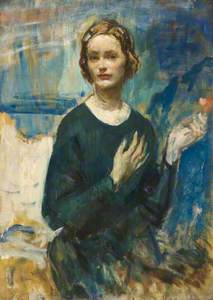

Described as a modern Gainsborough and tenderly

However, within 30 years, his portraits were no longer fashionable, his work was described as exhibiting ‘startling vulgarity’ and his contribution to British art was soon forgotten. New research has recently discovered that even the year of his birth has been incorrectly documented as 1878. He was in fact born the previous year on the 12th August 1877 in Crudwell, Wiltshire.

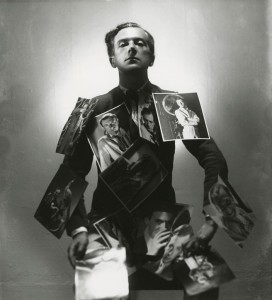

Captain Martin Eric Nasmith, VC, Royal Navy

1918

Ambrose McEvoy (1878–1927)

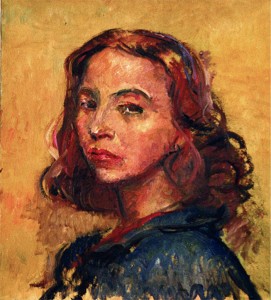

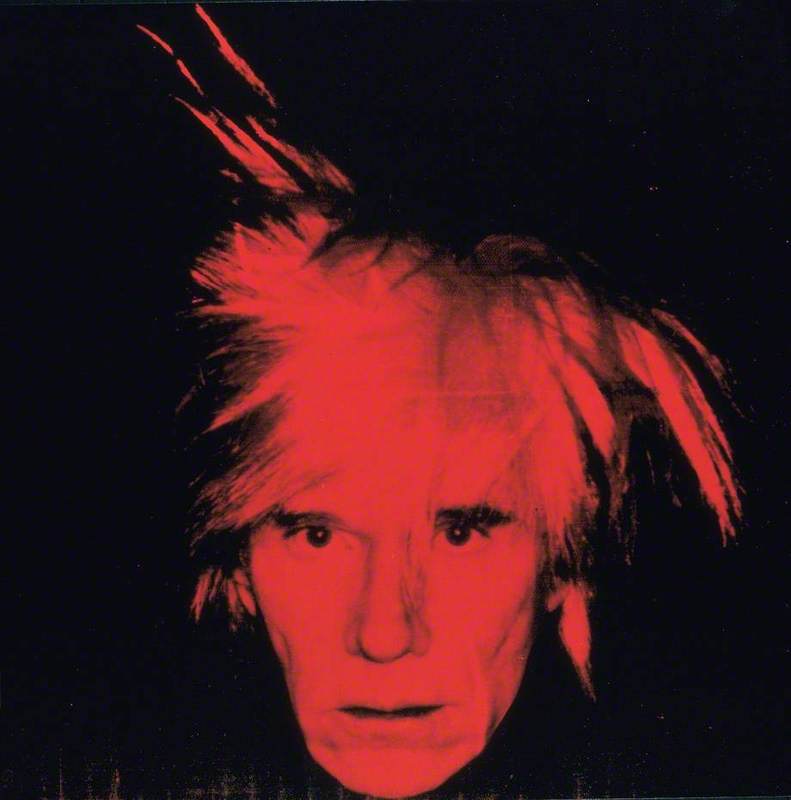

His portraits, defined by broad, impatient brushstrokes, are largely experimental in their impressionistic style and can be described as combining classical painting with modernism. Although his subjects are often sedentary, McEvoy successfully dictates a sense of movement through his furious

Ambrose McEvoy’s artistic talent was

It was at the Slade that McEvoy became friends with the artist Augustus John who described McEvoy, with his monocle, his straight black hair and his black suit, as owing his appearance to Whistler – he was a perfect ‘arrangement in black and white’.

Whereas John was interested in Watteau and Rembrandt, McEvoy was inspired by the early Italians and the English Pre-Raphaelites and spent his time copying works by Titian and Velasquez in The National Gallery. It was almost certainly this meticulous replication of Old Masters that encouraged McEvoy’s interest in figurative painting and developed his unique ability to capture

In 1909 McEvoy visited Dieppe with Walter Sickert, who was well-acquainted with the French Impressionists and established a long-term friendship with Edgar Degas. McEvoy became influenced by Sickert’s looser technique and in the years that followed he embarked on an increasingly impressionistic style. He became a founder member of the National Portrait Society in 1911 and during the First World War spent three months on the front line producing several portraits of naval officers, these are now in the Imperial War Museum in London. Although his war portraits are very accomplished, it was his paintings of female subjects that made him famous. His full-length portrait of Maude Louise Baring (née Lorillard), the daughter of an American tobacco magnate, defined McEvoy as a fashionable portrait painter amongst the London elite.

Throughout the first half of the 1920s, whilst Cecil Beaton was photographing the Bright Young Things (the famous group of salacious and bohemian young socialites), McEvoy was painting them. Amongst his sitters were the Jungman sisters, Teresa and Zita, Lady Diana Cooper, Diana Manners and the famous Lois Sturt, wild child and the Brightest of the Bright Young Things. It was these portraits that not only made McEvoy increasingly sought-after in the 1920s but eventually led to his posthumous downfall, in an exhausted post-war Britain which had outgrown its interest in risqué young aristocrats.

In 1924 at the peak of his career, McEvoy was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy and a member of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters. However, overwork took its toll and he died only three years later on 4th January 1927, a week after contracting pneumonia. His wife Mary and two children, Michael and Anna, survived him. Although the work of Ambrose McEvoy has been overlooked since his premature death, he contributed hugely to early modern British portraiture with transitioning styles and constant experimentation in technique. His portraits, although working from weeks and months of sittings with an individual, appeared effortless to his contemporaries and his close friend Augustus John wrote, after McEvoy’s death, that he ‘never seemed to work hard but had

Lydia Miller, Former Researcher at Philip Mould & Company and Current

Further reading

‘Obituary. Mr. Ambrose McEvoy’, The Times, 1927

‘Ambrose McEvoy: A Cautionary Tale Re-Told’, The Times, 1953

D. Pollen, I Remember I Remember, privately published, 2008, p.158

Augustus John, Autobiography, 1975, p.52

W. Rothenstein, Men