We previously wrote about some of the big-name films that have starring roles for works of art, including Skyfall, Ferris Bueller's Day Off and The Thomas Crown Affair.

We've once again delved into the crossover worlds of oil paintings and cinema: and once again, the films that feature famous artworks have turned out to be from remarkably different genres.

It's time for art in the movies: the sequel.

Titanic: a drowning Degas

Yes, Titanic has the famous scene where Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio, playing an artist) sketches his lover Rose (Kate Winslet), sans clothes.

But other art, by real artists, also gets a look-in in Titanic. Just after Rose has boarded the ship, her belongings are being unpacked in her sumptuous quarters. Alongside the clothes and other home comforts comes her collection of art, including some now-famous artworks: Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and Degas' L'Etoile. Neither of these paintings live in the UK, but Degas' Dancer on a Stage features a similar composition to L'Etoile ('the star').

The scene is clearly designed to show off Rose's taste and empathy, as she declares the paintings by then-unknown artists as 'fascinating... like being inside a dream or something'. It's also a quick and easy way to show that her fiance, Cal, has no taste, as he is dismissive of '...something Picasso'. We feel no sympathy when Rose jilts him for Jack, who shows off his own artistic tastes when he spots a Monet, exclaiming: 'Look at his use of colour here, isn't it great?'

These paintings were not on board the real Titanic. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon remained with Picasso until 1924, and is now safely in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and L'Etoile lives in the Musee D'Orsay in Paris. Monet painted many versions of Waterlilies, but there are few records of any high-profile artworks on board the ship, so it's unlikely that any of Rose's collection was historically accurate.

James Cameron did not actually obtain permission from Picasso's estate to use Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, and replaced it in the 3D re-release of the film with a shot of the Degas painting – which was out of copyright – submerged in the water.

V for Vendetta: anarchists and Arnolfini

In this film – an adaptation of Alan Moore's original graphic novel – Hugo Weaving plays the eponymous V, a vigilante who teams up with Natalie Portman's Evey to fight Britain's newly Fascist government.

It's not the sort of plot synopsis that makes you immediately think the film will be full of art.

But when Evey wakes up in V's hideout for the first time, she's surrounded by objects he has stolen from the government's Ministry of Objectionable Materials: banned music, film, sculpture and paintings.

Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife

1434

Jan van Eyck (c.1380/1390–1441)

V is the new owner of The National Gallery's Arnolfini portrait and Bacchus and Ariadne, Tate's The Lady of Shalott, Puberty by Edvard Munch, and Elohim Creating Adam by William Blake.

V's impressive collection isn't discussed by the characters, but it implies that he thinks this art and culture worth saving from the clutches of a government that no longer values it – or finds it dangerous and subversive.

Ex Machina: can artificial intelligence make art?

Ex Machina is a film exploring the limits of technology, in which CEO and computer genius Nathan Bateman (played by Oscar Isaac) invites his employee Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) to live and work with him on his latest project: a humanoid robot (Alicia Vikander), who just might be the first ever artificial intelligence.

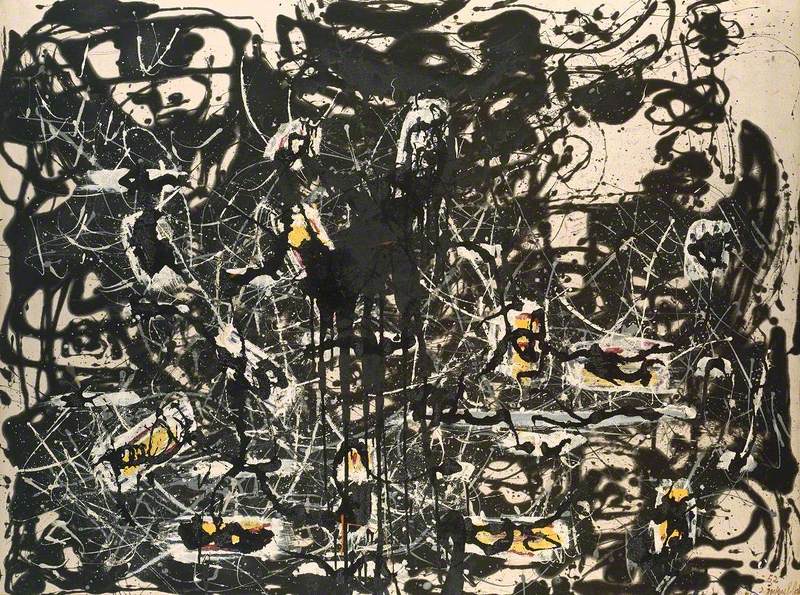

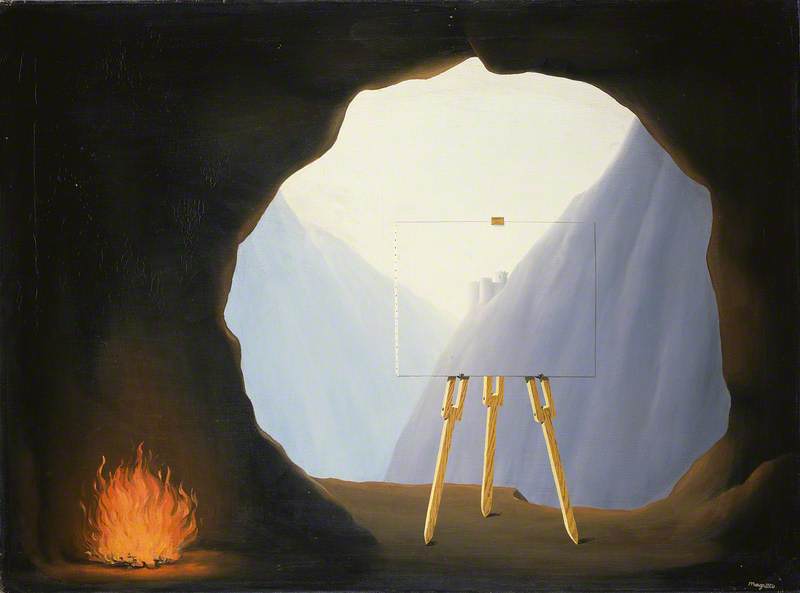

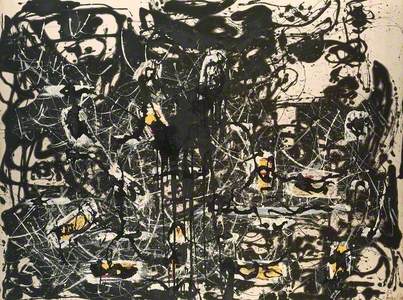

Bateman delivers a mini-lecture to Caleb about the Jackson Pollock painting that takes up a wall of his strange, slightly subterranean house:

'He [Pollock] let his mind go blank and his hand go where it wanted. Not deliberate, not random, someplace in between. They called it automatic art... what if Pollock had reversed the challenge? What if making art without thinking he said, "you know what? I can't paint anything unless I know exactly why I'm doing it." What would have happened?'

What Bateman means by this speech is up for debate. Is he comparing the process of automatic art to his own attempts to create true artificial intelligence? Is he saying that the impulsive, creative spark of an artist is part of what differentiates human from machine? Is this painting the dividing line between us and AI? Or could a robot create a Jackson Pollock that has as much meaning as one created by the man himself?

An Education: an education in the Pre-Raphaelites

Moving from silicon valley to suburbia: this is a coming-of-age drama based on the real-life memoirs of the journalist Lynn Barber. In the film, Carey Mulligan plays Jenny, a 16-year-old who falls for an older man and all of the worldly excitement he brings: jazz bars, cigarettes, trips to Paris, and access to art. In a conversation about buying art at auction, Jenny exclaims: 'I love the Pre-Raphaelites; Rossetti and Burne-Jones anyway, not Holman Hunt so much, he's so garish'.

Later on, Jenny is taken to the auction at Christie's and is prompted to bid on a Burne-Jones: The Tree of Forgiveness. She buys it for 200 guineas, and as they drive away from the auction, Dominic Cooper's character Danny laments that 'just a couple of years ago, you could pick one up for fifty quid'.

A notable point is that the price at auction is given in guineas, a currency that was ended in the Great Recoinage of 1816. But after the introduction of the pound, the guinea continued to be used for 'professional fees and payment for land, horses, art, bespoke tailoring, furniture and other luxury items' – this practice finally ending a couple of years after decimalisation in 1971.

Towards the end of the film, Jenny visits her old teacher and notices that she, too, has a Burne-Jones print in her house, showing them to be kindred spirits.

As an end note, an interesting theme running through these four disparate films is the use of art as a shorthand to indicate sophistication and taste. In Titanic it's used to tell us that Rose isn't just a stuck-up rich girl; in V for Vendetta it represents some of the best assets of society, to be saved from a government determined to stamp out individuality and creativity; in Ex Machina it is the thing that makes us uniquely human; and in An Education it is a key part of a world of taste and sophistication.

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer