The title of this story, 'Beyond Tomorrow', is taken from a sculpture designed by Karin Jonzen (1914–1998) and encapsulates, for me, the rich resource resulting from the Art UK Sculpture Project, for which I worked as a Volunteer Data Researcher.

My passion for art led me to volunteer for Art UK. This started back in 2009 and I have contributed my time in various capacities in the organisation as it expanded, changed its name, and widened its focus. In 2017, I was invited to join the Art UK Sculpture volunteer network. I chose to be a Volunteer Data Researcher, as it matched my professional skills.

Mae Keary

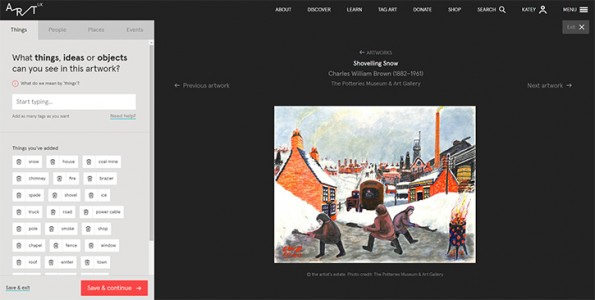

The research area assigned to me was the City of London. I was presented with an Excel spreadsheet listing over 9,000 sculptures, compiled by the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association, a partner in the Art UK project. My task was to process each of these records and complete the fields by researching for missing data.

Work on the documents started in late 2018, and at first my knowledge of sculpture was rather basic – an appreciation rather than in-depth knowledge – so I realised it was going to be a learning experience. The early files were rather daunting, working from data sheets, some with faded pictorial evidence of old sculpture sites and piles of rubble remaining, and for others, nothing at all. I had to dig deep to carry on, but I was determined to find out where the real sculptures existed.

Chartered Accountants Hall

1890 & 1970

Harry Bates, Hamo Thornycroft, James Alexander Stevenson, David McFall

After completing my first 300 records, I recognised a change, as what I considered to be real sculptures began to appear, and the database that I was completing began to make sense. The features I had to describe were decorative rather than commemorative, such as facades of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century buildings with reliefs – caduceus keystones, crowned monograms and cartouches above doorways, royal arms, heralds, etc. I became quite familiar with the terminology.

Sir John Cass (1661–1718)

1998

Louis François Roubiliac

I researched eighteenth- to twentieth-century statues of royalty and other prominent figures, decorative ceramic plaques, spandrels and scrolled pediments, panels with lengthy faded inscriptions, lanterns, pumps, fountains, gateways and friezes. Allegorical figures depicting progress, commerce, justice and learning, were researched, as well as dragons and gryphons. They all enhanced my learning curve in the terminology of architecture and sculpture.

There were the famous buildings of London to research – St Paul's Cathedral and its churchyard, the National Postal Museum, Livery Buildings, banks, churches, war memorials, public squares and pubs. I discovered parts of London I did not know! In fact, the classification of sculpture as an art form appeared to be very far-reaching.

Swan Marker and Barge Master

2007

Vivien Mallock

A special highlight was to discover the prominent sculptors and architects of the day, such as John Soane (1753–1837), Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811–1878), Charles Holden (1875–1960), Jacob Epstein (1880–1959) and Sir Charles Wheeler (1892–1974).

A Conversation with Spike (Milligan)

2014

John Somerville, Charles Holden, Leonard Holcombe Bucknell

Along the way, I discovered the many renowned international sculptors who travelled from different parts of the world to ply their skills in this country and make their mark. Finally, we must not leave out the many women who competed on equal terms with their male counterparts, such as Eleanor Coade (1733–1821), Susan Durant (1827–1873) and Elizabeth Frink (1930–1993).

Later in the project, I was privileged to conduct data research on contemporary sculptures in Leeds and Hull, adding a different dimension. At last, I was dealing with live records. Some of the sculptures were still old, but there were current three-dimensional photographs to work from, and this made it much easier to trace them. They were better documented, as there were websites of regional archives, plus other useful online sources. Finding relevant data was more pleasurable, and classifying the sculptures became more meaningful.

It has been a totally satisfying experience to be a part of this sculpture project, and to see the results of one's efforts on the Art UK website as a public resource. Also, it has been a pleasure to work with the Sculpture Project team, who were very supportive and looked after their volunteers extremely well.

Mae Keary, Art UK Volunteer Data Researcher

Art UK thanks each and every volunteer that contributed their time to capturing an incredible record of public sculpture in the UK.