What is the first thing that comes to mind when you read the phrase 'History of Science'? Some might imagine spaceships, or Einstein's unruly hair. If so, then the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, in Cambridge, perhaps presents a quite unexpected imagining of the subject.

The Museum displays historical objects that narrate many different aspects of what we now call science. Although the word itself has been used since the fourteenth century, 'science' didn't become the term for a particular approach to the pursuit of knowledge until the nineteenth century. Throughout history, humans have tried to understand the world we live in – the species that we encounter; the character of substances dug from the ground; how our bodies work – and the Museum collects instruments and models that reflect this pursuit of natural knowledge. With a particular focus on objects used between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, the collection illustrates how people made sense of the world through the design and use of diverse instruments, models, apparatus and related materials.

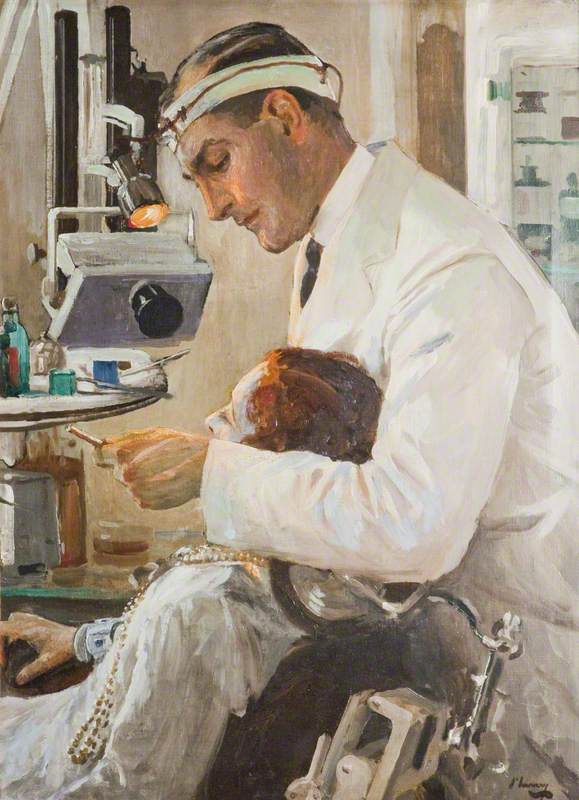

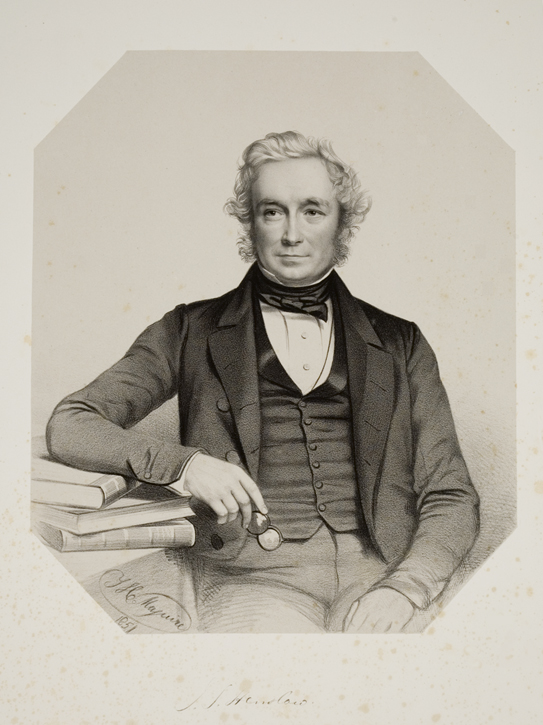

Robert Whipple (1871–1953)

1950

Mary Marriot

The Museum was founded with the donation of the private collection of Robert Stewart Whipple (1871–1953), a local industrialist who worked at the Cambridge Instrument Company, eventually rising to become its Managing Director and Chairman. His path onto the 'slippery slope of collecting', as he described it, began in 1913 with the purchase of an old telescope in the town of Tours in France.

Refracting telescope

1700–1750, vellum, paper, wood, horn by Leonardo Semitecolo

The Museum currently holds about 8,000 objects and the associated Whipple Library holds a large number of rare books. Besides tools of science such as telescopes, microscopes and sundials, the collection also includes many other objects that have helped us understand the world such as models, wall charts, machines, diagrams and toys. The objects highlighted in this article show us the different ways in which science has been studied, but also showcase the ingenuity in their design and manufacture, which is both scientific and artistic. Though the term 'beautiful' is less commonly associated with great achievement in science, we would like to highlight some of the beautiful works held within the Whipple Museum's diverse collections.

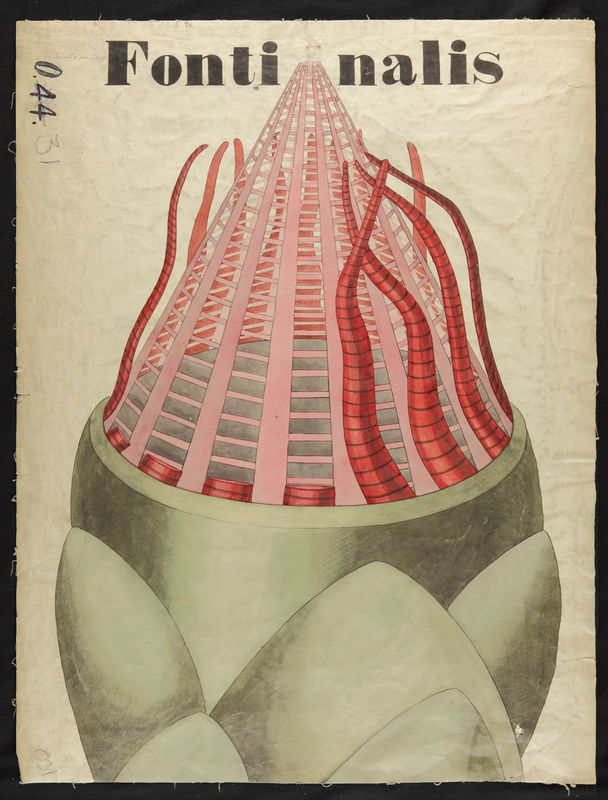

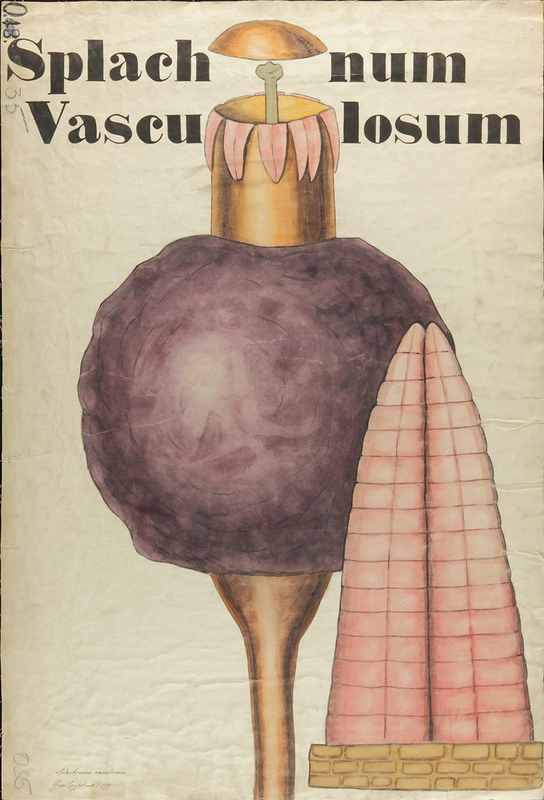

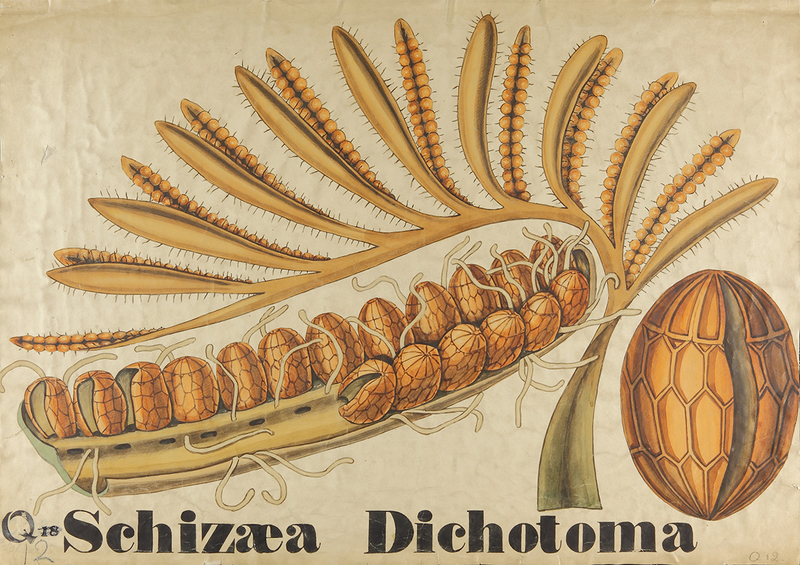

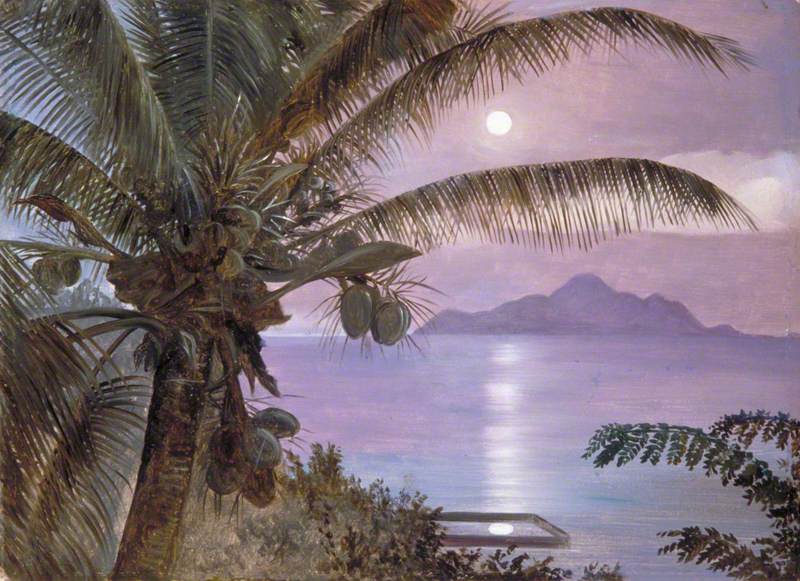

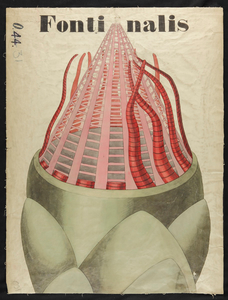

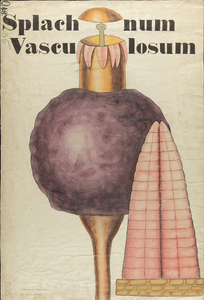

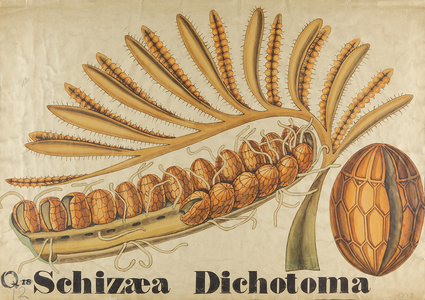

Plant illustrations

For much of the history of botany, it has been common for botanists to hold the paintbrush and secateurs at the same time. The Whipple Museum has a large collection of botanical teaching diagrams, both printed and hand-painted. These include important works by, for example, John Stevens Henslow and Arnold and Carolina Dodel-Port. A small number of these amazing wall charts are now highlighted on Art UK.

John Stevens Henslow

1851, print by Thomas Herbert Maguire (1821–1895)

John Stevens Henslow (1796–1861) and his son George (1835–1925) were both influential British botanists that were educated at the University of Cambridge. Though he modestly claimed to know 'very little' about botany, John Stevens Henslow transformed the subject at Cambridge, including moving and redesigning its botanical garden, which opened to the public in 1846.

Botanical Teaching Diagram of Root Vegetables

1827–1861

John Stevens Henslow

The father and son duo created over 100 colourful diagrams for use in teaching, including the example above, illustrating different forms of taproots. Hand-painted on a large scale, the diagrams were designed to be used in a lecture theatre and were still in use in the 1960s.

Botanical Teaching Diagram of Pinus Laricio

1878

Arnold Dodel-Port, Carolina Dodel-Port

Swiss husband-and-wife team Arnold (1843–1908) and Carolina (b.1856) Dodel-Port collaborated for their publication Atlas der Botanik. The wives of botanists often illustrated their husbands' books, but this atlas is unusual in crediting both authors equally. The two works above are signed with Arnold's and Caroline's names separately.

Botanical Teaching Diagram of Cydonia Vulgaris

1860–1890

Arnold Dodel-Port, Carolina Dodel-Port

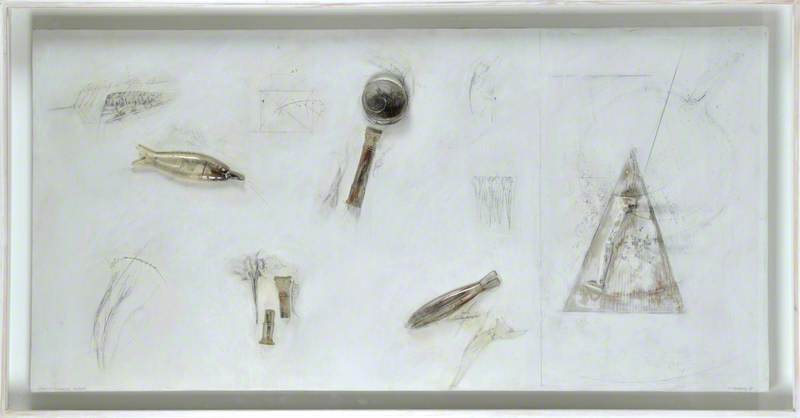

Models

Three-dimensional objects can help words come to life, especially if the pieces are designed to be handled. Models are not only convenient for enabling students to look at complex and minute details: in the examples shown here, they're also works of incredible artistry.

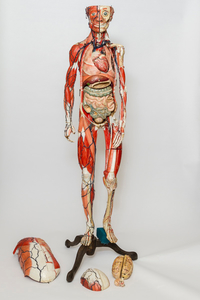

Anatomical Model of a Human

1837–1920

Louis Thomas Jérôme Auzoux

Dr Louis Thomas Jérôme Auzoux (1797–1880) was a medical student when he first noticed the scarcity of human bodies for dissection in medical schools. After much endeavour and trial and error, he finally found the perfect formula for a special kind of papier-mâché for making human anatomical models. His models were much cheaper than wax equivalents, easier to acquire than cadavers from morgues, and durable enough to be handled multiple times.

The model in the picture above is a classic example of Auzoux's work. The body parts are removable, with labels indicating the names of hundreds of anatomical features. The Whipple's staff call him Marcel, and he always greets people with a big smile!

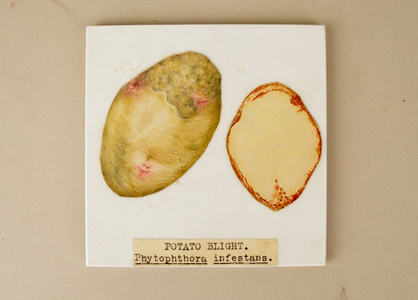

Ceramic Tiles with a Drawing of Infected Potatoes

1930–1953

William Dillon Weston

Another alumni of the University of Cambridge, W. A. R. Dillon Weston (1899–1953) was a mycologist (someone who studies fungi) that worked for the Ministry of Fisheries and taught mycology at the University. During the 1930s, he created more than 1,000 watercolours that depicted diseases on plants, especially fungal infections. These works allow us to see a meticulous mind that worked between science teaching and art making.

The work shown above depicts a potato disease, phytophthora infestans – more commonly known as the potato blight – that is notorious for its role in the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s. Dillon Weston has stuck his watercolour onto a ceramic tile, for reasons that are still unknown.

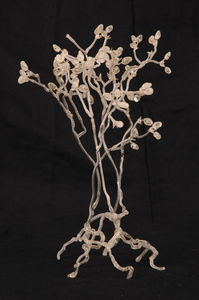

Glass Model of Fungi

1930–1953

William Dillon Weston

Another amazing legacy of W. A. R. Dillon Weston, these glass fungi models show us what tiny fungi look like without the need for a microscope. As a getaway from his insomnia, Weston hand-crafted almost 100 glass fungi models for teaching and researching. The shimmering material and its fragility certainly is a spectacle as well as an example of the power and influence of mycology.

Glass slides

The Museum also has a great number of glass slides used for magic lantern projection and stereoscopic viewing. These slides not only show us the history of science presentation but also record the authors' methods for making and disseminating new knowledge. These kinds of slides appeared before photography, and the illustrations reflect common subjects and artistic choices chosen for wider demonstration.

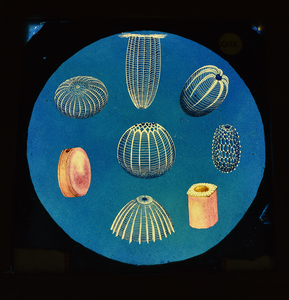

Magic Lantern Slide of Sea Urchins

1880

William Henry Dallinger

Reverend William Henry Dallinger (1839–1909) was, as his title suggests, a religious person, but he was also passionate about science teaching and learning. He was an avid supporter of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection and conducted experiments on single-celled organisms. He argued that creationism (the religious belief that lifeforms were created by God) was 'untenable'. Science and Christianity, from his perspective, do not clash.

Magic Lantern Slide of Pink Coral

1880

William Henry Dallinger

These beautiful glass slides, along with another 100 that are housed in the Museum, were used by Reverend Dallinger in 1884 for a lecture in Montreal. In the lecture, he talked about the emergence of forms of life, such as micro-organisms, that refuted the idea of life coming from non-living materials (abiogenesis).

The Whipple Museum has made its whole collections database publicly available online. As a subject that is often seen as complicated and logical, science and its history are too rarely associated with art. Yet, besides busts and portraits of great scientists, there is a great deal more that we can appreciate while we learn about scientific achievements through these collections. We hope that our collections on Art UK will interest those who seek both art within science and science within art.

Guey-Mei Hsu, Collections Assistant, Whipple Museum of the History of Science