My own fascination with the role of refugee artists in Britain began in the 1990s through encountering some of the artists whose lives were changed by knowing the émigrés Josef Herman and Heinz Koppel, who both came to the South Wales valleys in the 1940s. Herman escaped to Belgium from the oppression of Jews and radicals in his native Poland in the 1930s and, as war broke out, ran ahead of the German advance across France and, in due course, got to Scotland and then to London.

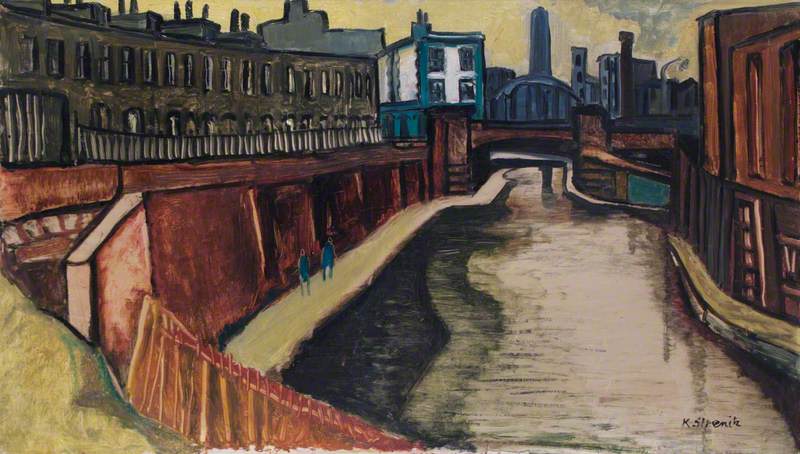

In 1944, he arrived in the mining village of Ystradgynlais almost by accident and felt so embraced by its community and landscape that he stayed for twelve years. In that time his fresh, expressionist eye changed public perceptions of the coalfield and inspired the work of younger artists.

Heinz Koppel left Berlin for Prague in 1933 and came to Britain in 1938. He influenced many young artists with his expressionist vision and artistic integrity. Like many other expressionists, however, his work confounded wider audiences in Britain – one Times review was headlined 'A Painter with Too Many Ideas'. After his studio in London was bombed, he moved to Merthyr Tydfil where he led a workers' educational settlement for more than a decade. He was later an influential teacher in Liverpool.

These two artists led me on to explore the careers and influences of émigrés from other periods. The resulting exhibition, 'Refuge and Renewal: Migration and British Art', at the Royal West of England Academy and MOMA Machynlleth, reaches back to Monet and Pissarro and up to the present day, and my accompanying book nudges the story back to Holbein and Eworth.

'Refuge and Renewal: Migration and British Art' by Peter Wakelin

The arrival of refugee artists has long been a force for inspiration and renewal in British art. Émigré artists have made contributions through their practice, teaching and personal influence. However, there have been times when crucial opportunities for renewal have been missed because émigrés stayed only a short time or British artists did not engage with them.

Artists have come to Britain as refugees from war, ethnic persecution or intellectual oppression. French painters and sculptors fled from conflict in 1870–1, Belgians escaped the destruction of the First World War, and, in the 1930s, artists escaped totalitarian regimes, most significantly in Nazi Germany. In the last 80 years, artists have come as refugees from the Soviet bloc, China, Latin America, the Middle East and elsewhere.

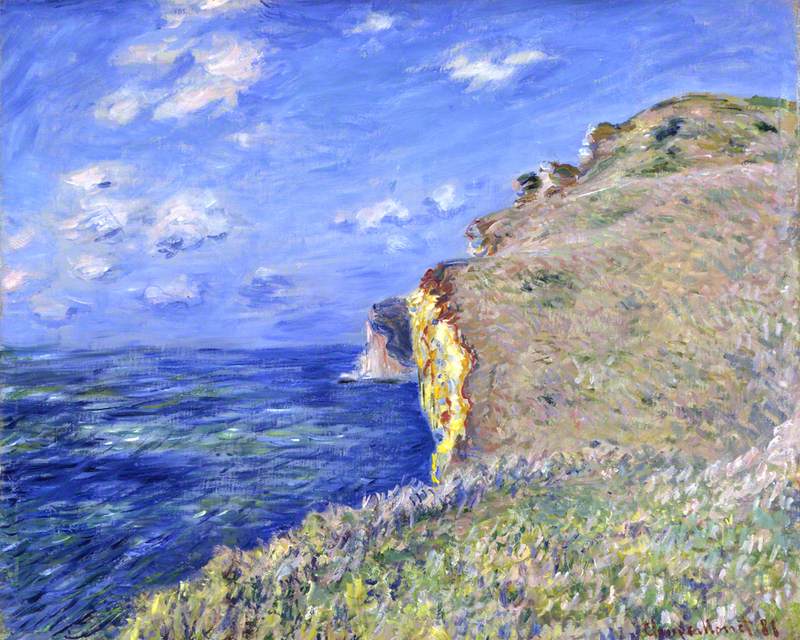

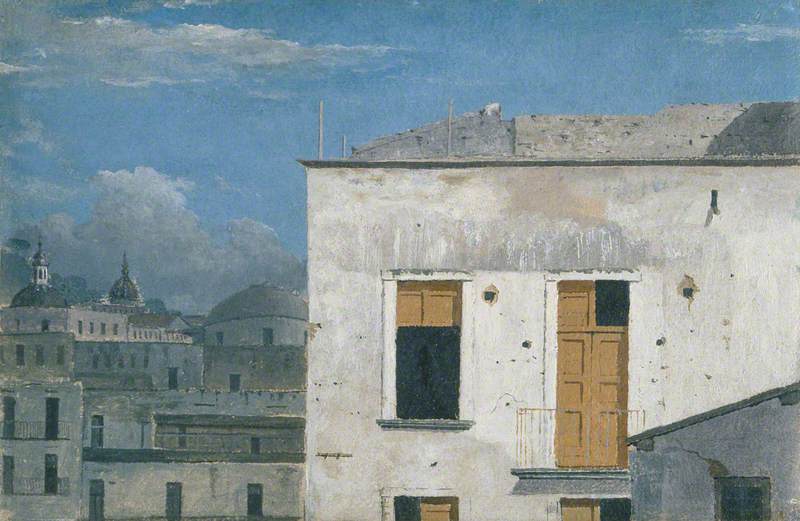

In 1870, London was teeming with artists from Paris due to the Franco-Prussian War and its aftermath, including Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro. At this time they were still developing the ideas behind Impressionism. In London, they committed themselves to painting outdoors and discovered affinities with the works of Constable and Turner.

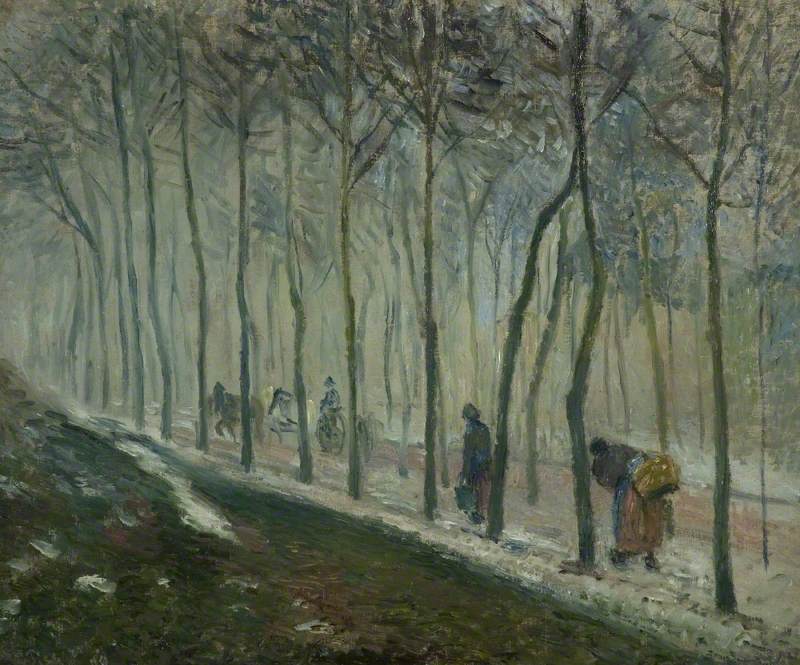

La route, effet de neige (The road, snow effect)

1879

Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

Monet loved to observe the activity of the Thames and its light effects. English taste was still dominated by the Pre-Raphaelites and he and Pissarro were both rejected from the Royal Academy summer exhibition. Monet said he would have starved in London if his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (who had also fled to England) had not sold some of his paintings. Largely ignored by British artists, the Impressionists' influence was not felt until long after they left, as Durand-Ruel gradually sowed the seeds for the dominance of Paris in British art for generations to come.

Pissarro had fled his home at Louveciennes because it was close to the Franco-Prussian fighting. He took his family to Brittany and then London. Some 1,500 paintings he left behind were destroyed, largely wiping out the record of his work up to the age of 40.

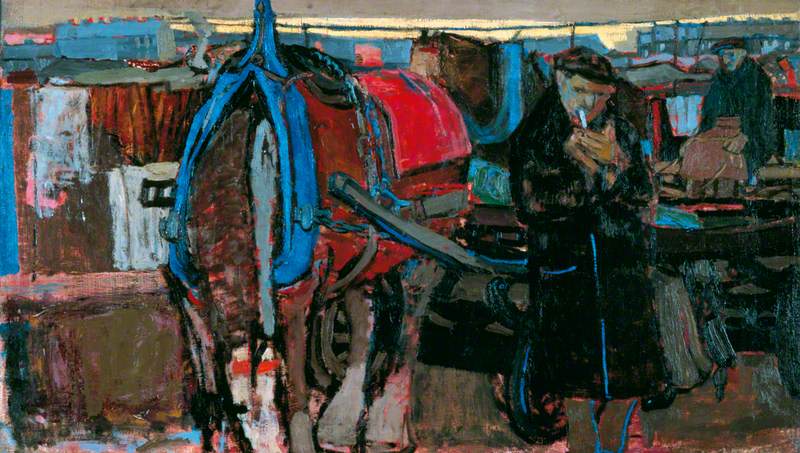

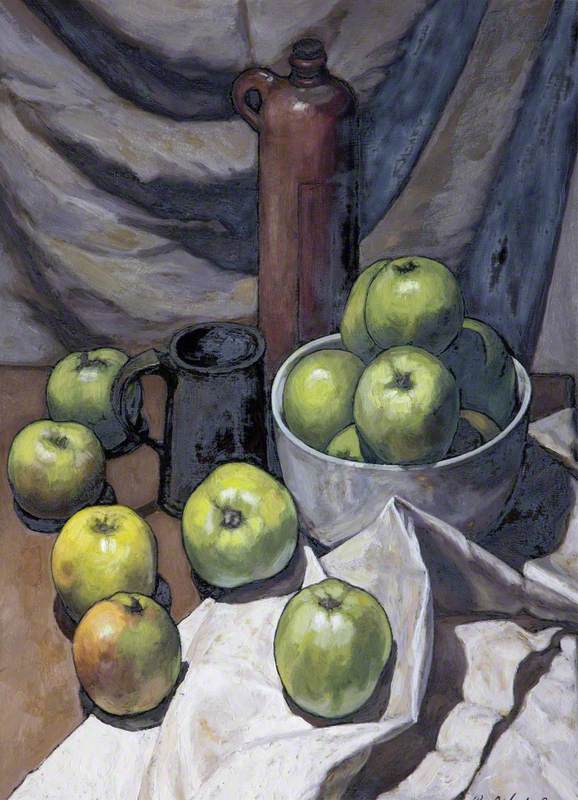

Pissarro's painting of French peasants bearing burdens through the snow echoes the desperation of the refugee, though it was painted in 1879, long after he returned home.

A few of the French artists did stay longer, particularly those who had been associated with the revolutionary government of the Paris Commune. The sculptor Jules Dalou became a political refugee in 1871. The new government tried him in absentia and sentenced him to life imprisonment. Nevertheless, in London he was appointed professor at the South Kensington School of Art and commissioned by Queen Victoria. His work exemplified a fluid naturalism he had developed with his friend Rodin since they were both teenagers. He returned to Paris following the amnesty of 1879 but his influence on the New Sculpture movement in Britain continued well into the next century.

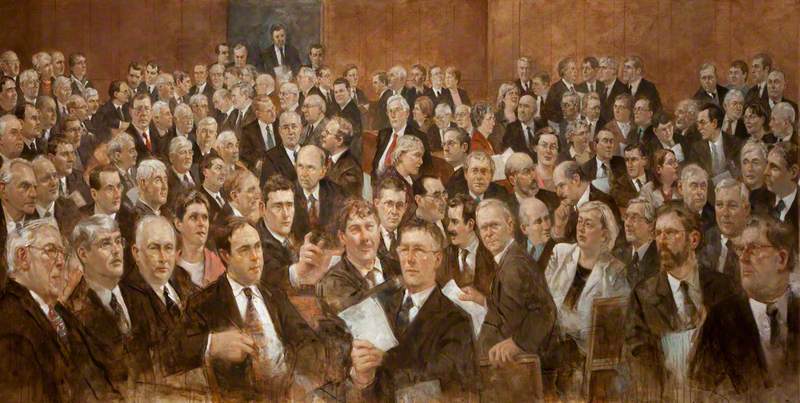

When 250,000 Belgian civilians arrived during the First World War, it was the biggest refugee movement in British history. About 60 artists were among them, including leading Symbolists such as the sculptor George Minne and the painters Constant Permeke and Valerius de Saedeleer. British patrons provided homes for many of the artists. Nevertheless, most felt isolated and in due course rebuilt their lives in Belgium, with opportunities for British artists to engage with them unfulfilled.

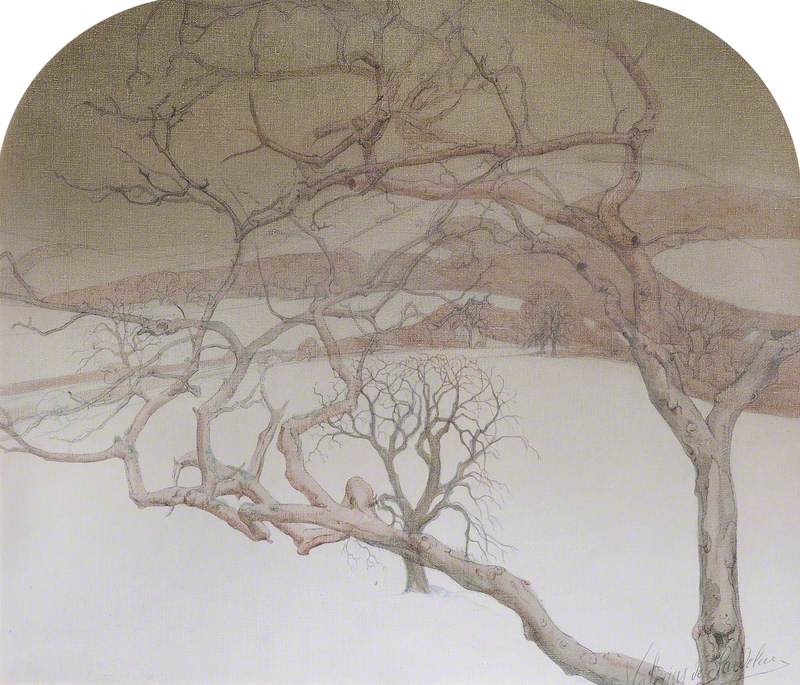

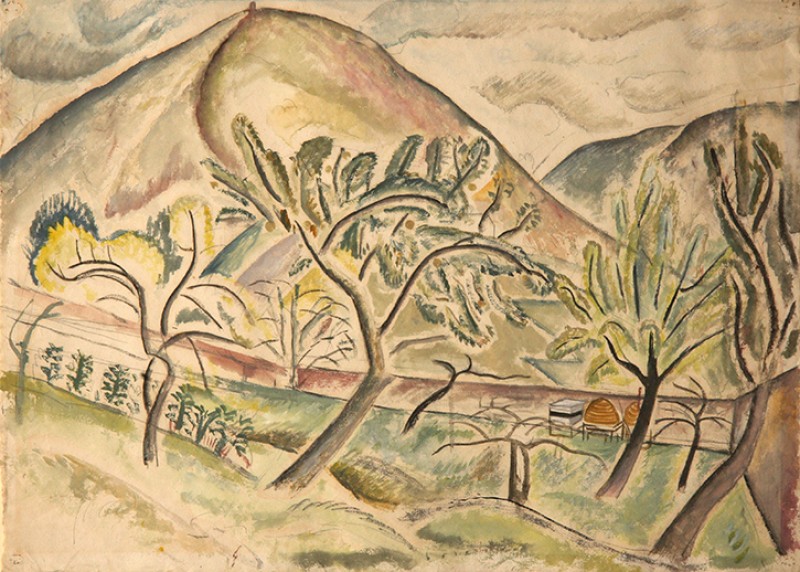

The Davies family of Llandinam found a house near Aberystwyth for the Symbolist painter Valerius de Saedeleer and his wife, five daughters and 90-year-old father. De Saedeleer's heightened, stylised paintings seemed foreign to people used to the British tradition of landscape. He met few other artists during his extended stay. He bartered paintings to pay for goods and found some commercial success with an exhibition in Aberystwyth, though a review in the local paper warned: 'he has the eyes of a primitive'. When he returned to Belgium in 1921 he named his new house 'Tynlon' after his Welsh wartime home.

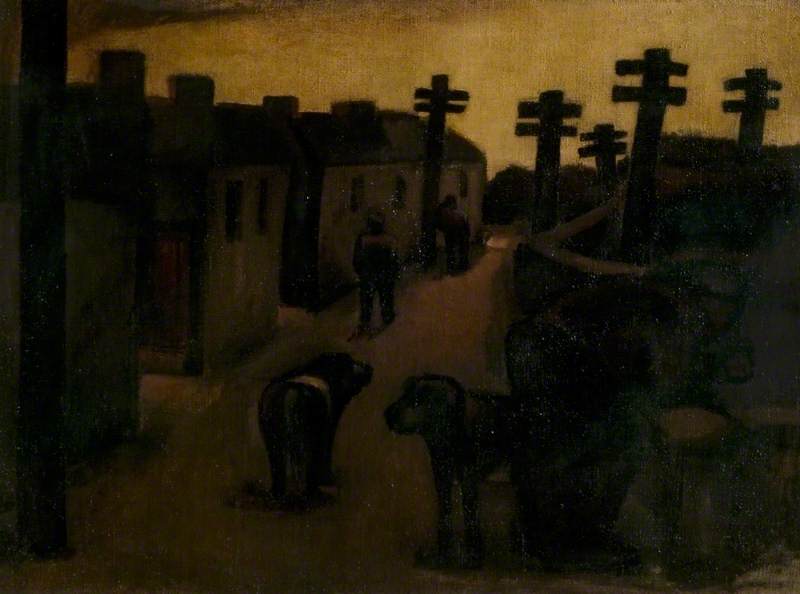

Constant Permeke was the exception among the Belgian exiles in developing a lasting reputation in Britain, though this was largely through his influence on the post-war development of Belgian expressionism. Permeke joined the Belgian army on the invasion and was severely wounded. He was evacuated to Folkestone and, reunited with his wife, moved to Wiltshire and then Devon, where he painted bold, primitive landscapes until he returned to Ostend in 1919.

His monumental depictions of the labours of farmers and fishermen influenced many artists, including Josef Herman, who was helped by him when fleeing Poland in the 1930s.

By contrast with the Belgians who remained only a short time, the French artist Lucien Pissarro was to have a profound effect on British art. As a child, he had fled the Franco-Prussian War with his father, Camille. He returned to Britain two decades later as a visitor rather than a refugee and met and married his English wife. However, the First World War made him decide to take up citizenship. His first-hand knowledge of the Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists powerfully influenced the Camden Town Group: Spencer Gore called him a 'fountain of true principles' and Walter Richard Sickert acknowledged that Pissarro had made him observe colour in shadows. His view across a Wiltshire village, from the year he became a citizen, seems to celebrate Englishness and distance from conflict.

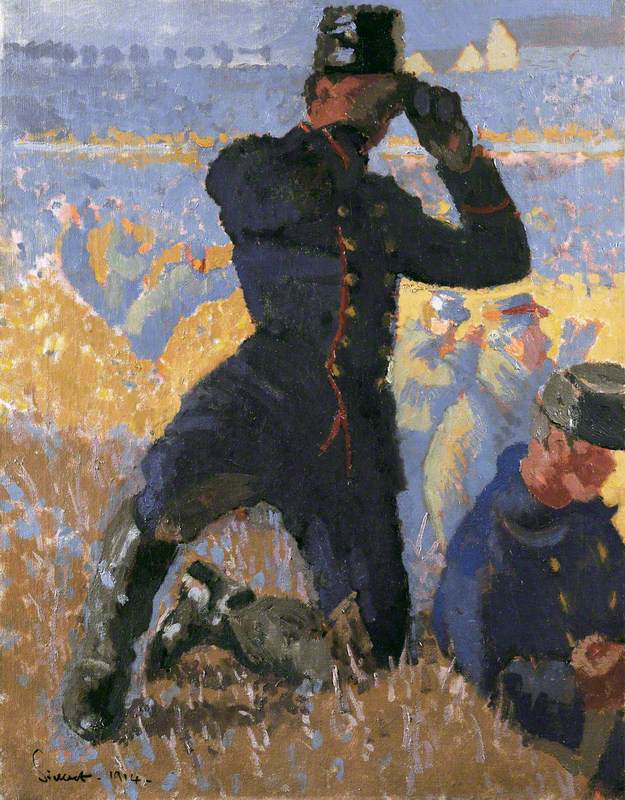

Sickert knew the insecurity of exiles trying to re-establish themselves in a new country, as he himself had come to Britain as a child refugee. He painted The Integrity of Belgium in 1914 to sell in aid of the Belgian Relief Fund and – as its title suggests – in tribute to the soldiers who defended Liège. He found soldiers to pose for him and borrowed uniforms from London hospitals where the wounded had been taken. The alert figure with field-glasses represents the courage of his countrymen, entrenched behind him in the misty plain.

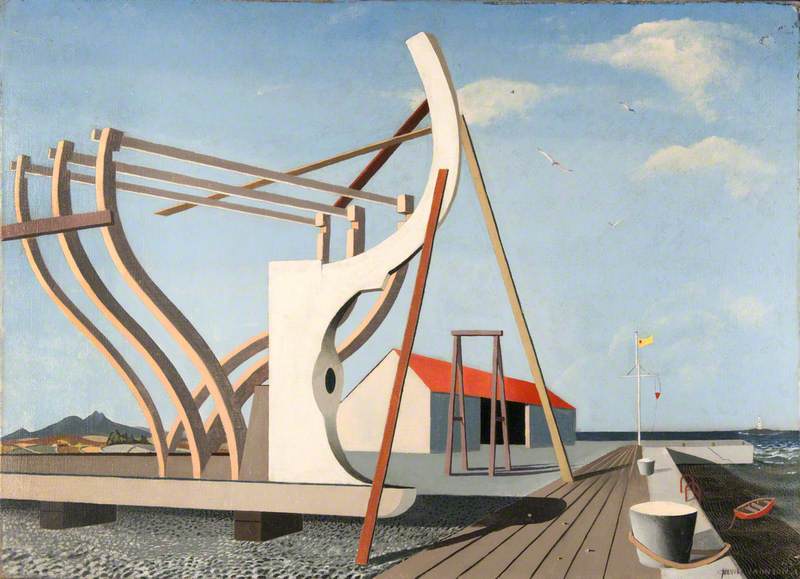

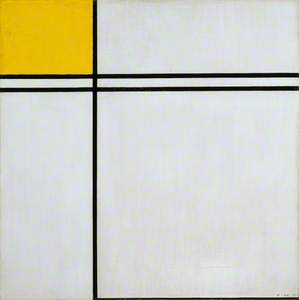

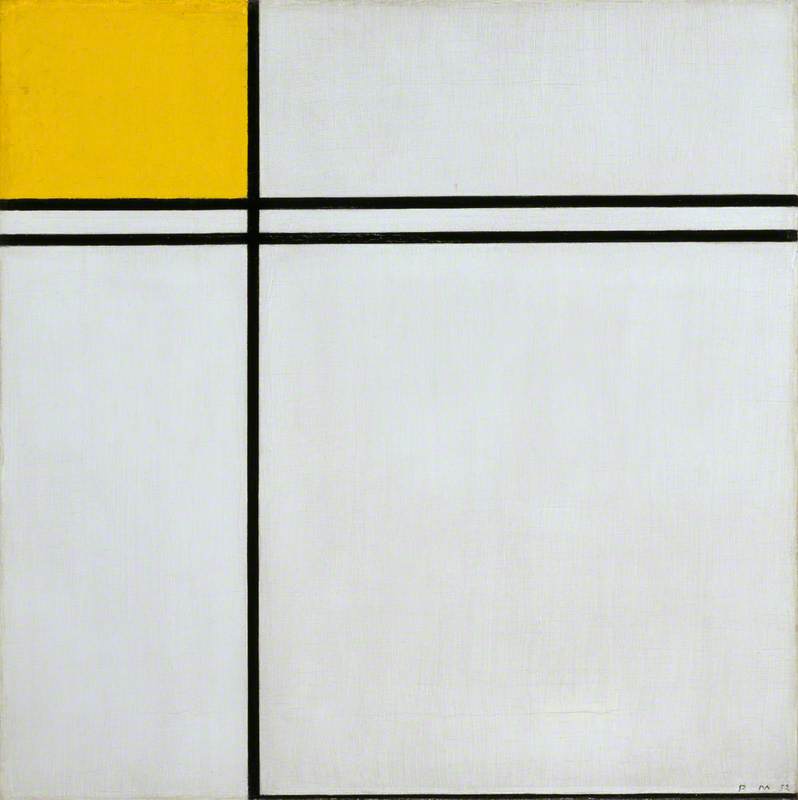

Composition with Double Line and Yellow

1932

Piet Mondrian (1872–1944)

The surge of totalitarianism and racism in the 1930s drove thousands of people to flee Austria, Germany, Poland, Russia and other countries. In Germany, the Nazis recognised art as a powerful force that they needed to control. Artists they regarded as modern in style, different in politics or racially 'non-Aryan' were labelled 'degenerate' and forbidden from working. Many saw their work confiscated or destroyed and some were beaten, intimidated or imprisoned. Around 200 artists from Germany and the countries it annexed or invaded were murdered in the Holocaust.

Between 1933 and the Second World War some 300 artists came to Britain. They had more impact than the émigrés of the preceding generation for several reasons: they were supported by the art community, many of them were committed to making their work relevant and most stayed for the rest of their lives. Through their personal interactions, art and teaching they inspired fresh thinking about expressionist painting, constructivism, documentary photography, animation, public sculpture and graphics.

Painters such as Piet Mondrian, Jankel Adler and Josef Herman, the sculptor Naum Gabo, documentary photographers such as Bill Brandt and Felix H. Mann and the animator Lotte Reiniger influenced some of the most important British artists of the mid-twentieth century.

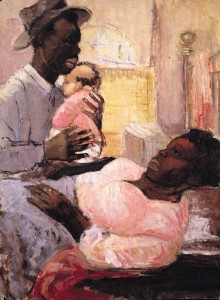

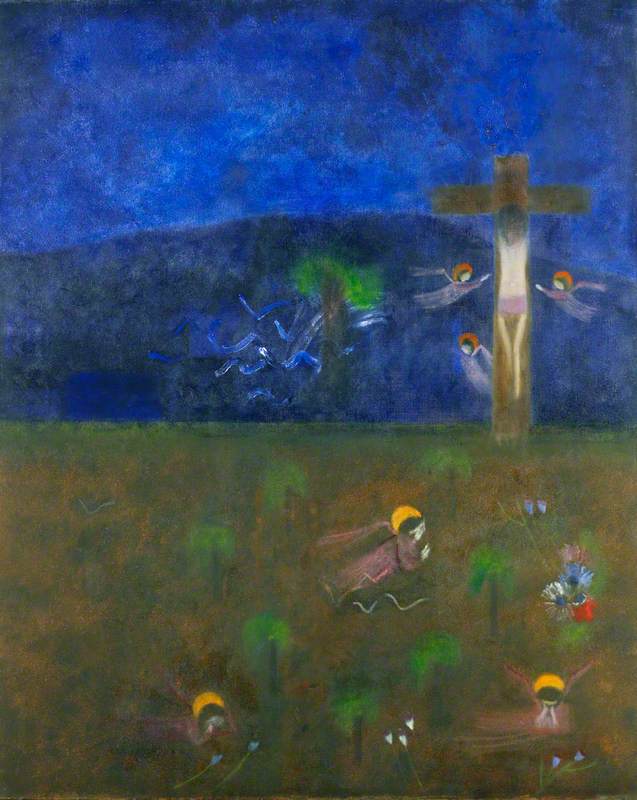

Josef Herman was a mentor for several artists, including Will Roberts in Wales and before that, in Glasgow, Joan Eardley. Eardley met Herman as soon as he arrived in Glasgow in 1940, when she had just started as a student at the School of Art. They saw one another frequently for three years. Her expressive, strongly coloured paintings of children and workers in the Glasgow tenements echo his bold style and his commitment to working life and labouring people.

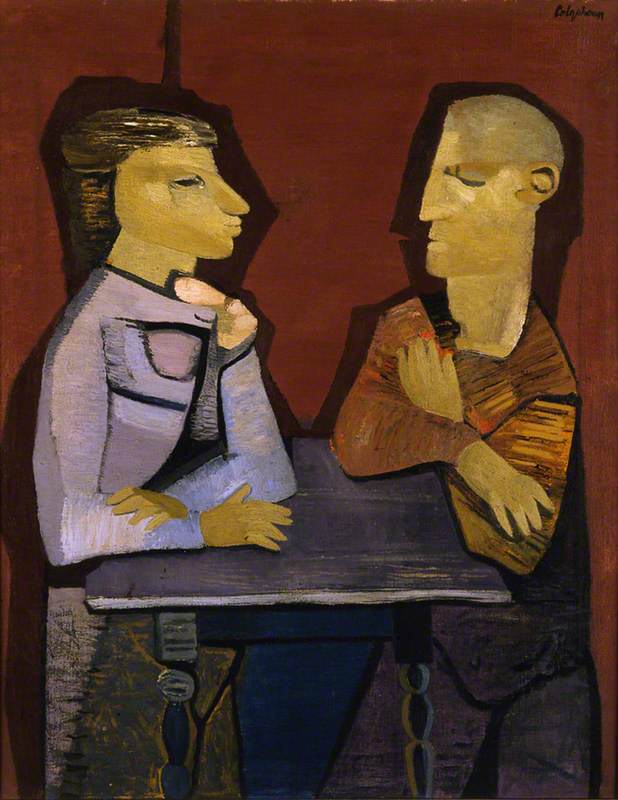

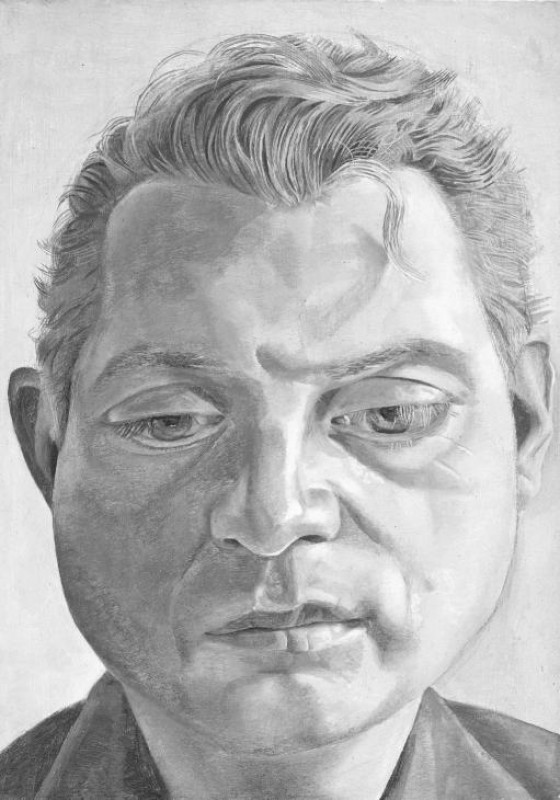

Two of the outstanding British painters of the mid-twentieth century, Robert Colquhoun and his partner Robert MacBryde, were linked to European modernism by the Polish artist Jankel Adler. They met him in Glasgow and from 1943 shared a house and studios in London. Both referred to him as 'the Master'.

Their painting almost immediately took on similar characteristics: their choice of figure subjects, expressive use of colour and flattening of forms as they shifted from a British neo-romanticism to a more European style.

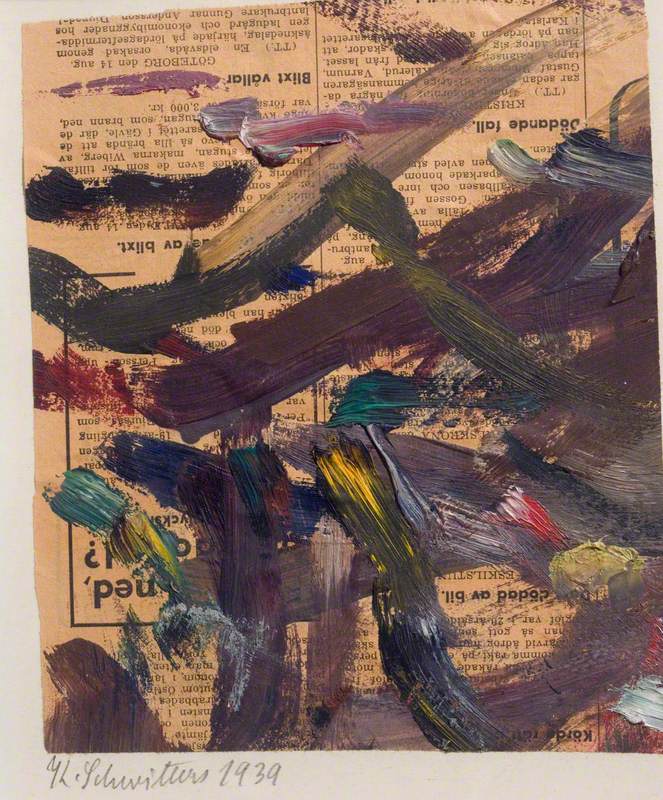

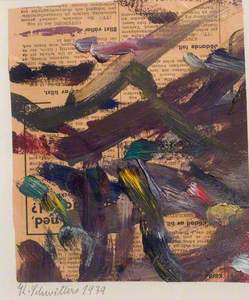

Although Kurt Schwitters was to become a vital influence on Pop Art, Conceptual Art and installation art he was almost unknown in Britain in his lifetime. He began his Dadaist collages called 'merz' or 'rubbish' after the First World War. He was interned on arrival but completed up to 300 pieces with found materials. After release he lived in hardship in the Lake District until he received a stipend from MOMA in New York to build his 'Merzbarn', a recreation of his innovative collage environment first created in Germany in the 1930s. He died the day after he was granted British citizenship in 1948.

Inevitably, many artist refugees of the era remained much less known and appreciated. Else Meidner was encouraged to study art by Käthe Kollwitz and had a solo exhibition in Berlin in 1932. She came to London with her husband, the German expressionist Ludwig Meidner, in 1939. They lived in poverty: he became a mortuary attendant and she a domestic servant. After the war, like most Jewish artists she found it inconceivable to return to Germany in full knowledge of the Holocaust. Nevertheless, Else Meidner said 40 years after arriving: 'Here in London I walk about as in a dream and am surprised I'm here. Some plants thrive wherever you transplant them, but I could never put down new roots. My roots are in Berlin.'

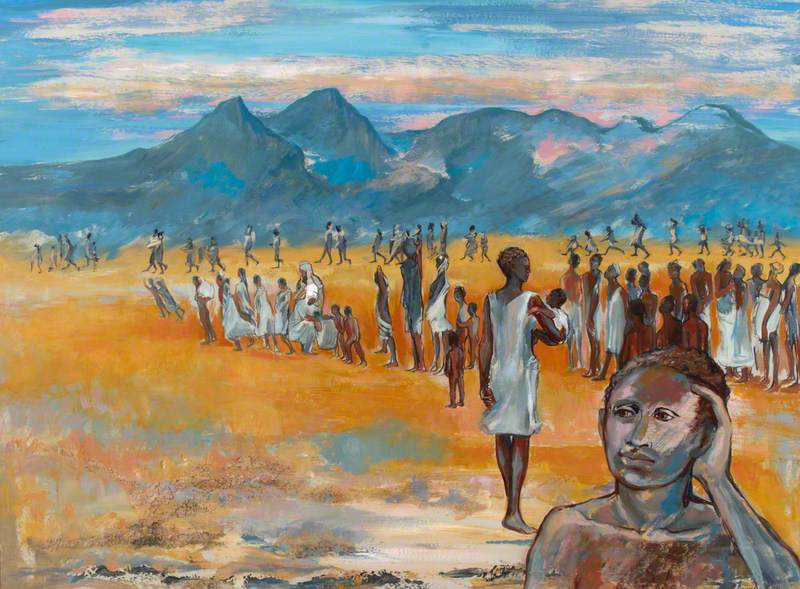

Since the Second World War, although international cooperation has advanced peace and human rights in western Europe, conflict and persecution have arisen in many places. In the last 75 years, artists have fled to Britain from China, countries behind the Iron Curtain, dictatorships in South America and Africa and wars in the former Yugoslavia and the Middle East. Among the artists forging careers in Britain now are Humberto Gatica from Chile, Hanaa Malallah and Walid Siti from Iraq, Zory Shahrokhi from Iran and Samira Kitman from Afghanistan. Mona Hatoum, born in Beirut, has become one of the most influential British artists of her generation.

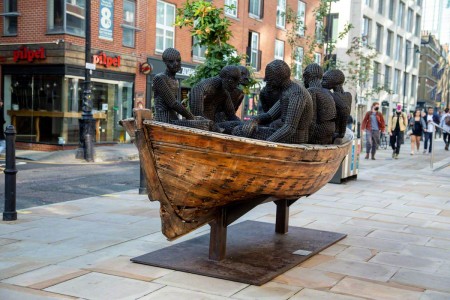

New emergencies can ignite suddenly and devastatingly. Recent asylum-seekers have escaped the atrocities of IS, ideological persecution in Iran and Afghanistan and war in Kurdistan. The total of people displaced worldwide is at an all-time high of 70 million. The great majority remain in their own or neighbouring countries but Britain has offered refuge to a small number.

Contributions to British culture are being made by artists who have come here as refugees or as visitors unable to return home. Often, they record their experiences of statelessness, war or oppression. Some express memories of the homes they had to leave behind or continue to practise with traditional forms and sensibilities from other cultures. The impact of these recent migrants is still unfolding.

Peter Wakelin, writer and curator

The exhibition 'Refuge and Renewal: Migration and British Art' is at the RWA Bristol from 14th December 2019 to 1st March 2020, and at MOMA Machynlleth from 14th March to 6th June 2020

Refuge and Renewal: Migration and British Art by Peter Wakelin is published by Sansom and Company