The German painter Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) once said that an image 'is no more responsible for superstitious abuse than a weapon is responsible for a murder.' And yet, the history of destroyed and damaged art is paradoxically a testament to the power of images. Bliss, awe, melancholy, resentment, irritation, even boredom: stand before a work of art and you're sure to feel something. The recent toppling of monuments associated with slavery and colonialism across Europe and the US is the latest in a long line of more radical reactions.

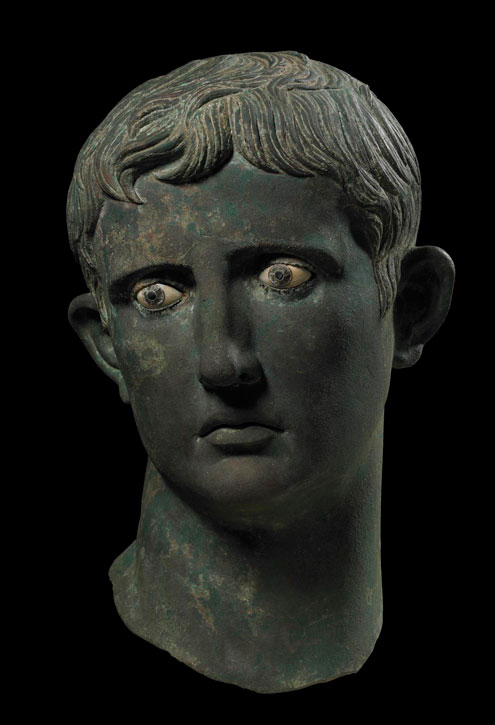

That line stretches back to ancient times. Take the bronze portrait head that once capped a statue of the Roman emperor Augustus (r.27 BC–AD 14).

Official portraits of the emperor were erected across Egypt after it became a Roman province in 31 BC, and a few years later some were captured by an invading Kushite army. This larger than life-size head – decapitated but otherwise in good condition, with sticking-out ears and glaring eyes of coloured glass and white stone – was buried beneath the steps of a temple at the Kushite capital, Meroë. Trampled by his captors, the emperor's head wasn't seen again until the site was excavated in 1910. Rediscovered, he retained his commanding stare.

The @britishmuseum has a wonderful short guide to the bronze head of Augustus. Includes these amazing images of the excavations in Meroe, Sudan, that led to the discovery of the head by archaeologist, John Garstang. https://t.co/zVG6kGgEk9

— Dr Sophie Hay (@pompei79) August 24, 2018

Photos originally from @GarstangMuseum pic.twitter.com/oZCdm8SHMC

In images of holy people and biblical scenes it was often the eyes that sparked the destruction of icons. In some cases, they were gouged out to prevent eye contact with impressionable viewers. In a more recent incident in 1905, a visitor to the Alte Pinakothek in Munich took a hatpin to the searing pupils of Dürer's self portrait of 1500.

Self Portrait

1500, oil on lime wood by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

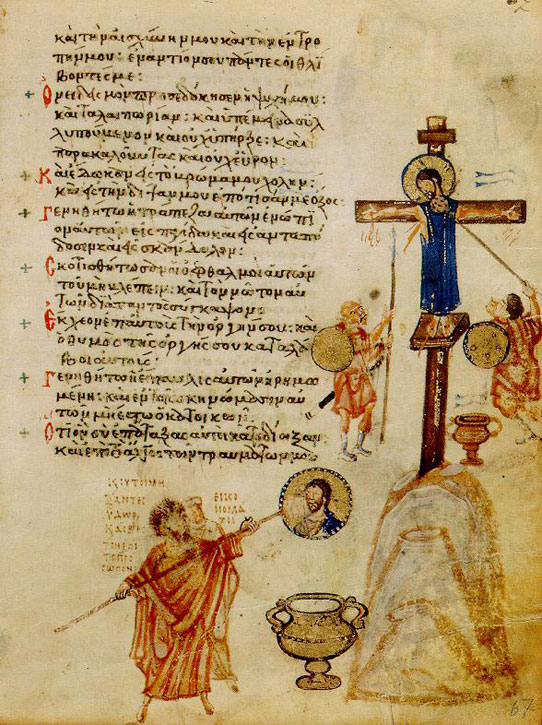

Among the earliest iconoclasts were eighth-century Christians in the eastern half of the Roman empire. In 730, Byzantine emperor Leo III banned the production and veneration of religious images and set out to demolish or cover up existing examples. A lengthy conflict ensued: while the upper class generally adhered to the ban, the disadvantaged fought to retain their beloved icons, which they believed were vital to social cohesion. The ninth-century Chludov Psalter shows an iconoclast whitewashing a portrait of Christ.

The manuscript's creator made his views clear in his rendering both of the iconoclast and the pair of Roman soldiers torturing Christ – all wear fiery red robes and wield similar-looking instruments (though the iconoclast's pole is attached to a sponge rather than a spearhead).

The first English iconoclasts made their mark, so to speak, in the sixteenth century. Religious reformers, rallied by the dissolution of monasteries engineered by Henry VIII's minister Thomas Cromwell, stripped Roman Catholic churches and monasteries bare.

Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex

(copy after an original of 1533–1534) late 16th C

Hans Holbein the younger (c.1497–1543) (copy after)

A statue of the dead Christ (c.1500–1520) is a rare survivor of the destruction wreaked on holy images and objects first during the Protestant Reformation and later during the English Civil War.

Is this the finest piece of pre-Reformation sculpture in the UK? Recumbent dead Christ. Mercers Hall. London. pic.twitter.com/QQdvzNBE5H

— Geoffrey Munn (@GeoffreyMunn1) August 29, 2015

The mutilated sculpture was buried beneath a chapel in the Mercers' Hall in London – most likely to prevent further damage – and rediscovered in 1954. Christ is missing his arms and lower legs, as well as his crown of thorns.

Reformers feared the blurred line between real and represented – the sinful worship of a sculpture of Christ instead of Christ himself – and that line is just as hazy when we leave the religious realm. Damage is often done to art because art is regarded as a proxy for the person or ideologies it represents.

After the outbreak of the English Civil War, parliamentarians stormed Winchester Cathedral and fired shots at a gilded-bronze statue of Charles I by the French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur (c.1580–1658) – a royalist allegedly bought it later in the seventeenth century and buried it for safekeeping. Likewise, the bronze statue of Charles I in Trafalgar Square was hidden and only reappeared once the monarchy was restored.

Meanwhile, Robert Walker's portrait of a young Oliver Cromwell – who had Charles I executed in 1649 – was reportedly hung upside down by the steadfast monarchist Frederick Duleep Singh.

Now it hangs (the right way up) in the Inverness Museum and Art Gallery, the Lord Protector's armour gleaming against a muted backdrop.

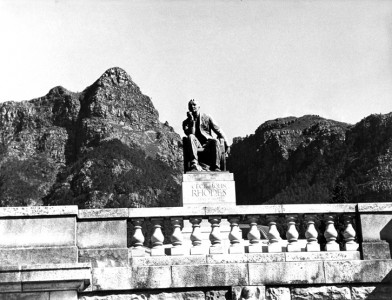

When heads of state are overthrown, felling monuments to them reenacts their fall from power. Roused by the public reading of the Declaration of Independence on 9th July 1776 in New York City, American soldiers and sailors dismantled Joseph Wilton's gilded equestrian statue of the British monarch George III in Lower Manhattan – it was melted down to make more than 42,000 musket balls. The horse's tail is on display at the New York Historical Society. This 1850s painting by Johannes Adam Simon Oertel imagines the scene of it being toppled.

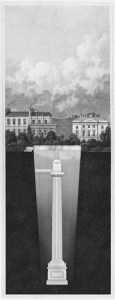

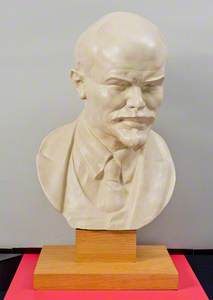

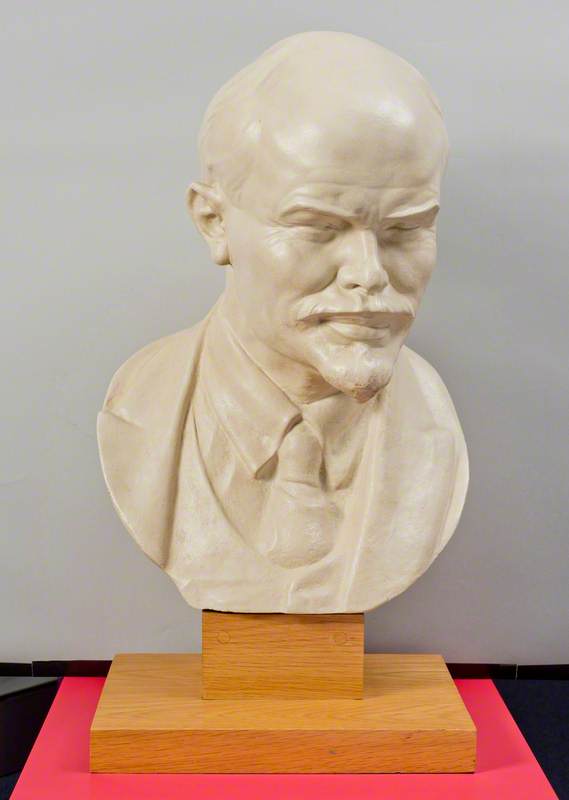

In 1942, after Russia became Britain's ally in the Second World War, Berthold Lubetkin's monument to Vladimir Lenin was erected in Holford Square in the north-London neighbourhood of Islington as a symbol of camaraderie. Some Londoners bucked against the celebration of Communism and vandalised the bust, which was moved into storage before being displayed at Islington Town Hall, where it was vandalised again – this time with blood-red paint.

Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), Leader of the 1917 Russian Communist Revolution

1942

Berthold Lubetkin (1901–1990)

In 1956, during Hungary's October Revolution, anti-Soviet crowds tore down the Stalin Monument, a bronze statue erected in Budapest as a gift to the 'Man of Steel' on his 70th birthday. All that remained were his boots.

Fast-forward to 2003 and American troops in Baghdad toppled a statue of Saddam Hussein, cheered on by locals. Captured on film, the event became powerful propaganda.

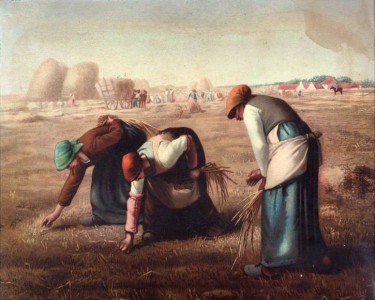

Not all attacks on art celebrate change – some seek to bring it about. The suffragettes famously slashed works in their fight for equality and the release from prison of Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the Women's Social and Political Union. Among the works targeted were paintings of female flesh laid out for the pleasure of male viewers. At London's National Gallery, Mary Richardson hacked at Diego Velázquez's great The Toilet of Venus ('The Rokeby Venus').

Vandalised 'Rokeby Venus', 1914

(cuts made by Mary Richardson in 1914 using the meat cleaver shown in the top-right corner) .jpg)

In a statement, Richardson said, 'I have tried to destroy the most beautiful woman in mythological history.'

The Toilet of Venus ('The Rokeby Venus')

1647-51

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

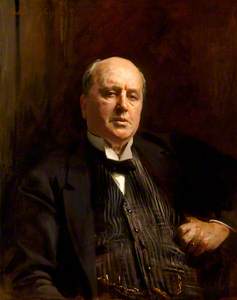

That same year fellow suffragette Mary Wood took a meat cleaver to John Singer Sargent's portrait of Henry James in the Royal Academy – a painting of an eminent male novelist by an eminent male artist. At that time, there had been zero female Royal Academicians since Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807) and Mary Moser (1744–1819), who were founder members in 1768.

For the suffragettes, destruction was a creative force – and they were not alone. Artists themselves have been known to bin their work or, as with Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) by Willem de Kooning's friend Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), mutilate it as part of the creative process.

In 2018, Banksy stunned onlookers when he shredded his Girl with Balloon (2006) after it was purchased at Sotheby's New York.

Whether or not he knew how high the value of the work would subsequently climb is open to debate, as is his motivation. Was he wagging a finger at art-world wealth? Nodding to the vandalisation of graffiti out on the streets? He later claimed that the shredder malfunctioned: the work should have self-destructed entirely.

To destroy a work of art is to make a statement, whether religious, political, social, aesthetic – or all of the above. Let's not forget, too, that some artworks fall victim to natural disaster and others – like us – were never meant to live forever.

Today the toppling of historical figures is dividing opinion: some are cheering their belated removal, while others are up in arms about what they regard as historical revisionism. If this long line of destroyed and damaged art can teach us anything though, it's that knocking down a sculpture doesn't mean erasing history. Rather, it means reconsidering the values we want to promote in the present.

Chloë Ashby, freelance writer and editor

.jpg)