Open to the public since 1991, The Fan Museum is the UK's only museum entirely devoted to the multifaceted history, culture and craft of the fan. Small-scale, independent and situated within the World Heritage Site of Greenwich, a pair of Grade II* listed Georgian period townhouses accommodate the Museum. Its ever-expanding collections are gathered from across the world and encompass more than 1,000 years of fan artistry.

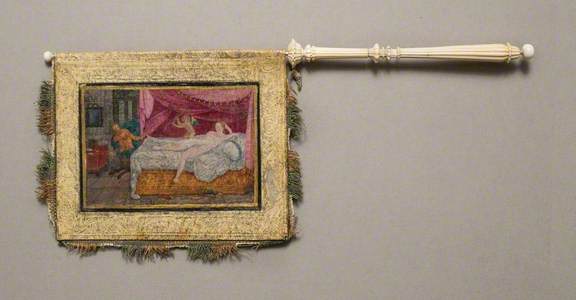

Venus, a Satyr and Cupid – Cupid Trapping Birds

c.1590

Raphael Sadeler II

Amongst the Museum's earliest and therefore rarest treasures is a late-sixteenth-century flag fan, a miraculous survival from a time when handheld fans were carried mainly by royalty and the nobility. It was probably manufactured in Venice, Italy where flag fans (in Italian, ventarola) enjoyed popular status throughout the sixteenth century. Demonstrating fine craftsmanship throughout, a fan of this type served a practical purpose – the 'flag' spun around the handle, conjuring a cooling breeze – but also signified the elite status and aesthetic taste of its possessor.

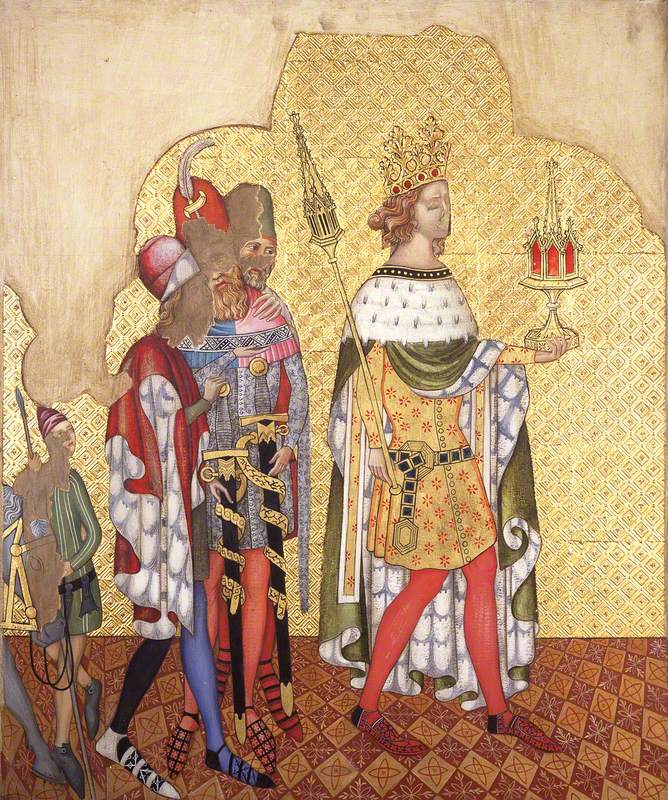

Fan Commemorating the Restoration of Charles II

c.1660

unknown artist

In the latter part of the sixteenth century, folding fans (a Japanese invention) came into fashion in the West and among the Museum's earliest examples is one made to commemorate the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy under Charles II in 1660. Emblazoned with a woodcut print, the paper leaf features a medley of patriotic motifery including crown jewels, oak leaves and curling ribbons inscribed 'The Hapy [sic] Restoration'. In the immediate aftermath of the Restoration all kinds of decorative wares were available to purchase and the unfurling of this overtly political costume accessory in Royalist company would no doubt have been warmly received.

Other important fans in the collection with regal associations include one made to commemorate the wedding in 1770 of the Arch Duchess Marie-Antoinette to the Dauphin of France (future King Louis XVI). Portraits of the ill-fated newlyweds occupy the centre of the leaf, flanked on either side by their respective coats of arms: the double-headed eagle symbolising Marie's Austrian family (the House of Hapsburg) and for Louis, fleur-de-lis and dolphins.

Marriage of the Dauphin Louis and Marie-Antoinette

1770

unknown artist

The Royal couple's wedding fan was manufactured in the eighteenth century, a period widely referred to as the fan's golden age, when the craft of fan-making reached a zenith and the carrying of fans throughout Europe was especially prevalent.

Testament to the ingenuity of the eighteenth-century artisans involved in the production of fans is one which incorporates, at the pivot end, a key-wound timepiece by a London-based Huguenot watchmaker named John Thierry. Held closed, as fans often were, a novelty such as this would have attracted admiring glances and proved something of a conversation starter.

For those unable to splurge on costly bejewelled and hand-painted confections, inexpensive fans incorporating paper leaves decorated with mass-produced etchings, sometimes enlivened with splashes of watercolour paint, were available to purchase from the early eighteenth century onwards.

Among The Fan Museum's most popular treasures is a so-called 'mask fan', its leaf printed with a series of puzzling vignettes including a woman brandishing a cat-o'-nine-tails with which she vents her fury upon a cowering man. Occupying the central part of the design is a masklike face cut with peepholes, enabling the person carrying the fan to conceal their identity whilst observing their immediate surrounds. Although its intended use remains unclear, the assumption is that mask fans, of which only a handful are known to survive in museum collections around the world, were made to be carried at masquerades and carnival.

Toward the end of the eighteenth century, fans went into decline and would not fully return to fashion until the second half of the nineteenth century. The 1850s ushered in a period of prosperity in Europe, especially in France where Napoleon III's rise to power was celebrated with a series of sumptuous balls referred to as Fête Impériale. At these lavish, elite social occasions, Eugenie, Empress of the French and her retinue of attendants held Court, wearing custom-made gowns by Frederick Worth and carrying equally magnificent folding fans.

One such fan held within the Museum's collections formerly belonged to the Empress, her coat of arms – incorporating the Napoleonic Eagle – visible on the reverse side. The public-facing side is finely painted with an eighteenth-century pastiche (Eugenie is known to have revered Marie-Antoinette) showing figures bathing in the restorative waters of a mythical Fountain of Youth.

The Empresses' fan was manufactured by maison Alexander, the preeminent fan-maker active in France during the second half of the nineteenth century. Information about Alexandre (Felix Pierre Victoire) is scant: in 1849 he established his Company and drew together a coterie of talented craftspeople and painters (many of whom exhibited their works at the Paris Salon) who together elevated the craft of the fan to unparalleled heights. He and other leading fan makers of the period vied for the patronage of Europe's crowned heads and re-established aristocracy and did so by manufacturing ever more opulent statements of artistry.

Epitomising this fashionably lavish style of fan is one with sumptuous tortoiseshell sticks and guards expertly carved to resemble the rays of the sun and set at the pivot end with a diamond-studded, star-shaped silver pin. Its leaf opens to a span of a semi-circle, a fittingly largescale canvas for a theatrical painting by Gustave Lasellaz of a female figure in flowing drapery hovering in a clouded night sky twinkling with stars, some of which are studded with real diamonds – a fan surely designed to wow rather than simply cool!

Before fans went almost entirely out of fashion following the Great War, there would be time for a final flowering of artistic brilliance commensurate with the Edwardian period.

It's from this moment in time that some of The Fan Museum's most striking fans date, including an outstanding Art Noveau confection, its silk leaf finely painted with peacock feathers and Byzantine princess, her flowing locks framed by an intricate, jewelled headpiece. The fan's mother of pearl sticks, skilfully worked by a renowned fan stick-maker named Georges Bastard, are tinted shades of turquoises and blue and whipped into feather shapes to add emphasis to the Art Nouveau stylings of the leaf; the whole effect is both breathtakingly beautiful and surprisingly modern.

Bastard was born into a family of tabletiers (his Grandfather won a medal at the 1867 Paris Universal Exhibition for a set of fan sticks) who specialised in the production of broad-ranging wares including decorative objects such as fans and chessboards, dominoes, buttons and combs.

Contrary to the conventions associated with the discipline of fan painting are several 'works' in the Museum's collection by celebrated fine artists and illustrators such as Gustave Doré who, around 1870, painted onto a folding fan a dramatic rendering of Love vanquishing Evil.

Featuring warring putti, beasts and other grotesques, the freely painted composition is reminiscent of illustrations the artist made for an 1861 edition of Dante's epic poem the Divine Comedy and may allude to the sufferings endured by France in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian war (1870–1871). Doré, a fervent patriot, was deeply affected by the conflict and made numerous works in response to it.

Don Quixote and Sancho Panza

1978

Salvador Dalí

An artist whose notoriety far exceeds that of Doré is the Spanish-born surrealist, Salvador Dali who in 1976, aged 73, decorated a mass-produced folding fan with a felt-tip sketch of characters from Miguel de Cervantes' sixteenth-century literary masterpiece, Don Quixote.

Jacob Moss, Curator at The Fan Museum