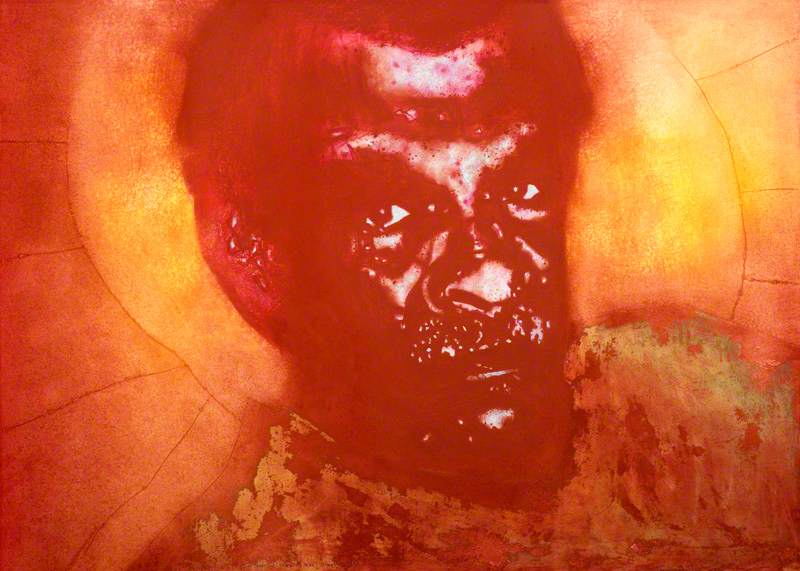

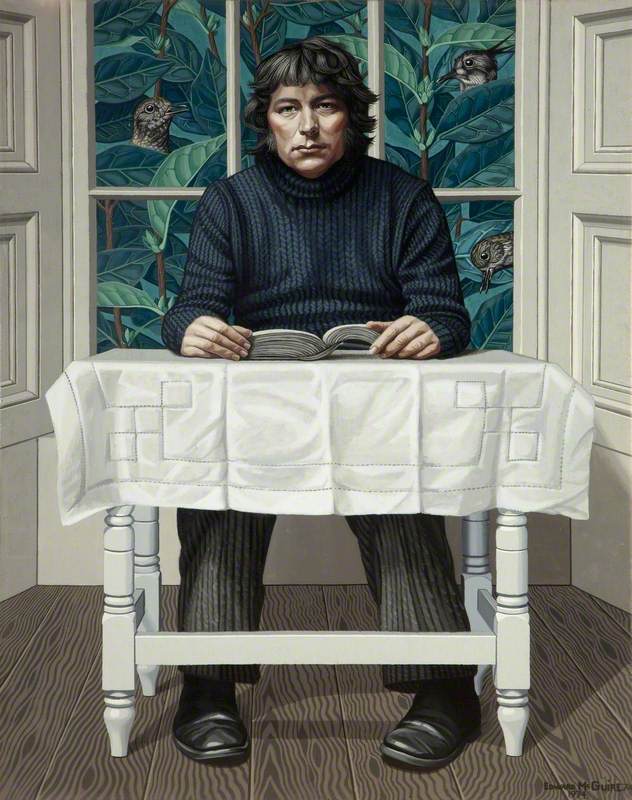

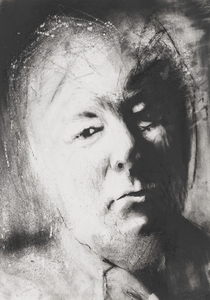

Some of us may be poets at heart, but in the hearts of many poets is a painter: Derek Walcott was one of them. When the National Portrait Gallery asked Ross Wilson to paint a portrait of the esteemed Saint Lucian Nobel Laureate, he thought it was a friend's idea of a prank and didn't call the Gallery back for three months. Eventually, in 1997, Wilson found himself travelling to meet the poet in the Caribbean.

Three years earlier, Wilson had produced a portrait of Walcott's close friend, fellow poet and Nobel Laureate, Seamus Heaney. No doubt this portrait had something to do with the Walcott commission, but Wilson himself had personal reasons to paint Walcott which ran deeper than his recent portfolio.

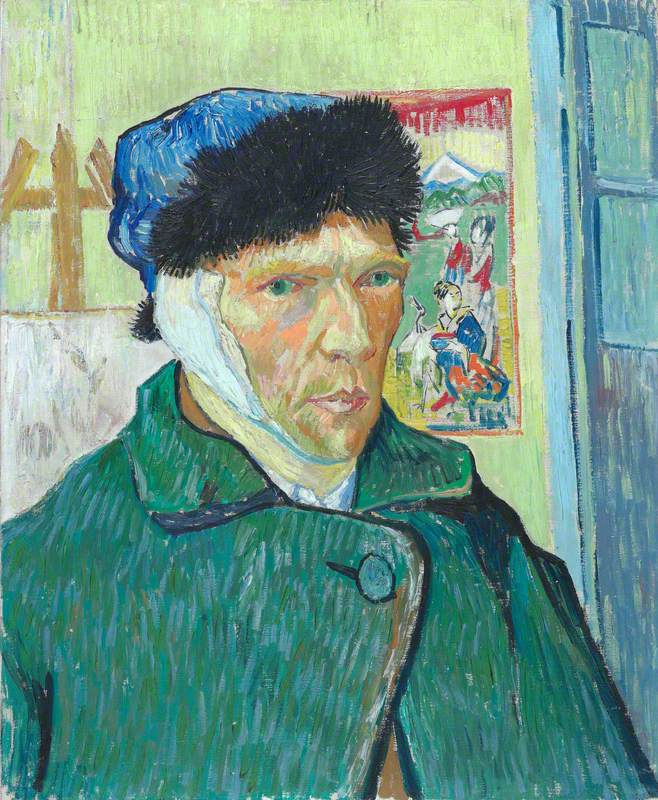

Wilson, who lectures on the life and works of Vincent van Gogh, has always been interested in the fact that the Dutch master and artist-saint of the nineteenth century was born one year to the day after another Vincent van Gogh, an older brother who died shortly after birth. Every morning, in the graveyard of the church his father ministered in, the young painter walked past a headstone bearing his own name. 'I've often wondered,' says Wilson, 'if Vincent was trying to live two lives, if he was trying to live for the first Vincent as well as himself.' Wilson concedes that this is a 'heady concept to consider,' but perhaps it is this chimeric conception of an artist that Wilson also saw in the Saint Lucian poet.

Walcott had already long identified with Van Gogh. In his early autobiography, in the verse 'Another Life', he wrote:

'Remember Vincent, saint

of all sunstroke, remember...

The sun explodes into irises,

the shadows are crossing like crows

they settle, clawing the hair,

yellow is screaming.'

Walcott never tired of this thrill of recognition with the Dutch Post-Impressionist painter. Van Gogh's The Sower (1889) was the basis of Walcott's occasional poem on the election of Barack Obama in 2008, and his last play O Starry Starry Night (2014) was a dramatisation of Paul Gauguin's 1888 visit to Van Gogh in Arles.

Walcott's father, also a poet and painter, died when Walcott and his twin brother Roderick were only a year old. 'My father,' Walcott wrote, whose 'preferred medium' of watercolours, 'made him my precocious fiction.' When asked whether he was living for his father as well, Walcott said 'I think so, at least in terms of my duty' – a duty to a father who was 'torn from developing what he might've done.'

For many artists, it takes a whole lifetime to convey light in the way Van Gogh or Walcott could. Perhaps their work blazes with redoubled intensity because they had two lives to illuminate.

It is now a cliché to say that a light that burns twice as bright burns half as long, but a more 'heady concept to consider', in relation to Wilson's portrait, is whether such a light burns twice as hot. Light, in the end, can only come from heat. Speaking of Van Gogh's changing palette as he moved south, Ross Wilson said: 'All of a sudden his paintings were filled with heat and sun and light and colour that you can almost feel pushing out of the canvas, or pushing from behind the canvas, as if someone has a bright light shining from behind the canvas through the brushstrokes.' In his own way, Wilson was trying to convey something similar in The Sun Poet, as he said himself, 'I wanted it to be really hot, full of heat' (i).

Today’s #portraitoftheday is St. Lucian poet, playwright, theatre director and #NobelPrize winner Derek Walcott.

— Portrait Gallery (@NPGLondon) November 20, 2020

Derek Walcott ('The Sun Poet') by Ross Wilson, 1997 pic.twitter.com/w1nL7IDh9F

In Wilson's portrait, Walcott is the pulsing, magma-coloured afterimage that haunts our vision after looking at the sun. Such intensity of light burns a hole right through us: Wilson's composition is evocative of how Walcott's poetry paints images of such vibrancy that can only be comparable to sunlight in the mind's eye. Philip Larkin once wrote (in 'Water', 1988) that if he were called upon to construct a religion, he would make use of water, 'where any-angled light / would congregate endlessly.' Walcott's oeuvre, 'wet with light', is just such a consecration – the praise and elation of light. Walcott said that he 'never separated the writing of poetry from prayer. I have grown up believing it is a vocation, a religious vocation.'

The portrait feels as if the sun is shining through Walcott, revealing his features the way thermographic cameras reveal heat signatures and long infrared waves paint a red world on our eyelids in the sun. But at the same time, the light can be seen shining directly onto Walcott's face, casting him as a friend or a teacher, its intense heat finding a kind of peace, a tranquillity of focus, mesmerising 'like fire without wind,' in the same way Walcott said that if you 'stand close to a waterfall you will stop hearing its roar.' His expression is both serious and warm, like the sun, but perhaps its defining quality is patience.

The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last berth to be broken up, 1838

1839

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Walcott's shirt of gold, weathered by history, slouches toward the bottom-right corner of the portrait in the same way the light of J. M. W. Turner's sunset falls in The Fighting Temeraire, or as Walcott put it, in 'Another Life', 'a sun, tired of empire, declined' and 'the sky / grew drunk with light.' Around Walcott's head is a line, reminiscent of the 'oblate orange' described in James Joyce's Ulysses, from which more lines stream ever outward like sunbeams or poetry.

Hard to miss is Walcott's right ear, which looks like boiling hot blisters or a slice of pomegranate – or perhaps that is a spot-fire in my retina. I do not know why Wilson painted Walcott's ear this way, but it might have something to do with the fact that staring at the sun burns the eye: a poet's light burns our ears longest. Or perhaps Wilson, like Vincent van Gogh, knew how expressive the listening device of the ear can be. In 1887, Van Gogh painted a concerned-looking self-portrait (now hanging in Kunstmuseum den Haag) in which his ear looks similarly damaged, even vandalised. Only a year later, Van Gogh did mutilate his ear, slicing through the facade between art and life.

For Walcott – and for Van Gogh too, if you read his letters to his brother Theo – the only real difference between visual and literary art is that the former appears in the world before our eyes, and the latter appears in the world behind our eyes. Poetry and painting are like waves reaching the shore, each arriving in its own way but expressive of the same thing. Or, as Walcott put it:

'...in every surface I sought

The paradoxical flash of an instant

In which every facet was caught

In a crystal of ambiguities,

I hoped that both disciplines might

By painful accretion cohere

And finally ignite'

– from Derek Walcott's Another Life (1973)

According to the Oxford Classical Dictionary, ekphrasis refers to 'the literary and rhetorical trope of summoning up – through words – an impression of a visual stimulus, object, or scene.' When it comes to Walcott's 'ekphrasis of relation' (ii), as University of Essex scholar Maria Cristina Fumagalli has called it, his last major work, Morning, Paramin (2016) is probably the most conspicuous. He sought to blur these boundaries further by putting 51 new poems alongside 51 works by contemporary artist Peter Doig in a single volume.

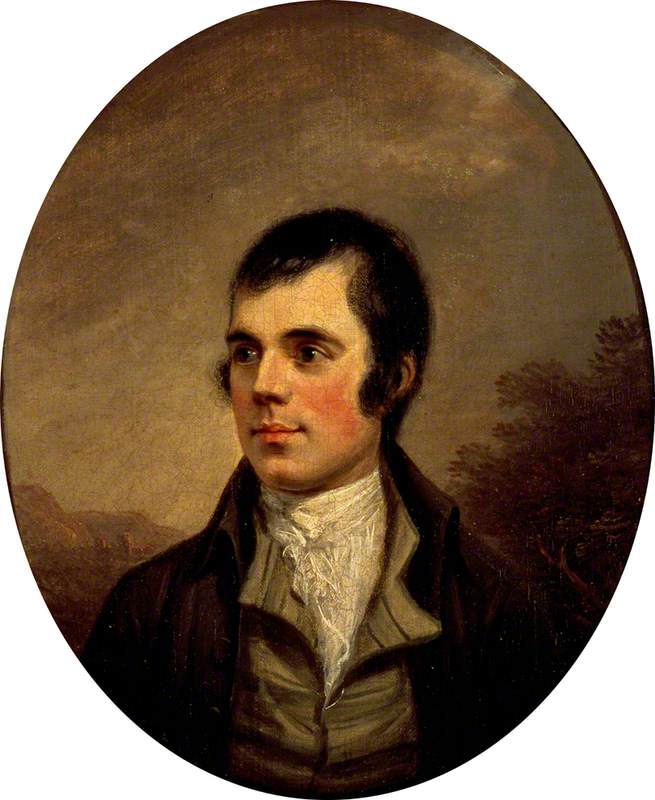

But Walcott's ekphrastic passion was there from the beginning: the opening poetic image in his first published volume, 25 Poems (1949), written at age 18, was of 'fishermen rowing homewards in the dusk', who 'Do not consider the stillness through which they move'. With its dusky twilight and picturesque drama, the poem's imagery resembles the first painting Turner exhibited at the Royal Academy, Fisherman at Sea.

Though Walcott had a particular affinity for 'Van Gogh's shadow rippling on a cornfield' and 'Cézanne's boots grinding the stones of Aix', he understood the debt Impressionism owed to Turner. In 'Another Life', a young Walcott dissolves into a trance upon a hilltop and falls into the orbit of poetic vision, and there 'in drizzling twilights, Turner'.

In his youth, Walcott took on a painting apprenticeship with his friend Dunstan St Omer under the tutelage of St Lucian artist Harold Simmons. St Omer became a distinguished painter and muralist, while Walcott became a poet who wrote with the vividness of paint. In his poetry, he could concentrate entire images into the horizon of a line and entire histories into metaphor.

'The chronology of clouds

contained the curled charts of navigation,

battles with smoke and pennants, shrouds

of settling canvas, as afternoon descended

past the cobalt wall of the sea to a faint

vermilion and orange, and the sky overhead

ripened to a Tiepolo ceiling. All was paint'.

– from Derek Walcott's Tiepolo's Hound (2000)

In addition to portraits of Walcott and Heaney, Wilson also painted the American playwright Arthur Miller. Wilson believes that what these writers have in common is an ability to 'Touch the light... to allow us to see things' (iii). When Wilson asked Miller what it was he was doing when he wrote a play, Miller replied, 'It's about hitting the light. We do it so rarely in life. It's about illumination.' In Wilson's portrait, he hit the light, allowing us to see Walcott in the heat of creation, an image of 'The Sun Poet' from the perspective of the page.

Blake Matich, writer, poet and journalist

(i) Ross Wilson, 'An Evening with Artist Ross Wilson', Wade Center, 2018

(ii) Maria Cristina Fumagalli, 'Morning, Paramin: Derek Walcott, Peter Doig, and an Ekphrasis of Relation', New West Indian Guide, 1–29, 2018, p.1

(iii) Ross Wilson, 'Real Lives Service – Ross Wilson', Emmanuel Baptist Church