Basil Blackshaw's reputation as one of Ireland's foremost painters of authentic rural life is well deserved, but the length and breadth of his career reveal so much more about this quietly disruptive artist.

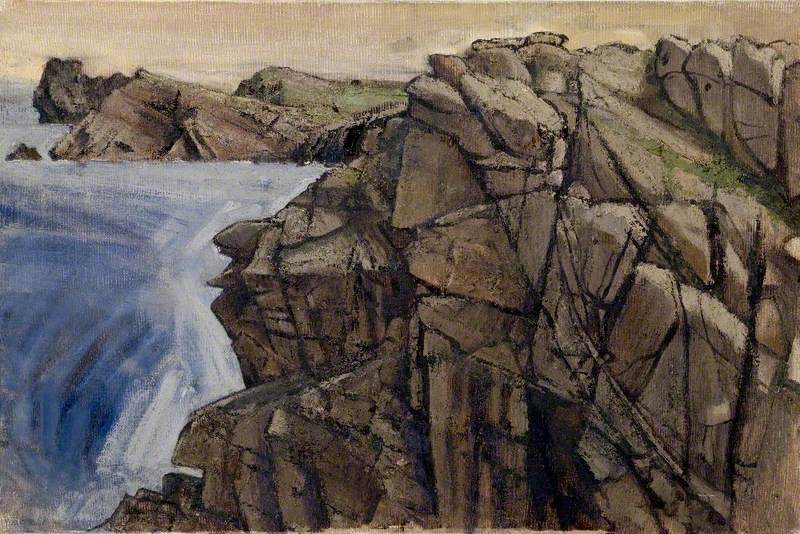

He started off painting the things he knew: domestic animals, birds, dogs and horses, shown as working animals, in states of rest or on the cusp of moving, such as Fighting Cock, although not often at play. County Antrim landscapes, the surrounding hills and the Lagan Valley all provided ample inspiration, however the localism of his themes belies the sophistication of the result.

The artist's upbringing, centred on a rural society of horses, hunting dogs and 'doggy men', gave him a familiarity with and understanding of these animals and people which cannot be taught or studied. Along with his observational skills and keen eye for form and colour, this provided the foundation for his career which saw success from a young age.

Blackshaw entered the Belfast College of Art aged just 16, meeting his fees with his earnings from horse portraiture. He was one of a group of other significant northern artists at this time, including Cherith McKinstry (née Boyd) and T. P. Flanagan. Contemporary influences included Dan O'Neill, George Campbell and Gerald Dillon: 'They opened our eyes as students because we only knew what was in the museum more or less, the modern collection, and these boys were painting in a completely different way.'

Like Seamus Heaney, whose 'roots were crossed with [his] reading', Blackshaw reimagined the personal experiences he had growing up in rural Northern Ireland through the prism of his interest in European art and painters like Cézanne, Degas and Manet.

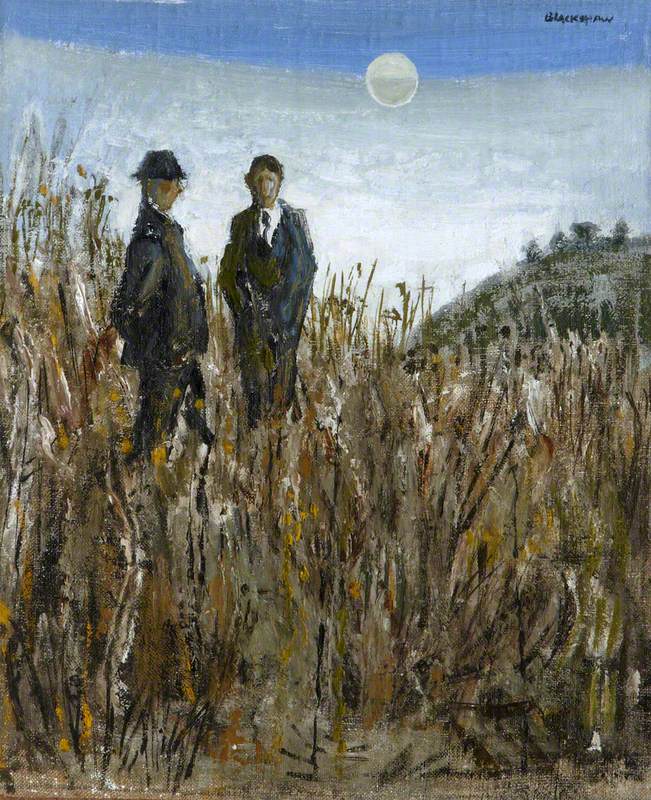

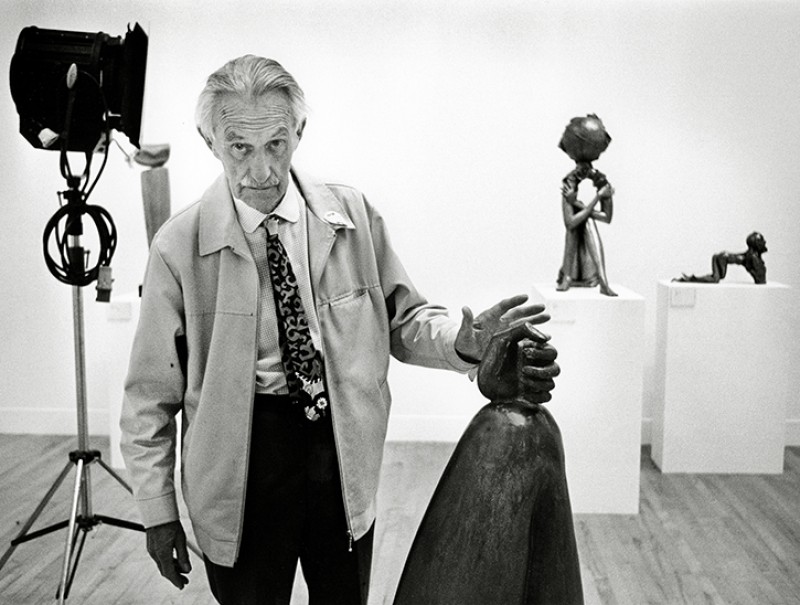

In 1955, aged only 22, he became one of the youngest artists ever to be invited by the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery, now the Ulster Museum, to present a one-man exhibition. He showed 36 paintings and was praised as 'an Ulster painter of serious and considerable promise' in the Belfast Telegraph. John Hewitt, writing under the pseudonym MacArt, paid particular attention to The Cornfield (now known as The Field), describing its 'brooding sensation, as of the year's yawning decline rather than of a harvest thanksgiving'. As the Keeper of Art for the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery, Hewitt was instrumental in purchasing this work for the national collection where it has remained since 1955.

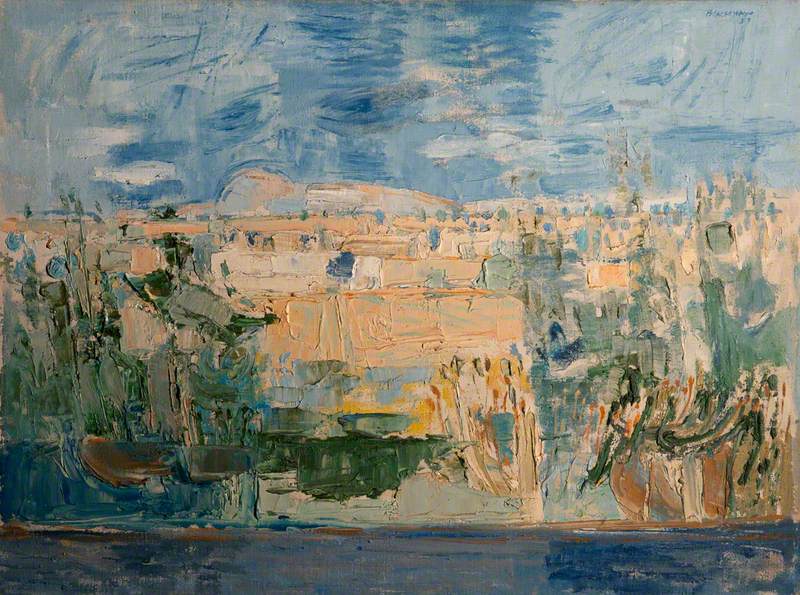

Hewitt also singled out the 'Sunday afternoon essence' of Two Men in a Field (now known as Conversation in a Field) which was also displayed in this exhibition, but not acquired by the museum until it was bequeathed in 1987. Other works from this early period, Cottage near Lisburn (1957), Culcavy Cottage (1958), Dromara Hills (1958) and Blue Landscape (1962) showed a confident and varied handling of paint and technique, with areas of thick impasto balanced with bare canvas, sketched lines and watery drips of paint.

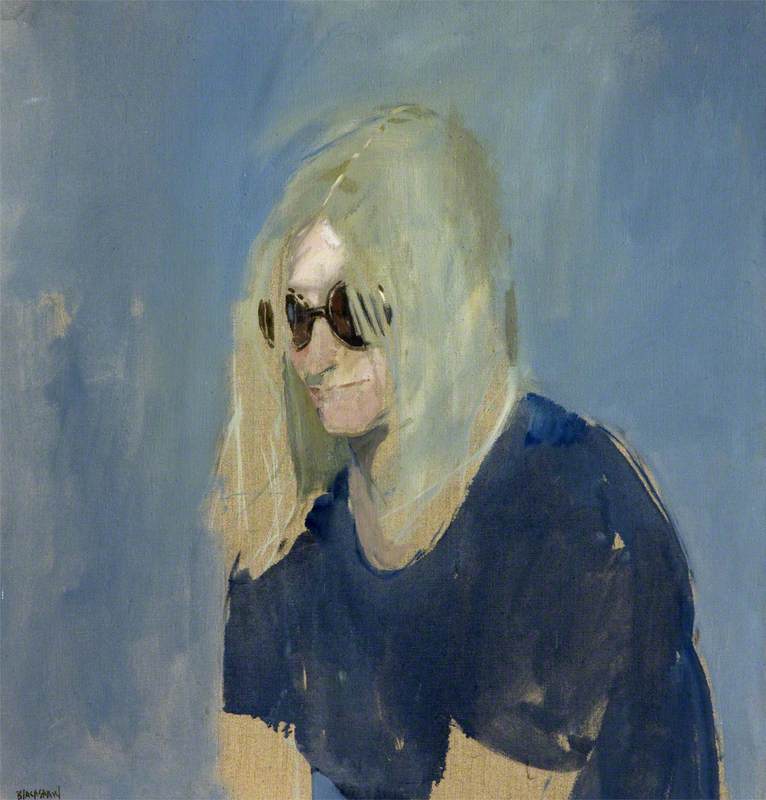

Blackshaw was commissioned to carry out many portraits over his lifetime. In Irish Arts Review, he remarked that he only liked a few of them as paintings in their own right. As well as John Hewitt who was the subject of two portraits which are now in the Ulster Museum's collection, painted almost 30 years apart, his subjects included fellow artists Cherith McKinstry, T. P. Flanagan, playwright Brian Friel, poet Michael Longley and Irish President Mary Robinson. Commissioned portraits of professors and even Lord Wakehurst, former Governor of Northern Ireland, are found in public collections. Each subject is conveyed with dignity, character and intelligence – sometimes their gaze is evasive and at other times confidently engaging with the viewer. In a review of Brian Ferren's Basil Blackshaw – Painter, novelist Jennifer Johnston marvelled at Blackshaw's ability to reveal her own hidden traits through his painting:

'When I saw the finished paintings I was struck by the fact that he had discovered in me a secrecy, a carefulness that I had never thought to be visible to the naked eye of other people…I realised that that is what painting portraits should be about, discovery and revelation.'

Blackshaw exhibited extensively in his early career including in Bristol, Washington DC, and Dublin and for a period taught part-time at the Belfast College of Art. But despite career success, Blackshaw's artistic ambition remained unfulfilled:

'About 81 or 82 I looked at the work and thought if that's what going to go on, like the racehorses exercising and so on, then I'm going to pack up painting because there's no point. I know what I'm going to paint, I know how to paint it and I know what it's going to look like when it's done. There's no exploration, no chance taken. There's no excitement in the fact of finding out something more than what you're going to do.'

He was just beginning to undo the lessons of his academic training when a devastating studio fire destroyed his works in progress, his 'diary' of drawings made in Ardglass years ago and all his materials and easels. Coupled with personal difficulties, this was a time of artistic turbulence for the artist, but also one he came to see as a huge opportunity. As Blackshaw explained to the Irish Examiner in 2005: 'I was left with nothing, but in a way, it was the best time for that to happen. There was a sort of cutting off from everything I had done before…I started off again from scratch.'

The rest of his long career was spent chasing and often capturing the elusive work 'that symbolises or gives a feeling that there's much more to the painting than the subject is.'

Paintings such as The Barn (Blue II) (1991–1992) represent a tonal shift from the landscapes that came before the fire, as well as a conceptual move away from the familiar subjects of his early career, based on the memory of a glance from a car towards a structure in the landscape and painted a year or so later. The sea of strong colour filling the canvas, defined by a light scratching of lines into the surface to relay the building's presence, as well as the 'in-motion' streak of colour above, gives the painting a spontaneous feeling, described by the artist in Irish Arts Review as 'exuberance of gesture and juicy paint'.

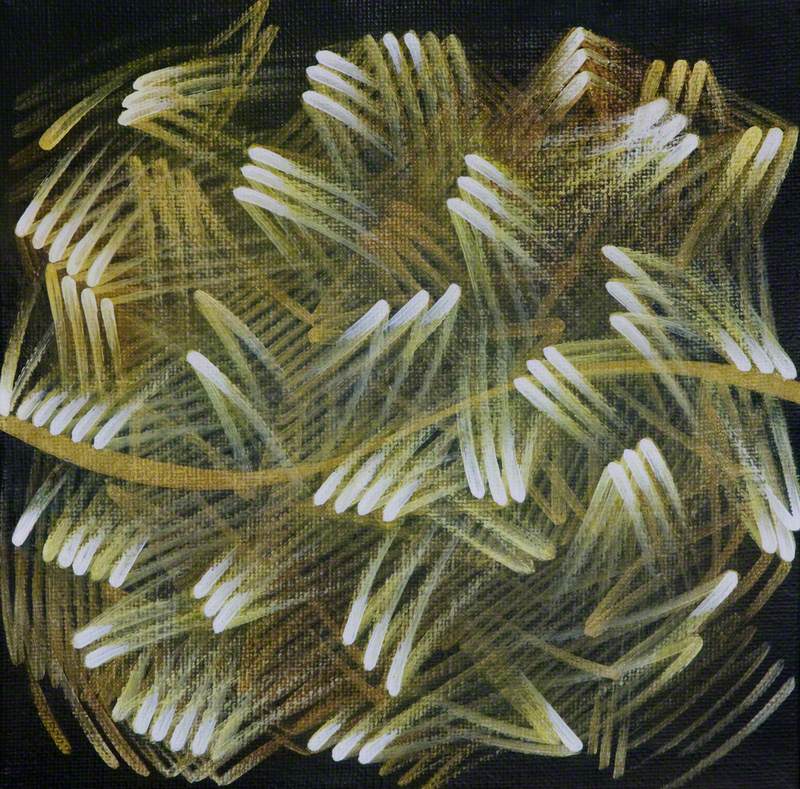

The Patient's Flower (2003) was inspired by a visit to a local psychiatric treatment centre, where the artist had viewed a display of the patients' artwork: something in their simplicity and earnestness touched him. The form, subject and technique were equally important to the artist: 'I had to paint it with acrylic washes rather than solid paint so every aspect of the art of painting comes in through the paint itself, the subject itself, the scale which is very important. All of it adds hopefully to that feeling you want to give that there's something beyond this. 'The bars at the top of the painting and the treatment of the edges all added to the sensation of enclosure the artist felt from his personal encounter.

His output, at least publicly, slowed down in the last years of his life, as he became more selective about what he painted and why:

'I do so much thinking about the subject before a painting, that's why I've only painted three or four paintings since [last year], because I'm not getting anything that gives me that rightness.' Like an ambitious and gravity-defying sculpture which relies on deep-rooted foundations, Blackshaw's later work was drawn from his vast reserves of experience, knowledge and ambition.

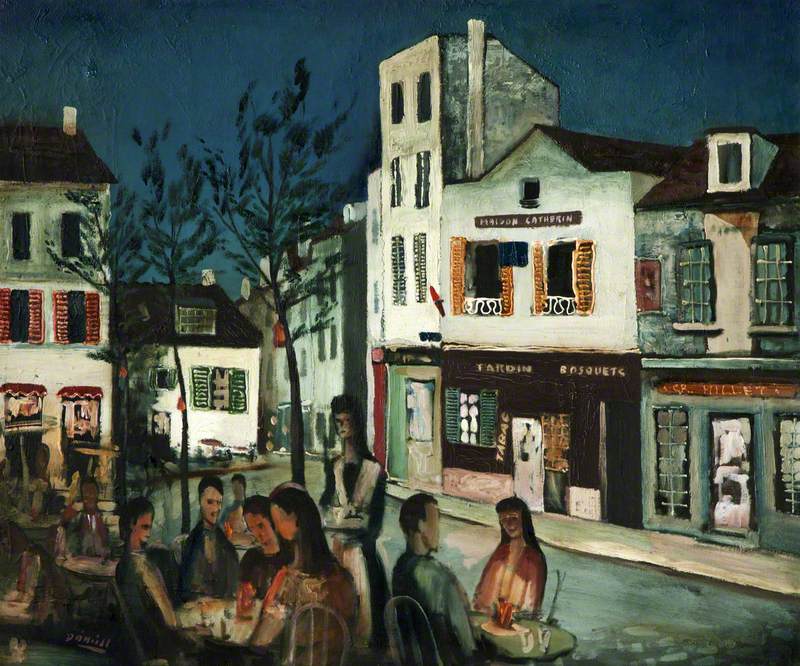

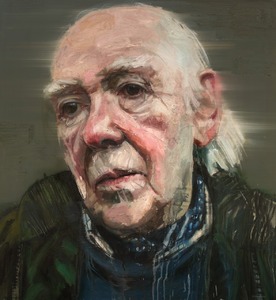

Basil Blackshaw (1932–2016)

2012

Colin Davidson

Finally, this portrait of Basil Blackshaw by Colin Davidson (who referred to Blackshaw as 'my hero' after his death in 2016) adds to our understanding of the artist, once the master and now the subject of an intimate portrait. Dressed for country living, the contours of his face are rendered in thick impasto, lending a sculptural quality to his features. He appears lost in thought, his lips slightly pursed as though on the cusp of saying something, while his eyes have a somewhat melancholy and guarded look about them. Here is an artist who was always thinking.

Claire Dalton, art historian

Unless noted otherwise, quotes from Basil Blackshaw were recorded as part of a conversation between the author and the artist in 2007

This article was supported by the Esme Mitchell Trust