Art Matters is the podcast that brings together pop culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

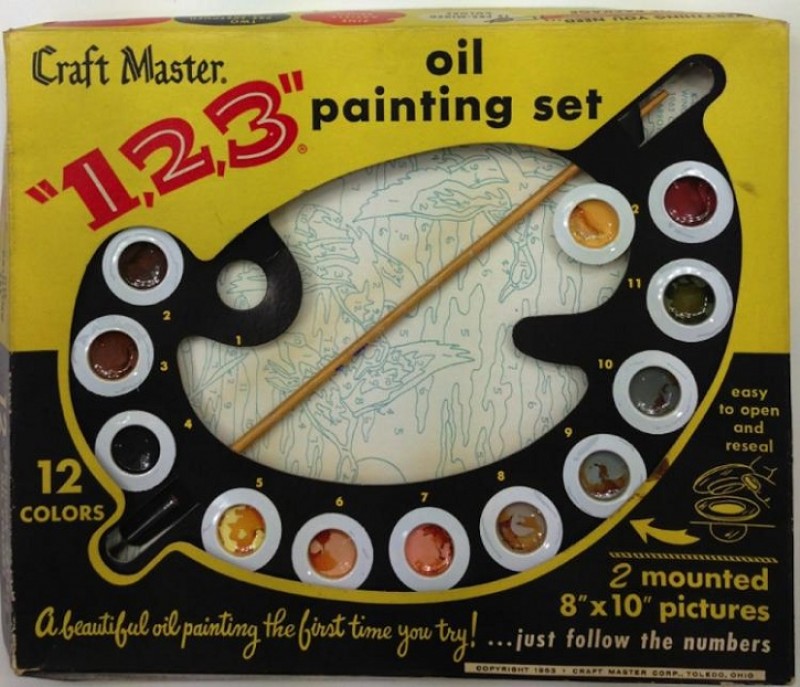

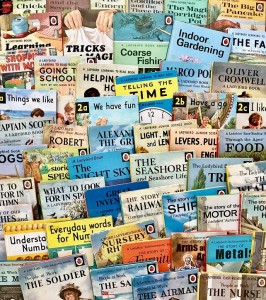

I'm willing to bet that you've probably had a moment where you were standing in a gallery and someone walked up to a painting and proclaimed 'I could do that' before walking off unimpressed – maybe you've even said this yourself. In 1950, Dan Robbins had an idea that would make that statement a reality for millions of hobbyists: paint by number kits. The kits quickly became a popular hobby for amateur artists across the United States, eventually also gaining international success. By proxy, Dan Robbins' paintings made their way into houses all over the world, vicariously making him a highly prolific artist during the 1950s. But how did this start? How did this idea turn into an industry that would generate $80 million in annual revenue at its peak?

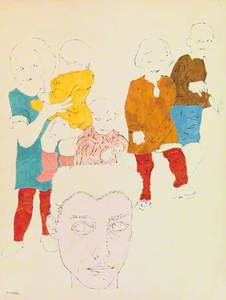

Abstract No. 1: paint by number design by Dan Robbins

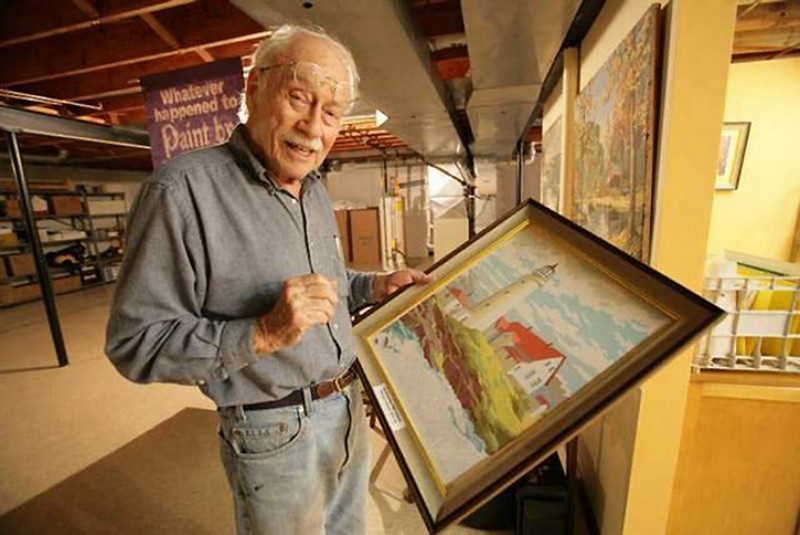

Max Klein was the owner of the Palmer Paint Company, which was originally founded in 1932 to sell paints for commercial signs. When Klein purchased the company in 1945, he wanted to find a way to broaden the business' revenue potential. Enter Dan Robbins. Robbins was an artist who'd begun working with Palmer Paint Co in 1949. '[Robbins] came from a vocational art background, and he remembered a story that he had heard that Leonardo [da Vinci] had farmed out portions of frescos to his students', says William L. Bird, Jr, author of Paint by Number and curator of the 2001 exhibition, 'Paint by Number: Accounting for Taste in the 1950s' at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Remembering Leonardo's number method, Robbins approached Klein with the idea for the kits and eventually his first design, Abstract No. 1.

M-312 Kit: Leonardo da Vinci's 'Last Supper'

'Robbins prepared [Abstract No. 1] and showed it to Klein, and Klein said 'I hate it'', says William. Klein didn't care for the abstract design, but he liked the concept, so Robbins went back to the drawing board coming up with the narrative painting designs the kits are known for today. Designs ranged from simplified reproductions of famous artworks like The Last Supper to still lifes, landscapes and portraits. The limited colour count included with the kits created a degree of

Launching the kits was the first challenge for Klein and Robbins, so they took the kits to the 1951 New York Toy Fair. During the trip, Klein used his contacts to set up a demonstration of the kits at Macy's. 'They flew out of the store', says William. 'Robbins, who witnessed this, was never quite sure if they had left the shelves by themselves or if Klein had gone in with a little walking-around money and paid his friends to take them away to impress Macy's.' However they left the shelves, the demonstration was a success, and five and dime stores, Woolworths, and big department stores across the US began to carry the kits.

during their heyday, the kits were far-reaching – one could find them on the walls across the houses of suburban California to the West Wing in Eisenhower's White House

Eventually, demand for new designs was so high that Robbins' original Abstract No. 1 design was introduced to the collection. A completed version of this kit was entered into an amateur art contest in 1952, winning third prize. As the business grew, the Palmer Paint Company developed levels to the kits, with varying colour counts and themes. They developed a tailored, systematic approach that may have been inspired by some of their

For as many people that loved the pastime, there was some that found it silly and criticised the idea of there being more paint by number paintings than original artworks in homes. There was a perception that maybe it was bored housewives that completed the kits, which possibly contributed to some of the

'The Art Director of Esquire magazine . . . commissioned contemporary artists and illustrators to paint a portrait of President Johnson, who was having trouble finding someone to paint his official presidential portrait', says William. 'He commissioned [Richard Hess], who used to work at Palmer Paint Company for Dan Robbins.' Hess designed a partially completed paint by number portrait of the president, but his cover was bumped for a story by a writer who had an agreement with the magazine. Nevertheless, the Hess cover design went on to win several design

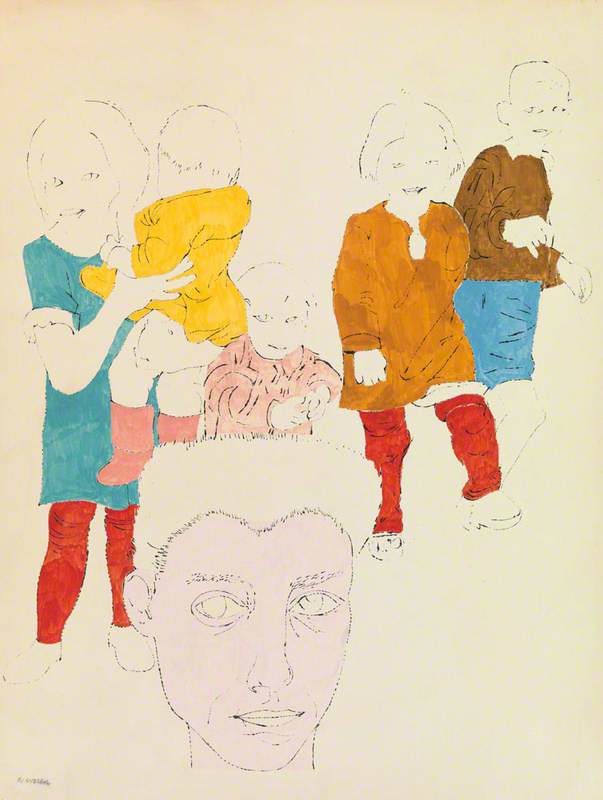

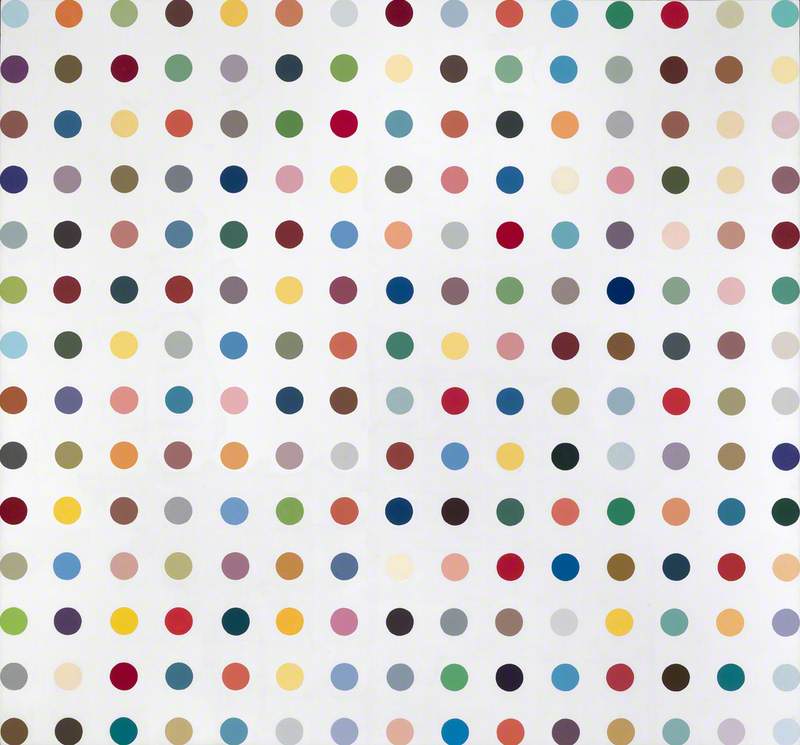

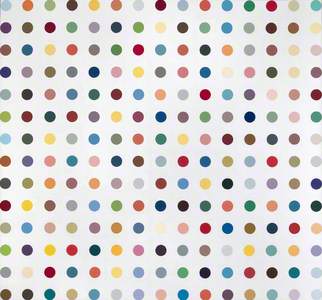

Andy Warhol dabbled in the paint by number technique in his 'Do It Yourself' series. He'd already been experimenting with the idea of partially filled-in illustrations in some of his early work, and the paint by number method married that idea with his desire to find ways of mechanising his process. Fast-forwarding to the early 2000s, Damien Hirst even created his own Painting-by-Numbers kits, where purchasers could create their own version of one of his spot paintings.

Perhaps the growing popularity of television had something to do with its decline of the pastime in the 1960s, or maybe it was the inevitable backlash many pop culture movements face once they become 'too' popular. Still, during their heyday, the kits were far-reaching – one could find them on the walls across the houses of suburban California to the West Wing in Eisenhower's White House. Now, I happily have one hanging in my home.

Out of curiosity, I asked if William enjoyed doing a kit from time to time. 'I did do one', William told me. 'My publisher put out a couple of reproduction prints and I painted one just to see if I could do it. The lines were pretty small – I think I could have done it with a pencil.'

Be sure to listen to the full story of the kits and the 2001 Smithsonian exhibition in the podcast episode above. You can also read more in William L. Bird Jr's book, Paint by Number, and Dan Robbins' book, Whatever Happened to Paint-by-Numbers.

Explore more

Art Matters podcast: artists' love for the

Curating the White House: five things you need to know about art and the presidency

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes