In 1963, exactly 60 years ago, Coco Chanel chose a fabric for her couture collection from a relatively unknown designer of textiles based in the Scottish borders. The fabric was a brilliantly coloured mohair tweed and the designer was Bernat Klein (1922–2014), now the subject of a retrospective at National Museums Scotland.

Mohair tweed inspired by a painting of a rose and selected by Chanel

1962, fabric by Bernat Klein (1922–2014)

Chanel was not alone in falling for Klein's revolutionary new cloth – in their spring collections that year, London couturiers John Cavanagh, Jo Mattli and Victor Stiebel also used the fabric, described by Ernestine Carter, fashion doyenne of The Sunday Times as a 'completely new fabric: soft, woven into broken checks or stained-glass patterns in off-beat colours.'

Loch Lomond

1961, fabric by Bernat Klein (1922–2014)

That summer, at a preview of his autumn fabric collection, Klein exhibited some of his own paintings alongside the textiles, revealing the synergetic connection between the two. Just as the Scottish Colourists broke new ground in painting, here was a designer, and sometime painter, using a forensic approach to colour to revolutionise the world of textiles, and in particular Scottish tweed.

Six woven womenswear fabric samples

c.1965, mohair tweed by Bernat Klein (1922–2014)

Klein was born into an Orthodox Jewish family in Senta in the former Yugoslavia (now Serbia) and escaped the Holocaust in which many members of his family perished. This was thanks to his being sent away to study in a religious school in Jerusalem. At the age of 17, he rejected this form of education and entered the Bezalel School of Art and Craft in Jerusalem which opened his eyes to the world of art for the first time. There he also had his first taste of textile weaving.

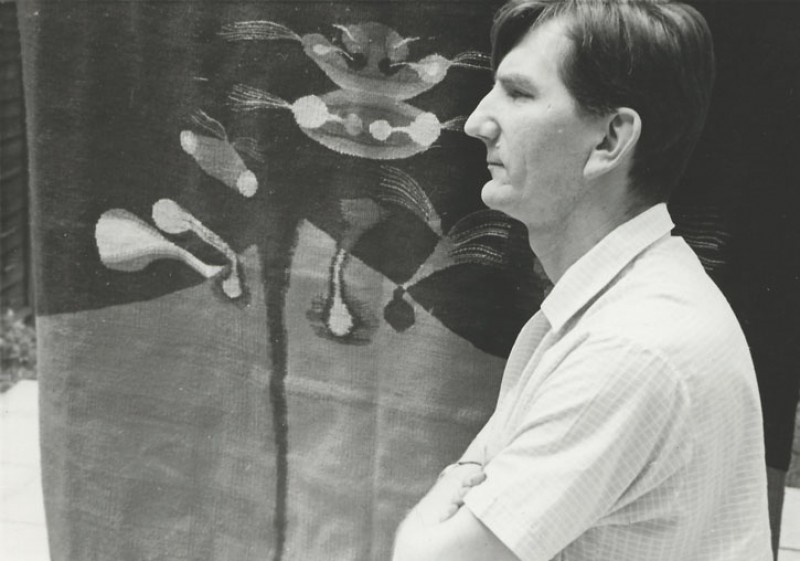

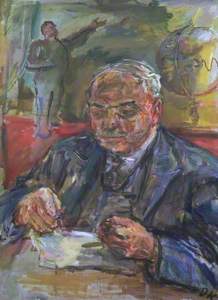

Bernat Klein selecting cloth and yarn samples

Klein's parents had been involved in both the wholesale and retail aspects of the textile industry so when he was young he had had the opportunity to observe the industry at close quarters. This, and the realisation that he would benefit from learning English, prompted him to study textile design at the University of Leeds. As he remarked to a fellow student on the ship over to England 'I just like playing with colours'.

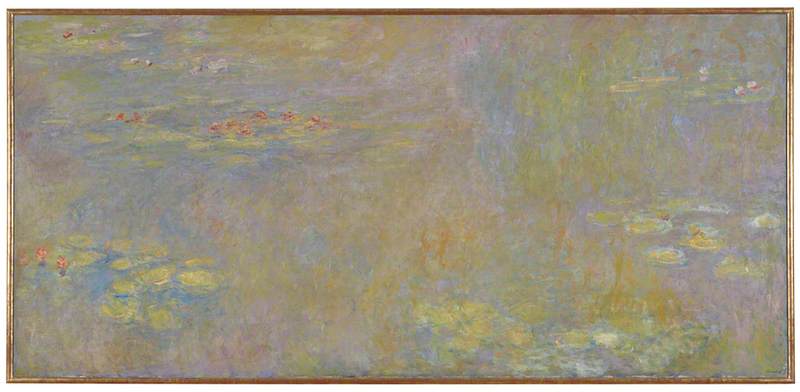

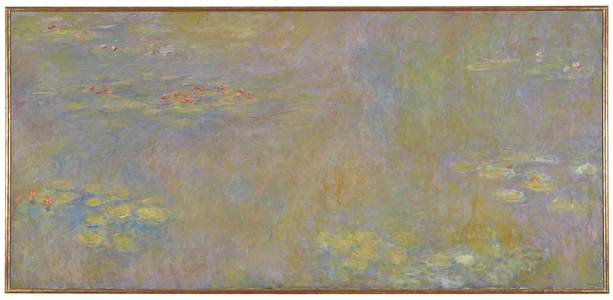

Klein was to remain passionate about colour for the rest of his life, illuminating both his textiles and paintings with vibrant hues frequently inspired by nature. He embraced the work of painters whom he felt broke new ground in their use of colour, such as Monet, and developed his own highly technical theories about colour in woven and printed fabrics, as well as in personal style.

Klein admired artists who, he felt, had liberated colour so that it could be used freely. Turner was one example. Klein saw in his work a technique that used colour not just as a tool but as something endowed with new powers of expression, bringing it to the forefront of a work. He felt Turner was, in the words of Paul Klee (whom Klein also admired) making 'the invisible visible' and this was what Klein aimed to achieve in his textiles.

Interior of a Great House: The Drawing Room, East Cowes Castle

c.1830

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

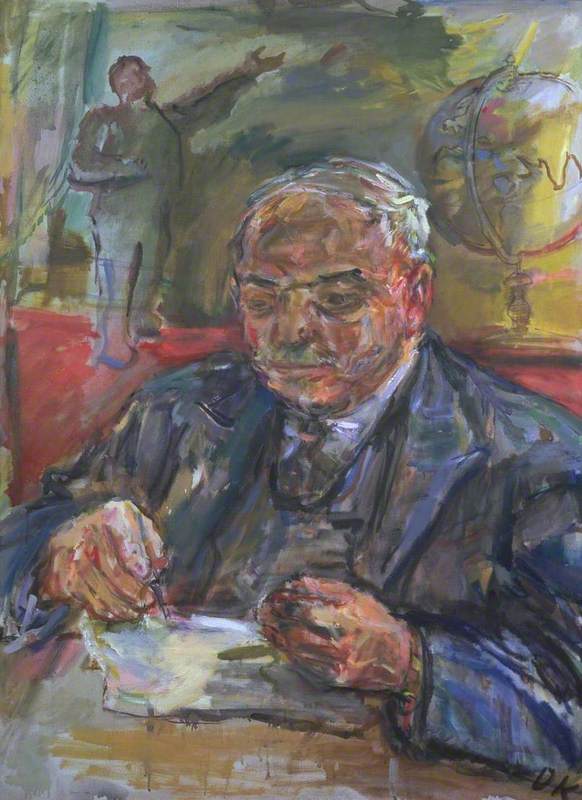

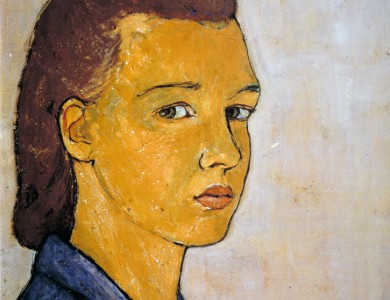

He found Oskar Kokoschka's rendering of colour thrilling, remarking of one portrait that 'instead of delicate flesh tones there were raw splodges of seemingly thrown-on paint in assertive colours'.

In 1952, after a few years of working for textile companies in England and Scotland, Klein set up his own company in Galashiels in the Scottish borders, producing rugs and furnishing fabrics. Though initially unsuccessful, he broke through into major markets with an order of lambswool scarves for Littlewoods, and soon he was supplying many top high-street retailers. He then switched his business to manufacturing woven fabrics for men's and women's suiting.

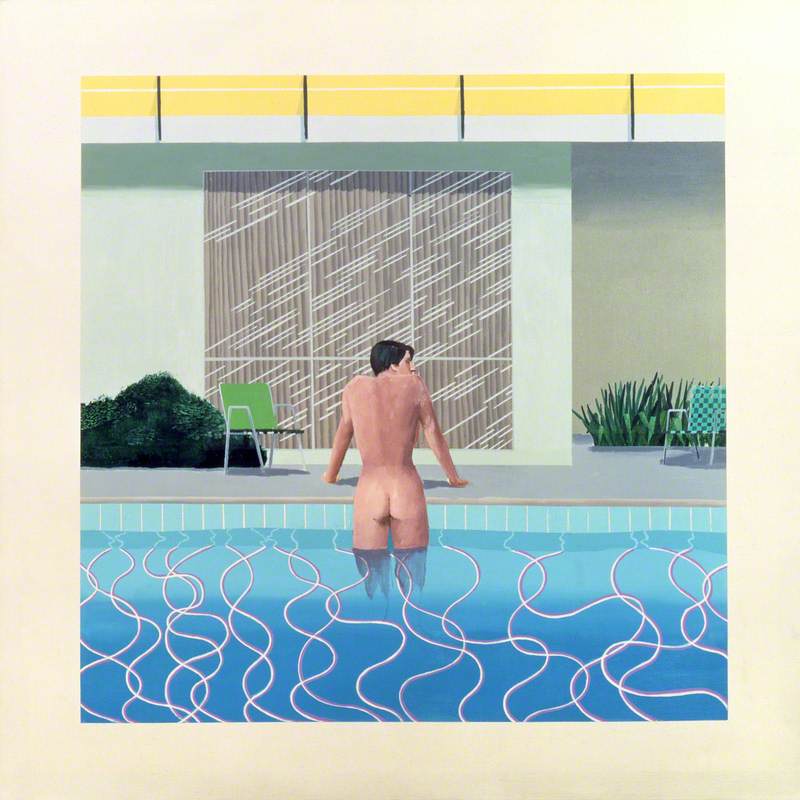

A couple of years later, at Tate, Klein saw the painting that was to affect him most profoundly and influence his entire approach to colour and textile design. It was Georges Seurat's Bathers at Asnières.

In this work, Seurat appeared to exemplify Klein's theory that 'Colour perception…is a matter of interaction with neighbouring colours.' By this, he meant that by surrounding a colour with a halo of its complementary colours, the effect would be to achieve a luminescent hue far superior to a single flat colour. Through his pointillist technique, comprising a multitude of small fingernail-sized dots of colour, Seurat gave Klein the idea to experiment with yarn, dye techniques and weaving innovations that were to shake up the tweed industry like never before.

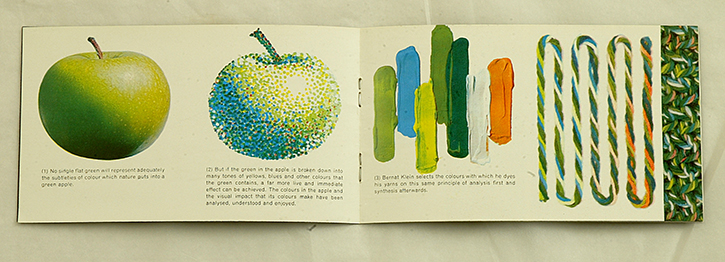

'A New Movement in Colour'

leaflet to accompany a garment, demonstrating nature as a source of inspiration for Klein

Just as Seurat's dots of colour required the viewer to stand back and allow the eye to mix them to realise the grass, water and sky of the scene, so Klein set about achieving the same in his weaving. As he said to his wife Peggy, herself a talented knitwear designer, as they left Tate that day: 'I wish I could weave cloth which looked like that.' Later he was to explain how he 'dreamt of cloths that contained not just three or four colours as is usual in textiles, but dozens and dozens of them.'

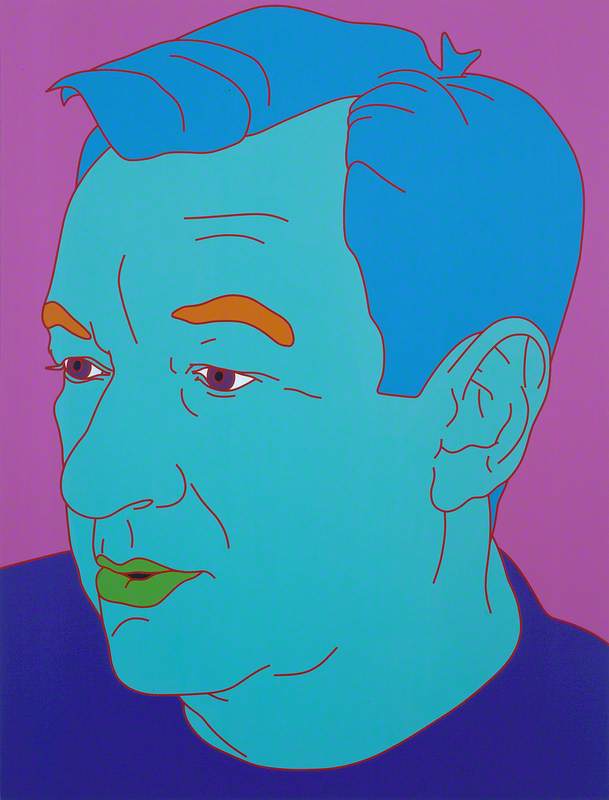

Tulip

1962, oil painting by Bernat Klein (1922–2014)

Klein took up painting himself in 1960 and one of his most significant early oils, Tulip, was used repeatedly in his publicity, demonstrating the close relationship between his art and his textiles. It was the inspiration for a rug created in 1967 for a company named Tomkinsons. Areas of the rug that appear to be of flat colour are actually made up of many individually coloured yarns, in line with Klein's theory of colour.

Tulip Petals

late 1960s–early 1970s, rug designed by Bernat Klein (1922–2014) & manufactured by Fiedler Fabric

Klein realised that merging areas of balanced colours together was more effective than using tones of the same colour. He created a dictionary of 5,000 balancing colours in order to speed up the designing of his textiles.

After a long period of experimentation and disheartening failures, in the early 1960s he finally managed to develop a technique of space-dyeing yarns in five or six colours for suiting fabrics. This involves dipping sections of the yarn in different dyes along the piece and, though appearing to be random, is a tightly controlled process.

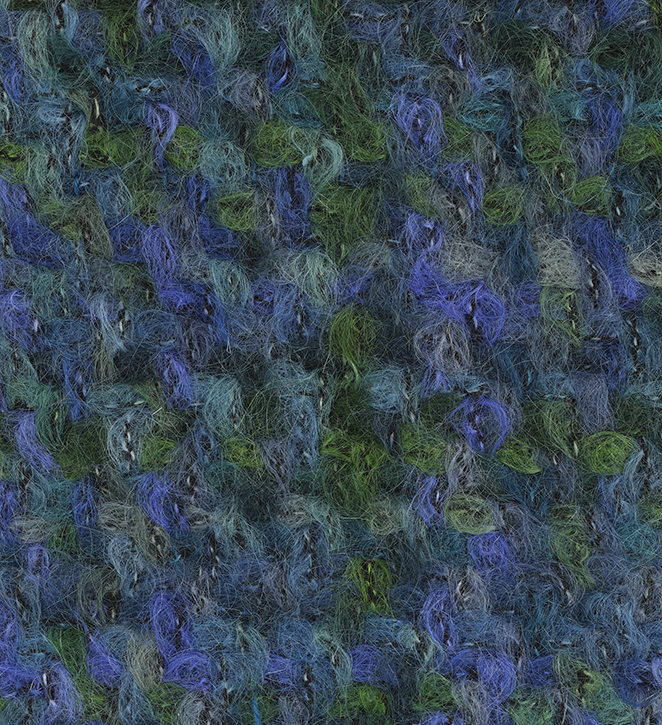

Marmara

1967, fabric by Bernat Klein (1922–2014)

Klein combined mohair, which was bulky but also light and silky, with wool and worsted yarns and occasional fancy looped and bouclé yarns. The resulting luxury fabrics were heralded by the USA's Wool magazine in 1962–1963 as a breakthrough and Klein himself as 'an unusual combination of technician and artist.'

Tweed using slubby and multiply yarns in pink, green, yellow and orange

1960s, fabric by Bernat Klein (1922–2014). A good example of colour balance

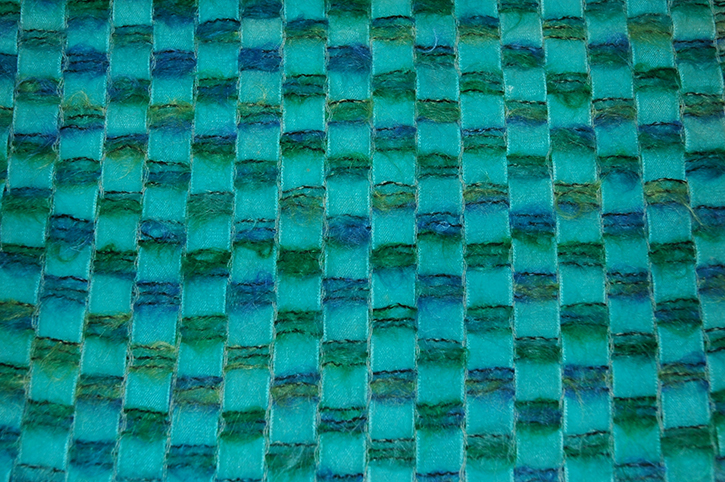

In 1964 Klein caused a fresh sensation with the introduction of his technically complex velvet tweed which combined velvet ribbon with brushed space-dyed mohair into a fabric. The tweed had couture houses clamouring for their own versions. Celebrities and royalty, including Princess Margaret, wore the fabric in suits, coats and even evening dresses.

Velvet tweed comprising turquoise ribbon with green, blue and yellow space-dyed mohair

1960s, fabric by Bernat Klein (1922–2014)

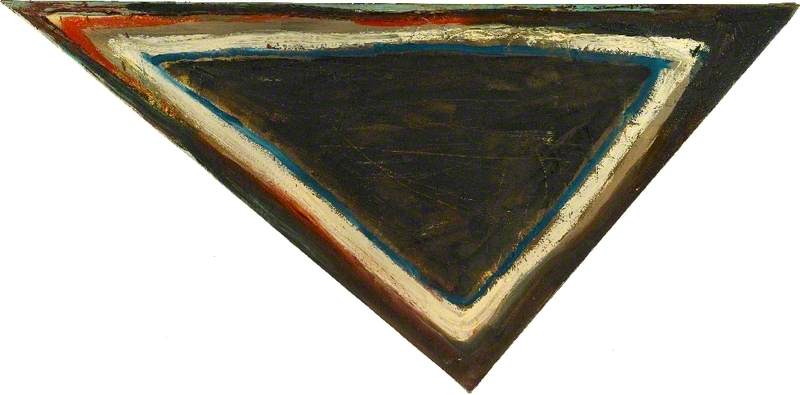

One particular blue colourway was influenced by his painting Seascape which drew its inspiration from an aerial view of the sea outside Rome.

Seascape

1963, oil on board by Bernat Klein (1922–2014)

Dress in velvet tweed next to 'Seascape' in the 'Bernat Klein: Design in Colour' exhibition

Wool magazine likened Klein's fabrics to pointillist paintings, enthusing that 'it is rarely that so many bright mixed shades have blended together so serenely, except perhaps in nature.'

Nature was indeed deeply embedded in Klein's painting and design. High Sunderland, the modernist house he commissioned from architect Peter Womersley in 1957, was designed expressly to bring the outside world in and give its inhabitants a front-seat view of the changing seasons in all their glory.

High Sunderland, in the Scottish Borders

designed in 1957 by Peter Womersley for Bernat and Margaret Klein

Klein drew on the beautiful environs of his home for inspiration for his paintings. From the outset, he applied the paint with a palette rather than a brush, seeking to break down the colours he observed in nature in order to identify the colour components. It's easy to see how the ideas flowed smoothly into his kaleidoscopic tweed designs.

Autumn Trees

painting by Bernat Klein (1922–2014)

He attempted to capture the pinks, reds and greens he observed being generated by sunlight flashing through the leaves of a copper beech tree, and the many tones of some frozen lichen he came across while walking in his grounds. He relished 'the intellectual exercise involved in translating an object from nature into a colour study.'

Maple

1961, fabric by Bernat Klein (1922–2014)

In the early 1960s, Klein experimented primarily with reds and oranges in his painting, moving later to blues inspired by the sea and sky of the Côte d'Azur. Occasionally he represented close friends and family in particular colours, such as blue-greys, and turquoises for his beloved wife Peggy. In the year following her death, he refused to paint with any colour other than blue.

Although Klein is known as a brilliant and visionary textile designer and colourist rather than a painter, his extraordinary output of paintings played a key role in allowing him to experiment with colour, capturing the light and shade of the natural world and allowing it to play out in his glorious fabrics.

Lucy Ellis, freelance writer and editor

'Bernat Klein: Design in Colour' continues at National Museums Scotland until 23rd April 2023

Further reading

Bernat Klein and Lesley Jackson, Bernat Klein: Textile Designer, Artist, Colourist, Bernat Klein Trust, 2005

Bernat Klein, Eye for Colour, Bernat Klein / Collins, 1965

Shelley Klein, The See-Through House, Vintage, 2021