stops, we are at a loss'.

Despite the satins and silks and lovelorn glances – and all the trappings of the ancien régime – it is the modernity of Watteau which is often asserted, both in his temperament and his art. For the writers Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, he 'personifies the modern artist in the finest and most disinterested sense of the word, the modern artist with his search for the ideal, his contempt for money, his lack of care for the morrow, his unplanned life.' His art relies on nothing more than its own self-contained craft, its disregard for the bold gesture and the dramatic narrative.

As critic Paul Duro puts it: 'Without Watteau there could have been no Boucher, Fragonard, or Chardin. Without him there could have been no Manet.' Quite simply, as Duro claims, 'modern art begins with Watteau'.

Adam Wattam, writer

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Christopher Allen, French Painting in the Golden Age, Thames and Hudson, 2003

Anita Brookner, Watteau, Paul Hamlyn, 1967

Norman Bryson, Word and Image: French Painting of the Ancien Régime, Cambridge University Press, 1994

Anne-Claude-Philippe de Tubières, Comte de Caylus, 'The Life of Antoine Watteau' in Art in Theory 1648–1815, Wiley-Blackwell, 2001

Paul Duro, The Academy and the Limits of Painting in Seventeenth-Century France, Cambridge University Press, 1997

Michael Levey, Rococo to Revolution, Thames and Hudson, 1995

Donald Posner, Antoine Watteau, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1984

Calvin Seerveld, 'Telltale statues in Watteau's painting' in Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 14, no. 2 (Winter, 1980–1981)

Aaron Wile, 'Watteau, Reverie, and Selfhood' in The Art Bulletin, College Art Association, 2016