Download and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or TuneIn

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together popular culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

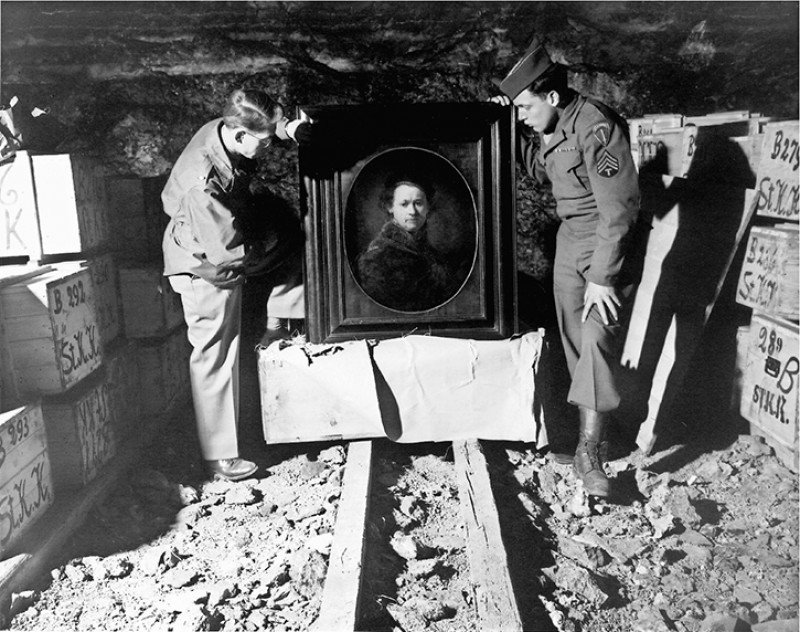

The setting was Europe in the 1940s. The world was at war and communities across the continent were facing destruction. In the course of these events, cultural objects were at risk of theft and historic buildings were being levelled. Amongst these many objects were paintings by Sandro Botticelli, Rembrandt, Jan van Eyck's Ghent Altarpiece, a sculpture by Michelangelo, and more. As a response, the Allied forces assembled a crack team of museum and cultural professionals for the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program – you may have heard them referred to as the Monuments Men. Over the course of its duration, the programme encompassed a group of 400 women and men, initially with specialists from the US and UK and later including participants from liberated countries across Europe.

Bernterode, Germany – May 1945

Monuments Men George Stout (left), Walker Hancock (centre-right), and Steven Kovalyak (right) during the excavation of Bernterode. The soldier standing between Stout and Hancock is a Sergent Travese.

'They were museum directors and curators, artists, architects, librarians, many were archivists,' says Robert Edsel, author and founder of the Monuments Men Foundation for the Preservation of Art. 'They needed all of these different skills in the tasks that they faced.'

The Monuments officers did not directly participate in combat, but some did carry weapons, in part, because their proximity to the front lines put them at risk. Two officers, Captain Walter Huchthausen (American) and Major Ronald Edmond Balfour (British) were killed in combat in April and March of 1945, respectively. It was originally the intent that the officers would follow the front lines, but it became clear that they were needed alongside the troops to prevent theft.

Monte Cassino, Italy – 27th May 1994

Monuments Man Lieutenant Colonel Ernest T. Dewald (centre) makes his way up to the ruins of Monte Cassino, the Benedictine Abbey destroyed by controversial allied bombing in February 1944.

The loss of heritage sites and cultural objects is one of the many atrocities of war. In recent years in Syria, for example, we've seen the tragic destruction of six Unesco World Heritage Sites. There are several organisations concerned with the loss of cultural heritage in Syria, carrying out awareness campaigns and digitisation projects in the hopes of preserving as much as possible. Though this story focuses on the Second World War, it's important to note that there's a history of cultural preservation efforts in war, before and since.

'The idea of preserving cultural treasures during war was first formalised in the United States during the Civil War by President Lincoln to avoid deliberate destruction of cultural treasures during combat. It was further addressed in the Hague convention in 1907,' says Robert.

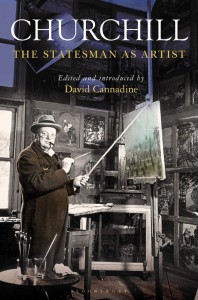

Though the work of the Monuments Men was carried out on the European mainland, UK institutions were also carrying out similar work in anticipation of bombing. The Director of The National Gallery at the time, Kenneth Clark, oversaw the safe evacuation and storage of all of the gallery's paintings. The collection was first stored in locations around Wales before being hidden in caves. Clark had approached Winston Churchill about sending the artworks to Canada by ship, but it was deemed too risky.

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery (1887–1976), 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, GCB, DSO

1952

Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969)

One can imagine that the priorities of museum professionals and archivists were at times at odds with that of the military. The Monuments Men initially experienced some resistance, but it certainly helps your cause when the Supreme Allied commander has an interest in art. General Dwight D. Eisenhower went on to produce over 250 paintings during his life.

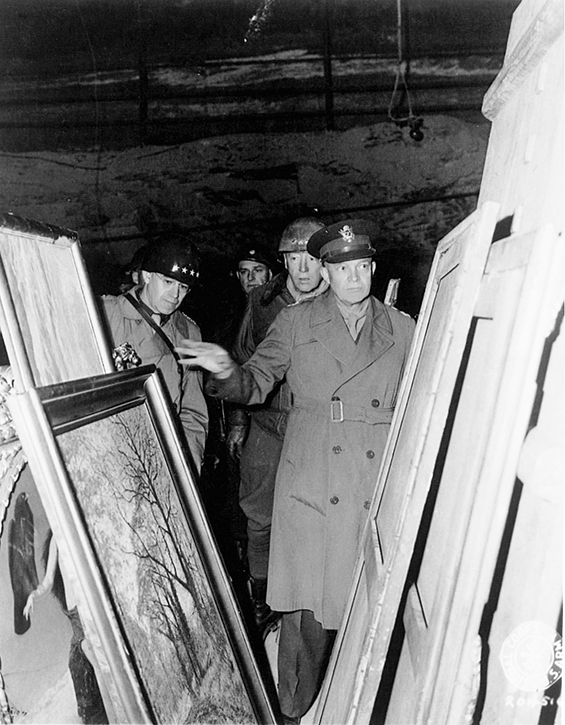

Merkers, Germany – 12th April 1954

Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley, Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr., and General Dwight D. Eisenhower inspect the German museum treasures stored in the Merkers mine. Also pictured in the center is Major Irving Leonard Moskowitz.

'[Eisenhower] made this a priority and he was supported in that effort by General Marshall, the Chief of Staff of the Army, and President Roosevelt, who approved the original plan that created the Monuments Men,' says Robert.

Race Institute Building – July 1945

'In a corner of the basement were hundreds of Torah scrolls piled ten-feet high. The Race Institute was used by Alfred Rosenberg to research the characteristics of various people overrun by the German Army and under subsequent Nazi rule. American Chaplain Samuel Blinder examines a Sefer Torah as he begins the overwhelming task of sorting and inspecting.'

Preservation efforts happened on a larger scale, including targeted bombing to avoid important buildings, but work was also carried out to protect smaller, more portable items. Many private citizens took it into their own hands to help protect and identify cultural objects. This was essential because, even as the Allied armies were closing in on the Nazis, they were attempting to smuggle paintings and objects into Germany.

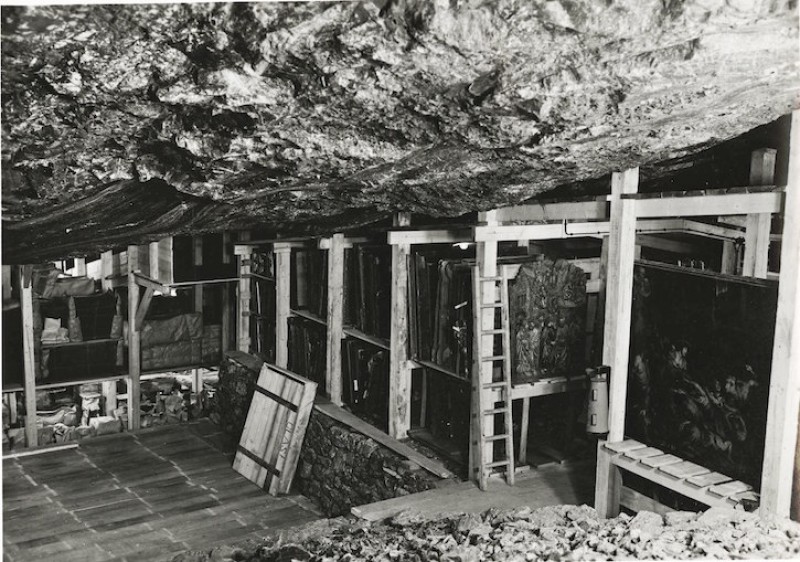

Altaussee, Austria – 10th July 1945

Removal of priceless works of art from the salt mine at Altaussee posed problems for Monuments Man George Stout unlike any ever contemplated. Stout constructed a pulley to lift Michelangelo’s 'Bruges Madonna' onto the salt cart to begin its long trip home to Belgium. Visible on the far left is Monuments Man Steve Kovalyak, an expert in packing art, who was a key assistant to Stout.

'They stole [the Madonna of Bruges by Michelangelo], got it on a ship and took it around the North Sea into Germany and then hid it in a salt mine,' says Robert.

The work of the Monuments Men didn't end with the war. Someone had to stay behind to organise and return an estimated five million stolen cultural objects, and there was no better-suited team. The operation was finally shut down in 1951 after the Army began to pull resources from the programme and focus turned to the Cold and Korean Wars. The team didn't want to abandon the project because they knew that there were still hundreds of thousands of missing objects, but fortunately, their work continues on. The Monuments Men Foundation continues this work and has found and returned more than 30 objects.

Paris – 2nd December 1942

At the Jeu de Paume Museum, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, painting in his left hand and cigar in his right, sits gazing at two works by Henri Matisse being supported by Bruno Lohse. Standing to Göring’s left is his art advisor, Walter Andreas Hofer. Note the bottle of champagne on the table. Both paintings were stolen from the Paul Rosenberg collection by the Nazis and were recovered and returned after the war. The painting on the left, 'Marguerites', today hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago. The other, 'Danseuse au Tambourin', is at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California.

'This is not a story about a dead subject matter of World War II history. It is a story... we continue to write the final chapter,' says Robert. 'As we find these things, they reveal elements of World War II that we often times didn't know [and] they open the door to other things that are missing.'

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes

.jpg)