Artis Lane (née Shreve) is a North American fine artist whose range of work spans from paintings of musicians and Hollywood celebrities, such as Stevie Wonder and Cary Grant, to busts of Black American icons, like Rosa Parks and Sojourner Truth.

Artis Lane with her sculpture of Rosa Parks

Born in 1927 in Ontario, Canada, Lane was raised just two hours' drive away, in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She began cultivating a passion for painting as a teenager and, as a young woman, she soon flourished in the craft after moving to Detroit, the epicentre of Black music at the time.

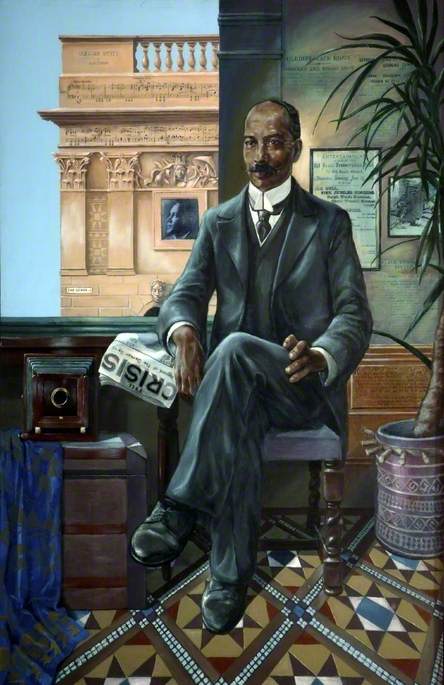

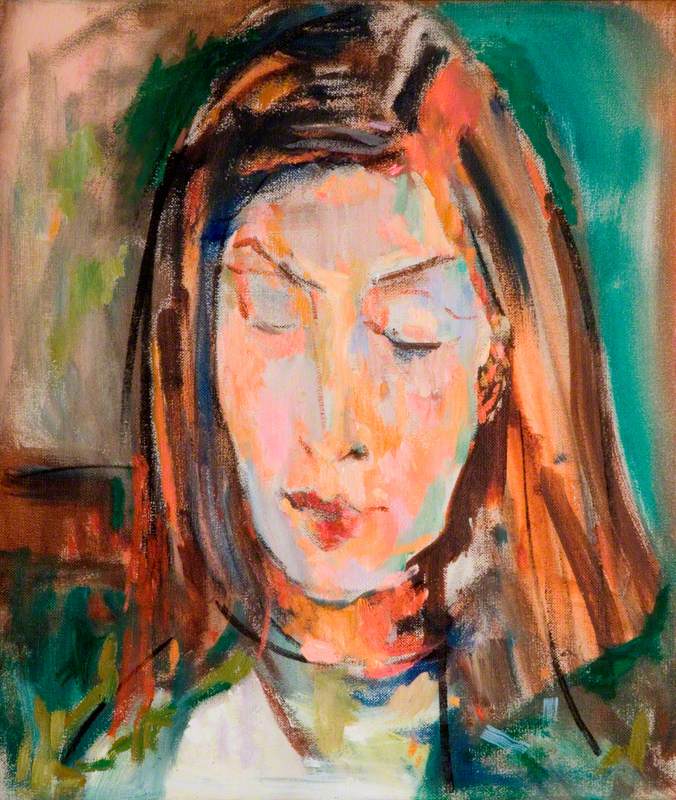

As of October 2021 on Art UK, there are merely five (of the 50,000+ total artists) under the 'African-American' nationality search category. With only two of the five artists alive today, Lane's 1977 painting of Her Imperial Highness Princess Ashraf Pahlavi of Iran (1919–2016) seems oddly misplaced. Hers is a well-defined portrait of a woman, while the others depict stylised scenes of collective Black life. And where the others feel weighted by context and history, Lane's stroke patterns convey an energetic and playful demeanour to the seated figure. Pahlavi donated this piece to Wadham College, Oxford.

HIH Princess Ashraf Pahlavi of Iran (1919–2016), Honorary Fellow

1977

Artis Lane (b.1927)

In a quest to understand how Lane's work has changed over time, I asked her to describe her career as a Black female artist, as well as to offer advice to a burgeoning group of global 'artivists', who aspire to follow in her footsteps. During the UK's Black History Month, the 94-year-old shared insights into her unique blend of artivism, which has allowed her to be a successful transnational Civil Rights contributor and a world-renowned fine artist.

Nafeesah Allen: You are Canadian-born but deeply active in the US Civil Rights Movement. Can you share how that connection happened for you and if it continues today? What are your thoughts on the globally interconnected nature of Black people's equality movements around the world?

Artis Lane: I am Canadian-born because my ancestors were anti-slavery abolitionists. They fled the United States to the British territory 170 years ago to continue their political work in safety. As a child it was ingrained in me by my grandfather to be upright and active in providing service to the community. I have sought to continue their social justice legacy through my art. I believe Black people's equality movements are obviously related.

Artis Lane and Rosa Parks standing next to Lane's sculpture and painting of Parks

Nafeesah: In 2009, yours was the first statue in the US Capitol to represent an African-American woman and your sculpture of Rosa Parks is housed at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC. Your most famous works are associated with the US Civil Rights Movement (1954–1968), and Rosa Parks in particular. What was your relationship to both?

Artis: Mrs Parks was my female hero. We were friends because she believed, as I do, that we should meet conflict with love. Love is often seen as a weakness. It is not. It is stronger than hate. Hatred kills itself.

I completed works honouring Mary McLeod Bethune, Sojourner Truth, Dr Dorothy Height, Myrlie Evers-Williams, Julian Bond, etc. I painted Malcolm X (El Hajj Malik al-Shabazz) after his trip to Mecca.

Artis Lane and her Sojourner Truth sculpture

Nafeesah: On Art UK, your portrait of Princess Ashraf Pahlavi of Iran, twin sister of the last Shah of Iran, now in the collection of Wadham College is different from the Civil Rights Movement-related work you're best known for in North America. Can you share more about the subject and the process of painting this portrait? How did this piece get acquired?

Artis: I am not a sympathiser with any political affiliations my subjects may have. I approach them as God created them.

She and I felt we understood one another. I remember she asked me, 'What is a hippie?' She said her son had become one. We connected as mothers.

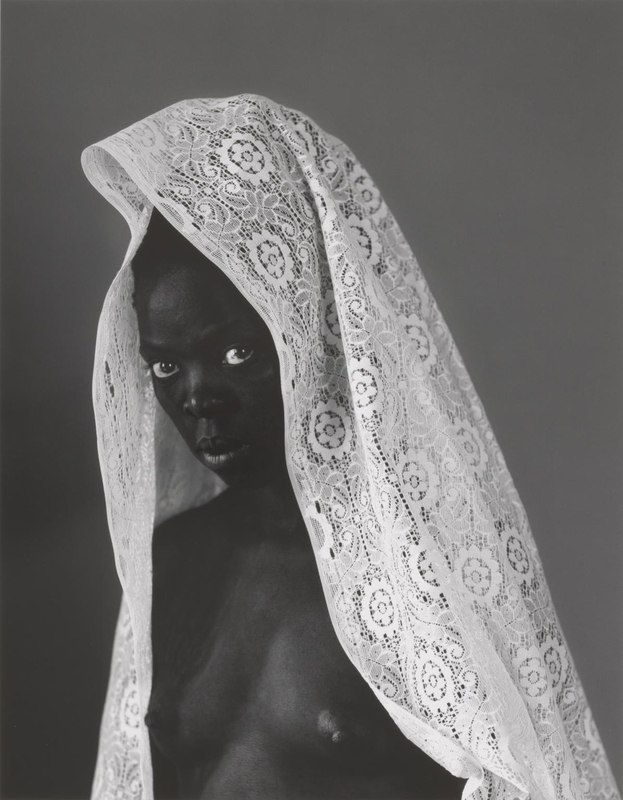

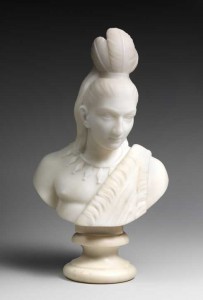

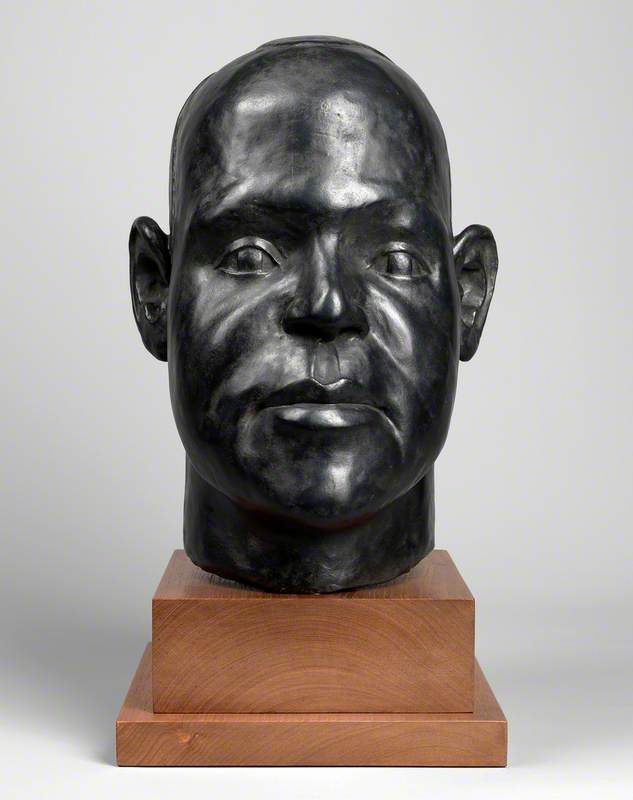

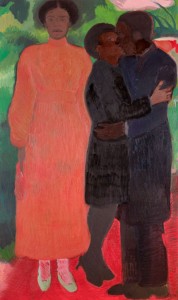

Emerging New Man

sculpture by Artis Lane (b.1927)

Nafeesah: What are the challenges that you faced as an arts activist? Do you recommend any coping or sustainability strategies for other working artivists, trying to make a living as working artists in markets where they and their identity-based issues are underrepresented?

Artis: I realised I needed to change direction with my work in the 1980s. I had been making a good living as a portrait artist for many years, but I wanted to get back on track as the fine artist I had intended to be from the beginning: a visual artist making strong statements.

When I was given the book Science and Health, I decided to create a series of sculptures to represent mankind's search for its source. I chose 'Generic Man' (a pure African from whom stems all races) to represent all mankind's journey toward truth. I studied under Jan Stussy to learn what was going on in painting. There is great value in continually challenging habits in the way you work. You learn new methods.

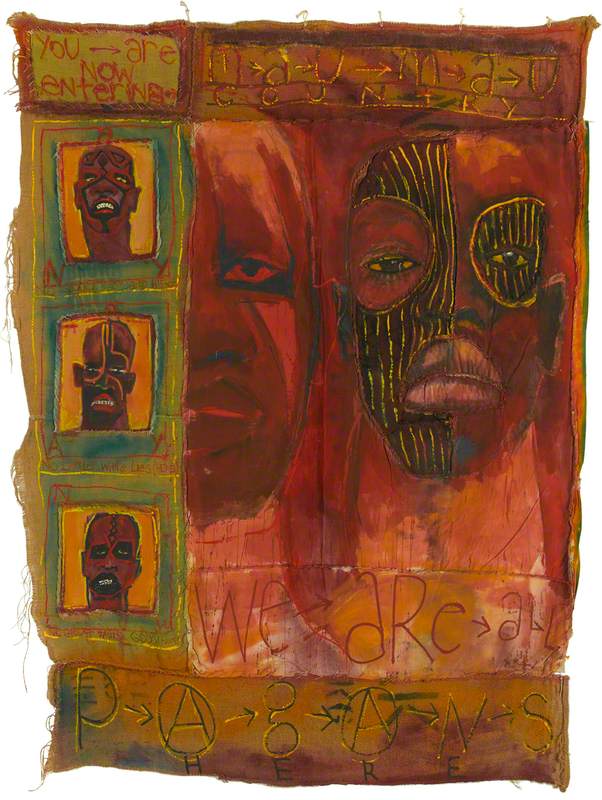

Wise Virgin

1989, mixed media by Artis Lane (b.1927)

I would recommend to artists that they periodically search within to see if they are still on the path that they were meant to follow. Recognise those soulful moments that are meant specifically for you.

Nafeesah Allen, writer