Bedlam: a word that has become synonymous with disruption, chaos and, of course, madness. It's sometimes used to describe the manic nature of Christmas and there's an etymological link here, for Bedlam – the infamous hospital for the insane – is a corruption of the original Priory of St Mary of Bethlehem.

A new exhibition at the Wellcome Collection 'Bedlam: the Asylum and Beyond' (15th September 2016 – 17th January 2017) documents the history of the Bethlem hospital through historical records, works of art and film.

Many exhibits come from the Museum of the Mind, part of the modern day Bethlem Royal Hospital complex in Beckenham, South London. They include works by the ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky and perhaps the most famous of all Bethlem's artist-patients, Richard Dadd. The exhibition features a famous photo of Dadd painting at the hospital where he was incarcerated after killing his father.

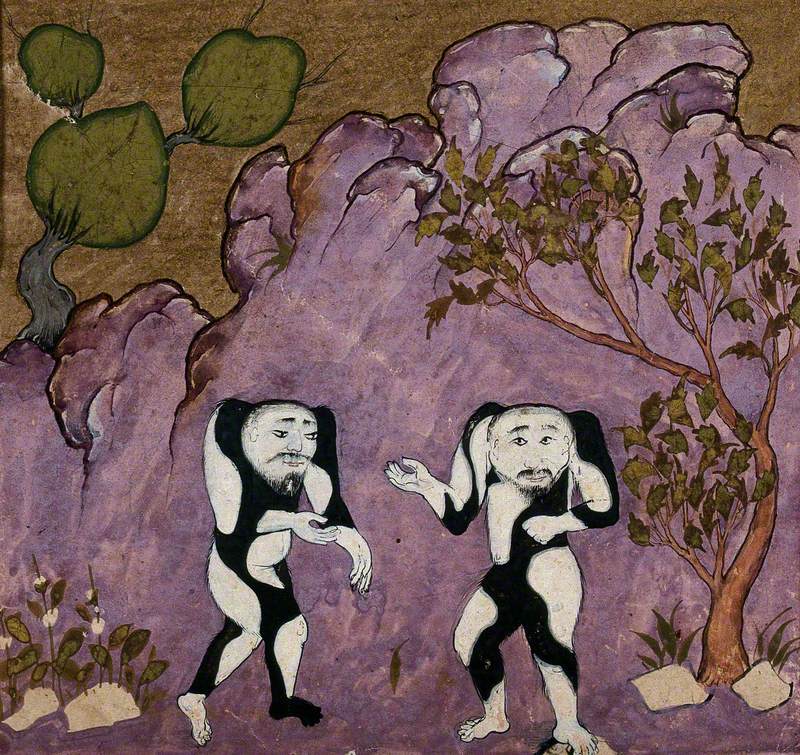

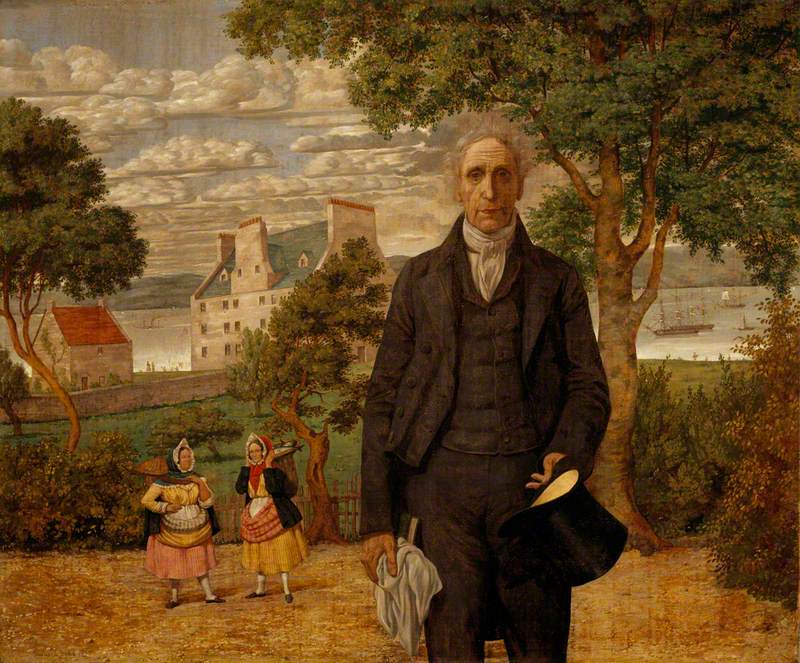

Dadd's paintings are now so valuable that the Museum of the Mind holds only one. One of his works in the exhibition is now in the collection of the National Galleries of Scotland. It is a portrait of Alexander Morison, governor of Bethlem, an 'alienist' (today known as a psychiatrist or doctor of mental illness) and a collector and admirer of Dadd's work.

Sir Alexander Morison (1779–1866), Alienist

1852

Richard Dadd (1817–1886)

Famous though Nijinsky was as a dancer, his Mask artwork reminds one of those Spirograph toys with which, like Nijinsky, you can churn out endless images based on the circle. A third notorious patient was James Hadfield, who in 1800 attempted to assassinate George III. He was lucky enough to be committed to Bethlem rather than the gallows being the first person to be found not guilty by reason of insanity. Hadfield, incarcerated for life, made many illustrations of his poem about his pet squirrel and sold works to visitors.

The first Bedlam hospital was founded in 1247 following a pilgrimage to the Holy Land as a charity for the 'lunaticke'. In 1676, bursting at the seams and under an enlightened Parliament, a monumental Baroque building was hastily constructed in Moorfields but it rapidly began to decay due to the expense of management and ever greater numbers of patients. To raise funds, the governors opened the hospital to public visits and it became part of a London tourist circuit that included the Tower, the Palaces and the zoo. The peak periods for visits were Christmas and Easter and the visitors were often drunk and disorderly.

It is from this time that the horror stories associated with the word Bedlam date. As late as 1725 the diarist César de Saussure took a London tour and described the long galleries bordered by cells where 'inoffensive madmen' walked about. A print of William Hogarth’s The Rake in Bedlam – illustrates not only these inoffensive madmen but the often offensive ladies who came to mock them: 'On holidays numerous persons of both sexes... visit this hospital and amuse themselves watching these unfortunate wretches, who often give them cause for laughter,' wrote de Saussure.

Notwithstanding the fund raisers, by the 1790s Bethlem’s palatial structure was beyond repair while a parliamentary investigation had revealed that the underfunded and understaffed hospital regime had sunk into cruelty and neglect: an all too familiar story. Among the scandals revealed was that of the inmate James Norris, whose image (on loan from the Museum of the Mind) shows him chained to the wall by the neck. Funds for a new hospital were granted and in 1810 a public competition to design a new hospital building was held.

Bedlam In London: Wellcome exhibition explores infamous institution https://t.co/RbmcBzXudq pic.twitter.com/2PkzyL2JtP

— Londonist (@Londonist) January 14, 2017

Among the most poignant items in the Wellcome exhibition are the drawing and notes submitted by James Tilly Matthews, confined in the old building as an incurable lunatic, which are the first plans for a mental hospital designed by a patient. Matthews' thoughtful 28 page exposition was met with a one line letter: 'The plans however ingenious are not fit to be laid before the College of Physicians and are irrelevant.'

The new Bethlem – that of today – was eventually built in South London. Its one decorative feature – a dome resembling appropriately a birdcage – features on the cover of an in-house magazine, Under the Dome, produced by patients. By the twentieth century, the use of therapies including art and writing formed part of more enlightened treatments for psychosis. Bethlem today has studio facilities for art, woodworking and textiles, and an on-site gallery where work is presented to the public. Sadly, many mental health issues remain a challenge today.

Andrea Marechal-Watson, International Editor, International Property & Travel magazine

'Bedlam: The Asylum and Beyond' was at Wellcome Collection, London from 15th September 2016 to 17th January 2017.