William Wilson OBE RSA, known as 'Willie' to his friends, was a twentieth-century maestro in printmaking, watercolour and stained-glass design. To mark 50 years since his death in 1972, an exhibition at the Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture is the first to survey Wilson's diverse practice in nearly 30 years.

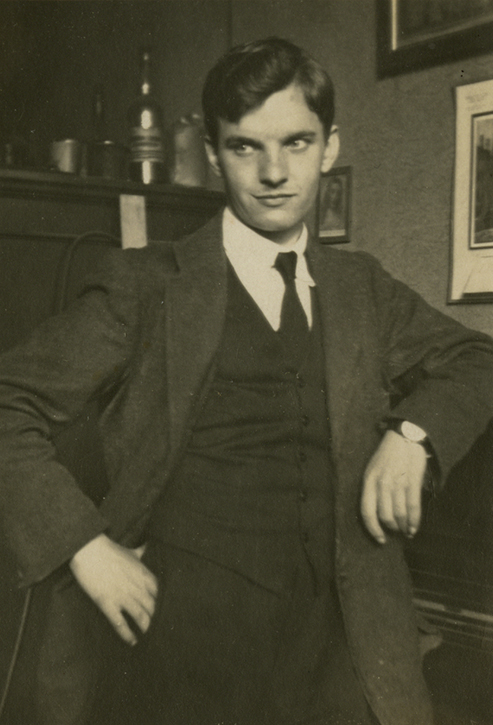

Image credit: courtesy of the artist's estate

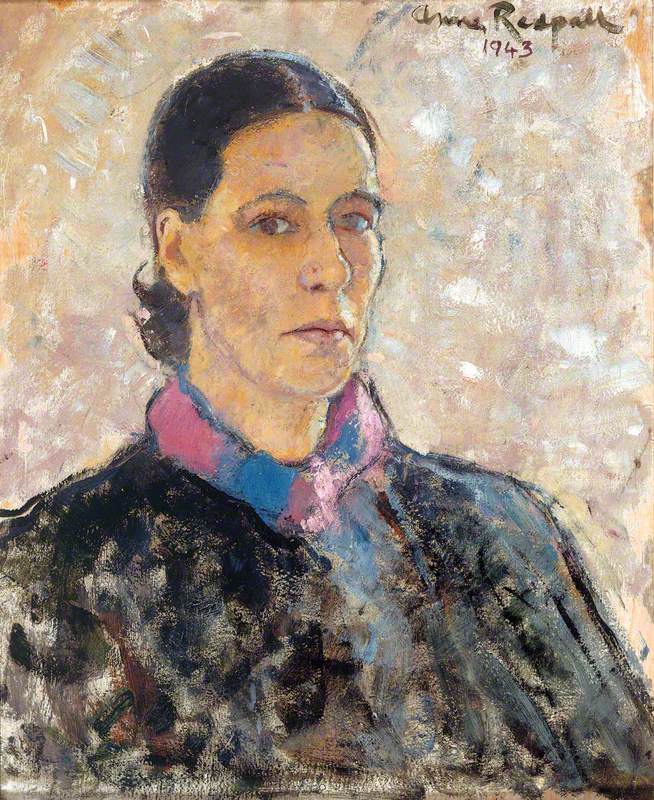

Portrait of William Wilson as a young man

The eldest child of a watchmaker and jeweller, and nephew to the painter, printmaker and stained-glass artist Thomas Wilson, William Wilson was born in Edinburgh in 1905.

From an early age, his compelling interest and passion was drawing, a love that would grow into the skilled draughtsmanship evident in his diverse career as an artist. He was educated at Sciennes School and took an early job at Bartholomew's, an Edinburgh map maker, before beginning as an apprentice at the stained-glass studio of James Ballantine in 1920.

Around the same time, Wilson began to attend evening classes at Edinburgh College of Art. Here he attracted the attention of Adam Bruce Thomson, who persuaded him to enrol as a full-time student in 1932. A sign of Wilson's talent, in this year he would win the Royal Scottish Academy Carnegie Travel Scholarship, which took him to France, Italy, Spain and Germany.

Bridge of the Scaligers, Verona c.1932

William Wilson

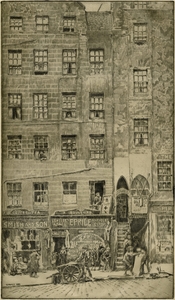

On his travels he studied stained glass, visited museums and galleries, and sketched widely in preparation for making prints upon his return to Scotland. Travel was a major source of inspiration to Wilson's early prints, which show an acute awareness of Western art and a precocious technical mastery in the difficult technique of engraving, in which the artist creates an image by scraping a needle into a soft metal plate. Early examples, such as A Tuscan Hill Town, show an amazing mastery of the needle.

A Tuscan Hill Town c.1929–1932

William Wilson

A Tuscan Hill Town (original print dated 1930) 2019

William Wilson, Leena Nammari

From engraving, Wilson's printmaking focus would move into etching. This allows a freer and more expressive approach due to the technique of drawing the image into a wax ground, which is then exposed to acid to 'etch' the image onto the copper plate beneath.

One print in particular, St Martin's Bridge, Toledo, 1933, shows the early signs of Wilson's mature style and his visionary interpretation of landscape. At a large scale for prints of the time, it was a precursor to the group of powerful Scottish prints Wilson created from 1934 to 1937.

St Martin's Bridge, Toledo 1933

William Wilson

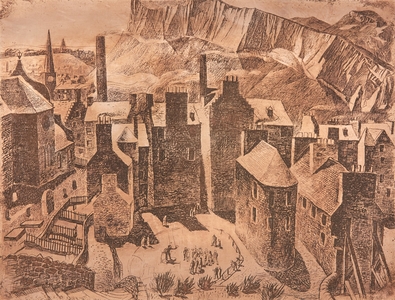

Including North Highland Landscape, Sutherland and Loch Scavaig, these sizeable prints take your breath away in their dramatic and exaggerated depiction of rocky Highland landscapes, usually highlighted with vignettes of human structures and figures going about their daily lives.

The figure groups in his prints show the influence of Pieter Bruegel the elder and Lucas Cranach the elder, and German art had a lasting impression on Wilson and his art.

North Highland Landscape (original print dated 1934) 2019

William Wilson, Leena Nammari

Following the likes of D. Y. Cameron, Muirhead Bone and James McBey, Wilson and compatriots such as Ian Fleming and James McIntosh Patrick can be credited with sustaining and evolving the Etching Revival of the late nineteenth century well into the twentieth century in Scotland. E. S. Lumsden had been instrumental to this, and Wilson followed him into the Society of Artist Printmakers, becoming its Honorary Secretary in 1933, a post he would hold until 1947.

Although many of the great prints of the early twentieth century survive, this does not apply to the plates that were used to create them. As an expensive commodity, copper was often repurposed, and so the gift to the RSA in 2017 of 18 copper plates (a few double sided) for some of Wilson's most noteworthy prints, was significant.

To celebrate the gift, the RSA commissioned Academicians Stuart Duffin and Leena Nammari to create contemporary prints from the plates. These prints are labelled as proofs 'after Wilson', as the original artist was not around to give them his seal of approval, but they nonetheless stand as a valuable and striking record of the irreplaceable plates in the RSA collections.

Sutherland Landscape (original print dated 1934) 2017

William Wilson, Stuart Duffin

The relationships and dialogues between artists embody the RSA over its near 200-year history. Each new Academician is elected by those already elected – it was Adam Bruce Thomson who nominated Wilson for election in 1938. On his nomination form, Thomson wrote 'Painter and Etcher and worker in Stained Glass'. At the time, the RSA was an Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, and Wilson was elected as a painter at first nomination, becoming an Associate in 1939, before being promoted to full Academician rank in 1949.

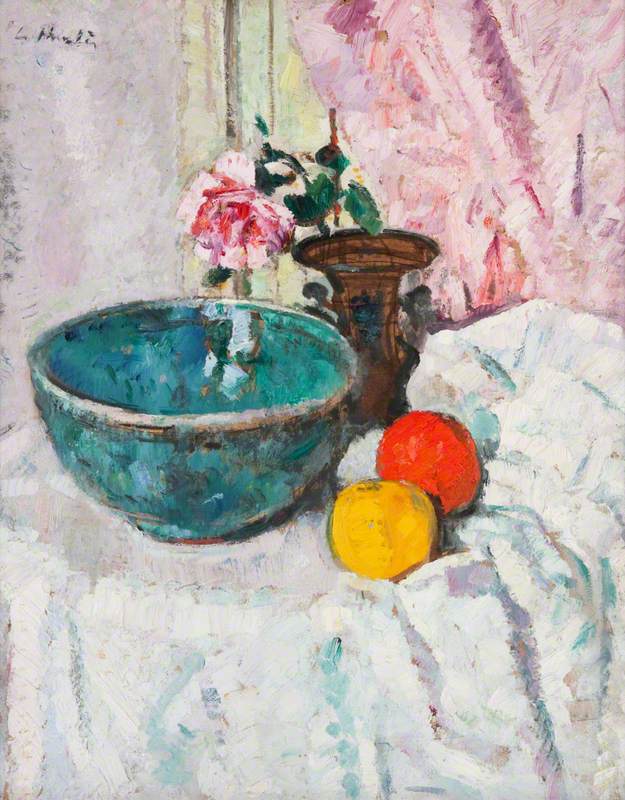

In the mid-1930s, Wilson began to focus on watercolour painting. This was perhaps influenced by the restriction of disciplines at the RSA, and encouragement from his Edinburgh School peers, such as his close friend Anne Redpath.

He exhibited his first watercolours at the RSA in 1936, including Salisbury Square, London, which retains a close feel to the drawings made for his etchings. However, his watercolour style would soon harness the fluid properties of the medium and a free and loose approach to colour would, with the likes of William Gillies and John Maxwell, transform the watercolour scene in mid-twentieth-century Scotland. Paintings such as Tréboul show this deft handling, set off with quick, bold and dark lines in ink, which emphasise structure and create form.

Progressing from his printmaking, Wilson's watercolours retain an interest in human concerns, but the built environment and harbour scenes take over from the grand landscapes of his late Highland prints. Soul, character and drama are never far away, however, and Wilson infused his buildings with a personality that transcends his paintings from mere architectural representation.

Connections abound within Wilson's art, and they often trace back to and through his stained-glass practice, whether it be the sublime and divine in his printmaking, or the perfectly judged placement of sections of colour in his watercolours.

Stained glass was where it all began for Wilson, and it was where it would all end. Tragically, in the late 1950s he began to lose his sight as a result of diabetes, and the condition would render him entirely blind by around 1962. Wilson exhibited his last watercolour at the RSA in 1960, but would continue his stained-glass studio until 1970, instructing his assistants Jock Blyth and Carrick Whalen to create designs in the inimitable style he had developed over the past 40 years.

Wilson's apprenticeship at Ballantines provided him with the tools and training to master stained glass, but it was an encounter with Douglas Strachan's windows in Robert S. Lorimer RSA's National War Memorial that inspired him as to its potential as a contemporary art form. Following Strachan, Wilson can be credited as one of the stars, if not the star, of the twentieth-century stained-glass revival in Scotland.

Wilson had opened his own stained-glass studio in 1937, but the war soon interrupted his business. Not one to rest on his laurels, he created and exhibited a group of secular panels on themes of his own choosing. These included Wartime Figure Group, which, even in its modest form, shows the multitude of different influences and styles Wilson would command in much grander settings in his window commissions.

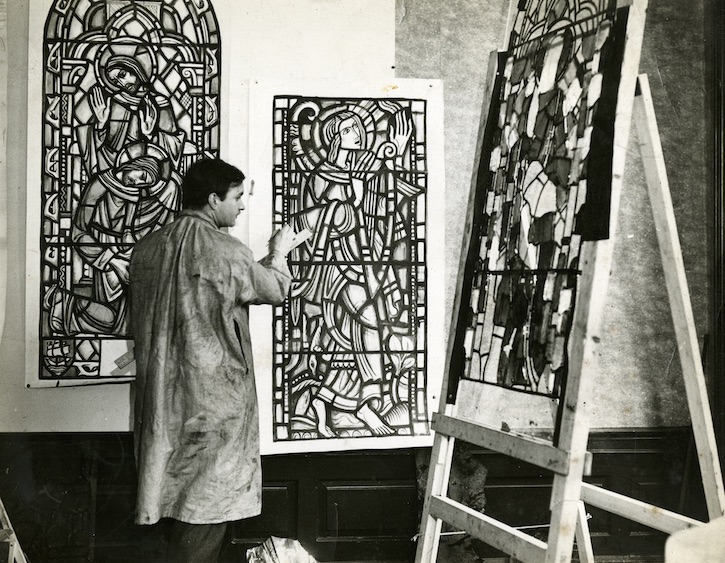

Image credit: courtesy of the artist's estate

William Wilson in his studio with the cartoon and glass pieces for the British Empire Exhibition

After the war, Wilson's stained-glass business began to take off. He moved into a new studio at 11a Belford Mews, which had previously belonged to Phyllis Bone. The sculptor Hew Lorimer had been its first artist inhabitant and it would later belong to the painter Alberto Morrocco.

He promptly hired a group of assistants to help with the many commissions he was receiving, and the studio became a hive of activity; outstandingly, Wilson created over 400 windows worldwide in around 30 years.

Image credit: courtesy of the artist's estate

William Wilson and his assistants with a section of a stained-glass cartoons

Wilson's painterly training brought a fluid, balanced design and brilliance of colour to his windows, while his skill as a draughtsman delivered a unique linear strength through the window's lead lines, or calms. His original stylistic approach to drawing was inspired by German Expressionism, and is most apparent in the heads, hands and feet of his figures.

There is a nod to the colourful luminosity and simplicity of medieval stained glass, but a special fluency of movement and a humanity gives Wilson's windows an expression all their own. Icons, symbols, figures, and often glimpses of buildings and landscapes, as found in his etchings and watercolours, would be composed into dancing patterns of colour and light. A lover of music, Wilson once described them to Sir Harry Jefferson Barnes very simply as 'playing tune, in line and glass'.

Image credit: courtesy of the artist's estate

William Wilson with John Piper at an exhibition event

Willie Wilson was a most popular and gregarious character, who, in addition to his own practice, threw himself into the activities of the RSA and the other arts institutions he was part of.

Returning to his studio from late-night dinner parties after his days of exertion, he would often excuse himself to rescue a stained glass from the kiln with 'I've got an Angel in the oven, he should be about ready by now'.

In 1972, Wilson passed away in Bury after moving south to live with his sister as his health failed. With his passing, Scottish art was robbed of a true genius, who shaped the history of not one, but three distinct art forms.

Fortunately, in collections and in public buildings and churches across the UK and beyond, his marvels in print, paint and glass can be discovered and enjoyed for years to come.

Sandy Wood, Collections Curator at the RSA

'William Wilson: Print | Paint | Glass' is at the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture until 13th November 2022. It can be viewed online