Art has always served as a powerful medium for socio-political commentary. Artists have found imaginative and powerful ways to use their craft as a vehicle for critical analysis of the environment around them. Yet, more often than not, their message isn’t heeded. Time passes and nothing changes.

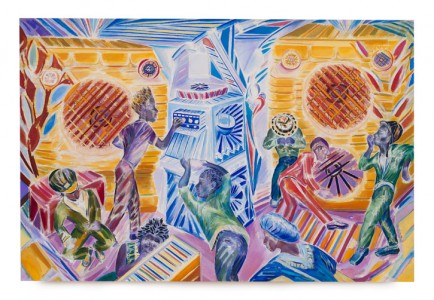

Look at the political climate today and you find that it bears a striking familiarity with the landscapes previously crafted by artists in the past. A case in point, Nigeria today bears an eerie similarity to the landscape envisioned by Tam Joseph in his painting Monkey dey Chop, Baboon dey Cry. It borrows its title from the pidgin phrase ‘monkey dey work, baboon dey chop’, which refers to the exploitation of people by those in power. Joseph’s painting is a strong critique of corruption, abuse of power, inequality and exploitation. He paints a landscape of an unknown African country and fills it with distorted figures: a military official, a woman mowing the land with a baby on her back, a skeletal figure, a white man aggressively reaching unto a woman’s face in a car and another white man taking notes on the scene.

Joseph’s painting highlights the abuse of power between the government and the people. The people work hard to provide for their loved ones and some suffer in poverty as the wealth of the nation fails to better their lives. Even those who can afford the luxuries such as a Mercedes Benz aren’t fully insulated from the abuse. Save from the elites, the rest of the people find themselves exploited and abused.

Looking at the Nigeria of today, it can be argued that the situation on the ground is more or less the same – if not worse – as the painting. A country where politicians pass as around power like it’s their birthright, stuck in a perpetual cycle of rinse and repeat.

Growing up in Nigeria, my house was always charged with intense political discussions. Visiting family members would engage my father on the political situation and what solutions could be sought in the never-ending fight against political corruption. My father would argue fervently that what we needed was a change in government, a strong group of leaders that could stand against corruption and lead us into better times. This was largely the wave that carried Muhammadu Buhari to the presidency in 2015.

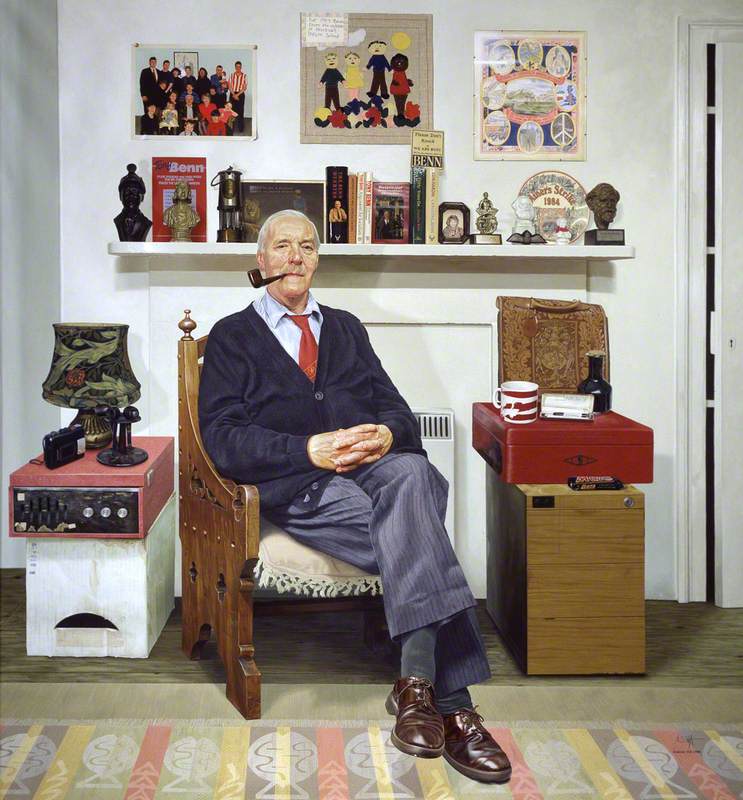

There exists a divide between people and politicians. A feeling that governments fail to understand the plight of the people they are supposed to represent, rather catering to the elites.

This memory played on my mind as I listened to my father tell me – with a defeated voice – that he hadn’t bothered getting his personal voter card for the upcoming elections. To him, the vote didn’t matter, 'at a state [Lagos] level we all know who will win, on a national level, all the faith that filled the previous election has only resulted in a worsened economy and more corruption'. His faith and energy had been expended in 2015, so why bother going through it again?

Now, living in London, I find myself viewing the situation in Nigeria as an outsider looking in. In some ways similar to the white figure observing the scene in Joseph’s painting. Yet, over on this side of the world, the ineptitude that we are told only fills non-Western politics seems to have caught on. Between the Brexit crisis and Donald Trump, it has become hard to tell the difference between governments we expect to be corrupt and dysfunctional, and those upheld as examples to strive towards.

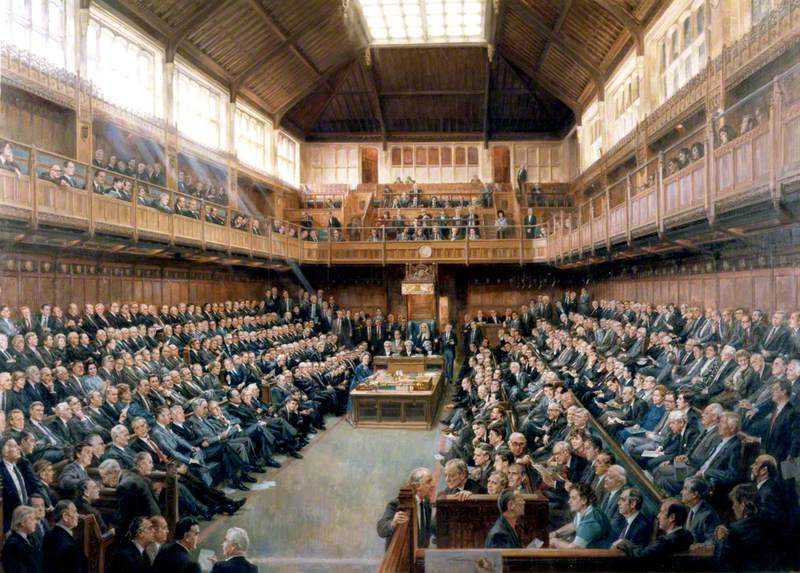

The political chaos engulfing the UK, USA and Nigeria echo Robert William Buss’ The Mock Mayor painting. Buss, satirising the daily life of early Victorian times, depicts the election of a mock mayor. Feeling disenchanted with politicians and the elite, townsfolk would elect a mock mayor in jest of their leaders. Buss’ painting is filled with chaotic energy, simultaneously capturing the tradition in all its absurdity – with the mock mayor at the centre – and highlighting its nature as a protest to those in power, looking on in dismay in their top hats.

Buss powerfully uses satire to depict the breakdown in the relation between the people and the government. The irony is we find ourselves in a time where real-time politics is more absurd than what satirists can come up with. After all, what’s a mock mayor to a mock parliament and a mock president? Or in the case of Nigeria, a potentially cloned president?

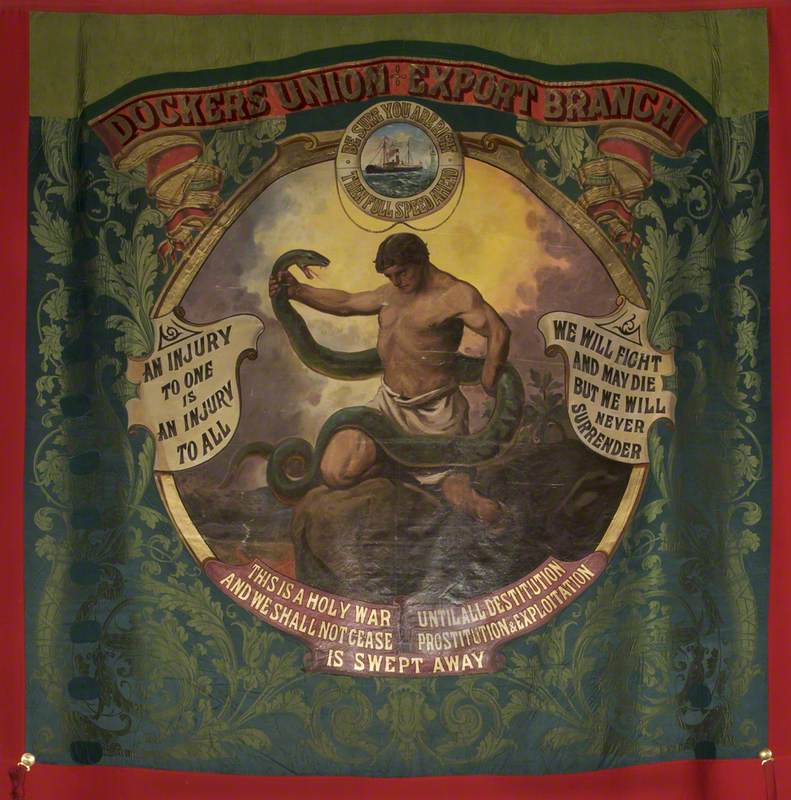

The tradition of the mock mayor offers a view of a past moment in time similar to the present. There exists a divide between people and politicians. A feeling that governments fail to understand the plight of the people they are supposed to represent, rather catering to the elites. This has led to increased political apathy and sparked extreme reactions from the people. As a case in point, Britain’s EU Referendum and Donald Trump’s rise to power, were all, to a certain extent, people’s reaction to a political system they feel continues to exploit them and take them for granted. It all plays into the warnings sung by Nigerian musician Fela Kuti in his song Unnecessary Begging: ‘Monkey dey work, baboon dey chop / Baboon dey hold dem key of store / Monkey dey cry, baboon dey laugh / The day monkey eye come open now...’

The people’s eyes have opened, and they do not like what they see. If artists can see that, why can’t governments?

Damilola Ayo-Vaughan, writer, photographer and filmmaker