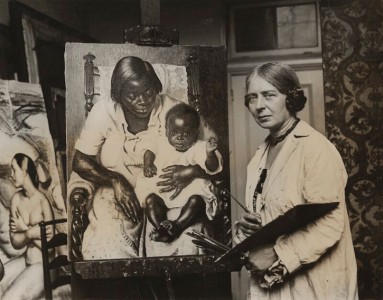

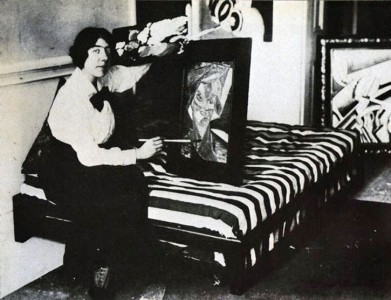

Anna Airy (1882–1964) was greatly appreciated in her lifetime. Her work evidences the continuing realist tradition in British art of the early decades of the twentieth century, displaying an astonishing degree of technical accomplishment. But as modernism became dominant after the Second World War, Airy and many of her realist contemporaries were sidelined and, for the most part, forgotten. A re-evaluation of their work is long overdue.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council CollectionAnna Airy was of English and German descent: born on 6th June 1882, in Greenwich, to an engineer father, Wilfrid Airy, and a German mother who died two weeks after her birth. An only child, Airy was raised by two unmarried aunts, both competent artists, who undoubtedly encouraged the gifted young Airy in her painting, as did her father.

Airy recalled her father saying that 'if I persisted in going in for art when I left school that he would give me the finest art education either in this country or on the Continent that could be had at that time, after which I must stand on my own two feet'.

Airy trained at the Slade School of Art, London (from 1899 to 1903) where she won all the top prizes and scholarships. Just two years after leaving the Slade she had established herself in a studio in West Hampstead and had a first painting accepted for the Royal Academy Summer exhibition. This was a sensitive portrait of a veteran of the Indian Army, Michael Lee, Esq, described by the art critic of The Hampstead and Highgate Express as 'one of the best pieces of actual painting' in the 1905 exhibition.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

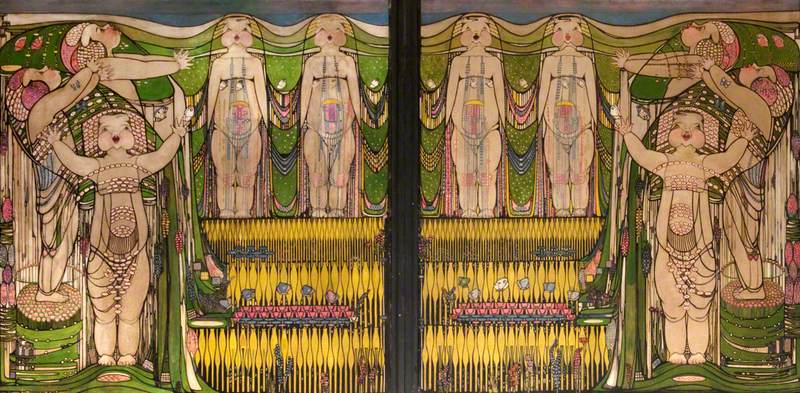

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council CollectionEach succeeding year Airy contributed a major composition to the Academy's Summer show. Initially her exhibits portrayed single figures, but by the 1910s she was producing more complex compositions on varied themes. Some, such as Autumn Treads where Summer Ran, displayed considerable charm or were sumptuously decorative as in The Flower Shop.

View this post on Instagram

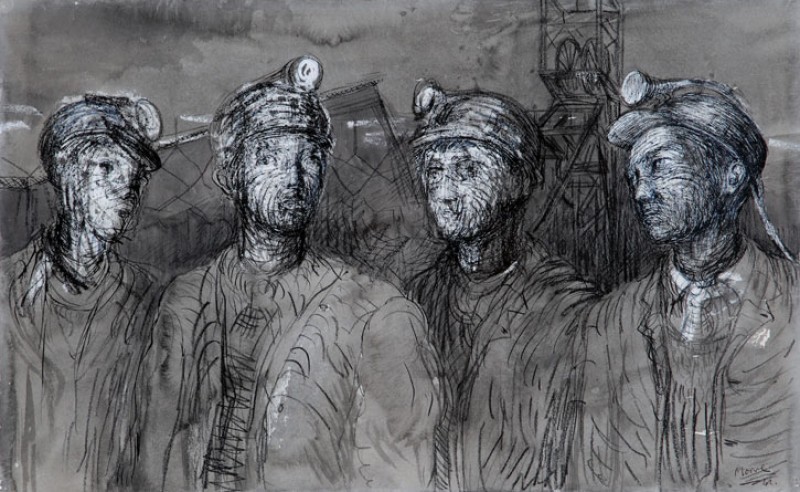

As a student, keen to know something of 'life in the raw', something very different to her comfortable, middle-class existence, Airy had sought out the Thames-side underworld of bare-knuckle boxing and illicit gambling dens. These night-time explorations inspired such works as The Gambling Club, Error in Pay, and A Cast of Dice. Airy would produce these works in her studio which she shared with fellow artist Geoffrey Pocock whom she married in 1916.

Airy carefully managed her professional career realising the importance of putting her work before the public as consistently and widely as possible to establish and maintain a reputation. In addition to the Royal Academy, she submitted work to the annual exhibitions at the Institutes of Fine Arts in Liverpool and Glasgow, as well as contributing to various exhibiting societies that all elected her to membership.

By the time of her 30th birthday in 1912, these included the Pastel Society, an Associate of the Royal Society of Etcher-Painters and of the Royal Society of Oil Painters. Full membership of these latter two societies soon followed, as well as of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters and the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolour.

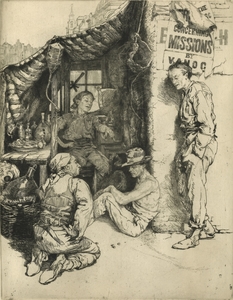

Airy also had her work selected for inclusion in both national and international group exhibitions. For example, her etching Greengages was included in the Whitechapel Gallery's landmark 1910 exhibition 'Twenty Years of British Art' and her watercolour Willow Pattern had place-of-honour at the 1912 International Exhibition of Fine Art in Rome.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: courtesy of Ipswich Art Society

Willow Pattern

1906, watercolour and pen by Anna Airy (1882–1964)

A contemporary article in The Studio identified her as 'an artist of exceptional interest'. Airy also mounted two solo London shows – the first at the Carfax Gallery (1907) and the second at Paterson's Galleries (1911).

These solo London exhibitions showcased Airy's versatility in terms of media. Works were shown in oils, pastel, watercolour and etching. Their wide-ranging subject matter included portraiture, still life and studies of the natural world. Childhood summers passed in the Suffolk countryside had nurtured in Airy a passion for nature which found expression in meticulously detailed botanical studies such as Willow Pattern, a tour-de-force of Dürer-like observation.

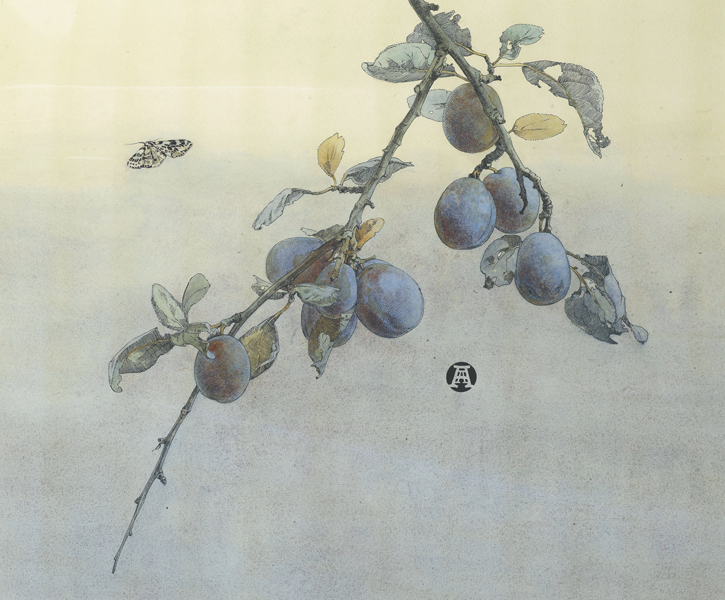

In many of these watercolours and etchings, a Japanese influence is evident in her depiction of sprays of blossom, pendant fruit or insect-ravaged leaves. The exquisite quality of these studies brought Airy much critical appreciation and they were frequently reproduced in publications such as Colour and The Studio. The latter, in June 1915, devoted a five-page illustrated article to them.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: Sarah Colegrave Fine Art

Leopard Moth and Plums

Watercolour by Anna Airy (1882–1964)

Airy's high public profile by the outbreak of the First World War led to her being one of the few women chosen to be a war artist. Her first commission was from the Canadian War Memorials Fund Committee. Cook-house, Witley Camp (now in the Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, Canadian War Museum) was the result.

More important, was the subsequent commission Airy received from the Munitions Committee of the Imperial War Museums. This was to produce four large-scale paintings depicting munitions workers involved in various aspects of heavy industry pivotal to the war effort.

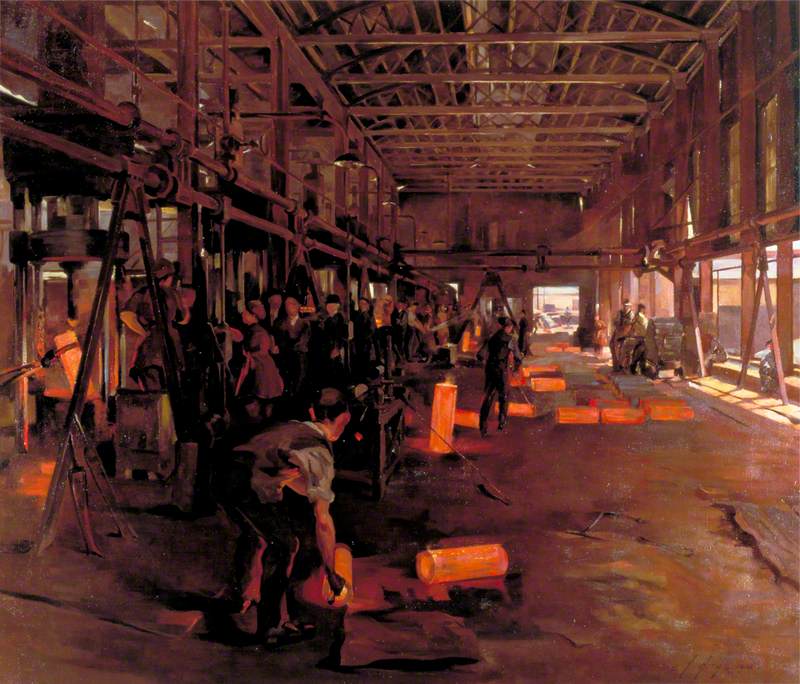

Image credit: IWM (Imperial War Museums)

Shop for Machining 15-Inch Shells: Singer Manufacturing Company, Clydebank, Glasgow 1918

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

IWM (Imperial War Museums)Particularly striking is Airy's painting of the vast interior of the Singer Manufacturing Company in Glasgow which had changed from producing sewing machines to manufacturing the high-calibre artillery shells employed on the Western Front. The accuracy with which Airy depicts the complicated factory infrastructure well displays her understanding of the shell manufacturing process. The muted colours and subdued light filtering through the factory roof emphasise the grim nature of the work undertaken by the mostly female employees.

Image credit: IWM (Imperial War Museums)

Women Working in a Gas Retort House: South Metropolitan Gas Company, London 1918

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

IWM (Imperial War Museums)Women Working in a Gas Retort House was Airy's final war commission from the Women's Work Sub-Committee. The clouds of white smoke and orange and yellow flames leaping out from the furnace on the left of the painting dramatically portray the harsh conditions under which these workers laboured to produce gas from heated coal.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: The Collection: Art & Archaeology in Lincolnshire (Usher Gallery)

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

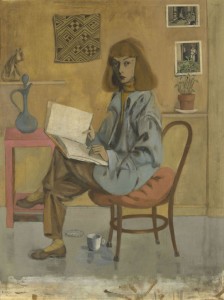

The Collection: Art & Archaeology in Lincolnshire (Usher Gallery)Following the war, during the 1920s and 1930s, Airy's complex figure compositions assumed a more playful air, many with a rural theme. Children Blackberrying is a typical example. Airy also continued to paint portraits, some commissioned and others for personal interest as is the case with the pensive portrait of Greta – a young woman on the verge of adult life.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council CollectionIn Interior with Mrs Charles Burnard Airy's interest has shifted from sitter to the light and reflections handled in this composition.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

Interior with Mrs Charles Burnand 1919

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council CollectionAiry's enjoyment in the sheer technicality of representing such reflections led during the 1930s to atmospheric virtuoso paintings such as July Piece.

In 1933 Airy and her husband left London to live permanently in the Suffolk village of Playford near Ipswich. Despite comparative isolation, Airy continued to exhibit both nationally and internationally with continuing commercial success. For example, Message of May sold for the highest price at the 1938 RA Summer Exhibition (800 guineas) – a considerable sum at the time.

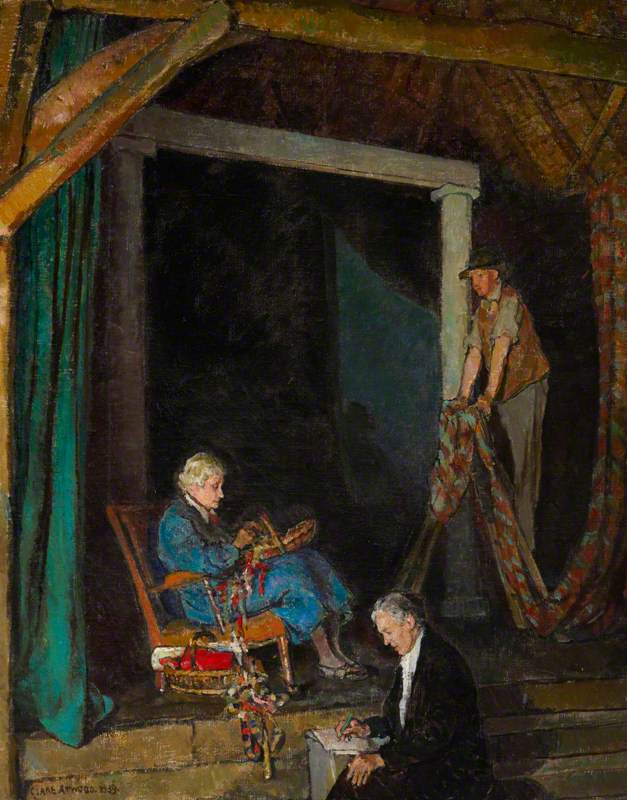

In 1943 Airy held a highly successful solo exhibition in Ipswich (her thirteenth). Two years later she was elected as the first female President of the Ipswich Art Society and became highly influential in that role. Local residents recall her 'brilliant and inspirational' teaching, an activity that she had always enjoyed and which led to her writing two practical guides – The Art of Pastel (1930) and Making a Start in Art (1951). In these, she defined the creative process as 'a subtle and sensitive feeling... primarily and irrevocably based on Nature and Truth.'

It seems unjust that the work of Anna Airy – who assiduously and successfully devoted her career to the painting of such 'Nature and Truth', and at a time when there were few celebrated women artists – is so little known and appreciated. As the mainstream story of twentieth-century British art grows broader, and with a growing appreciation of traditionalist approaches, it might be hoped that the time has now come for a major retrospective of Airy's work.

Alison Thomas, freelance writer and curator

.jpg)