This story is part of a series about the representation of multiple gender attraction in arts and heritage, using research undertaken as part of the Whose Heritage? research project at Culture&. For more information, you can read the introduction to the series, and discussion around terminology.

Gwen John, born in Wales in 1876, is known for her oil paintings of women, cats and interiors. John gained more recognition after her death and she became a prominent figure in feminist art critique. With the first major exhibition looking at queer British art only happening in 2017, it is unsurprising that there has been little discussion about John's work and her attraction to multiple genders. By highlighting this part of her identity, we can resist bisexual erasure within the art world.

Most discussions of John's life skim over her sexuality. In 1985 the Barbican held one of the largest exhibitions on the artist but the exhibition catalogue makes no mention of her attraction to women. It is not clear if the feelings she had towards women were reciprocated but it does not mean that these feelings and emotions are not important to understanding John's life and her art.

Many of the biographies written about John have been shaped by her writing. John wrote countless letters to friends and lovers that offer us another biographical perspective of her life besides her artwork. Many of her letters are at the National Library of Wales. It is through these letters that we know of Gwen John's relationships with men and women.

Biographers and researchers have explored John's fondness of spending time alone, analysing this in many ways – especially how quiet interiors are the focus of many of her artworks. She has been written about as 'chaste, subdued and sad'.

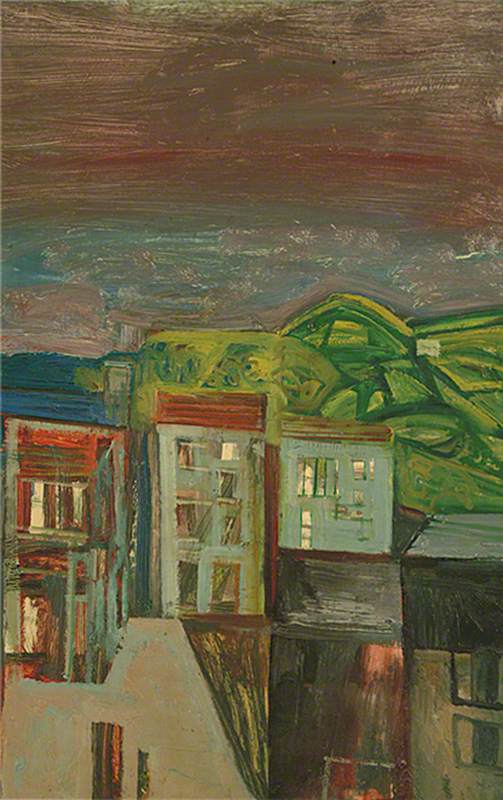

John moved to Paris in 1904 and never properly returned to London. It was around this time that the 'New Woman' emerged – women were living more independently, questioning inequality and had more sexual freedom. John, in moving to Paris and living alone, had the opportunity to explore the freedom of living in a different country, experimenting with art and meeting new people. There is much to suggest that she was not isolated but valued her independence, and through her writing we can read of her adventures in Paris modelling for artists, meeting friends, painting and walking the streets of the city. Her independence challenges the idea that a woman cannot enjoy living alone: an assumption that a woman's relationship with a man makes her life fulfilling.

Gwen John was exploring the city as a new woman, taking part in what was known as a 'bohemian' lifestyle where artists and creatives could explore unconventional ways of living. Paris in the early twentieth century was a place where women who were attracted to women were able to explore their sexuality in the range of bars, cafés and restaurants, and at the exclusive salons held by women at this time. There is no concrete evidence to suggest that John attended these places but the people she met and her association with bohemians suggests she knew of this subculture.

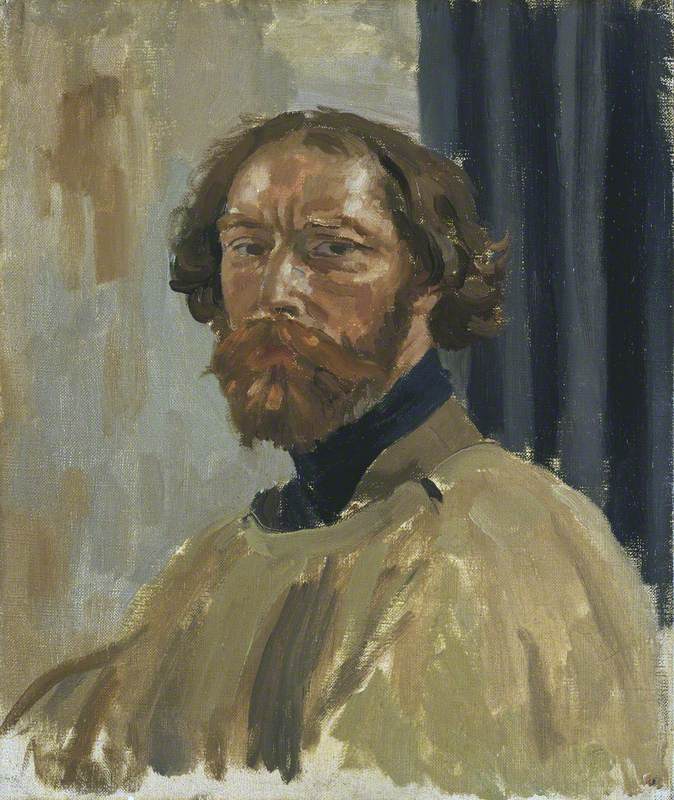

John is often described as being overshadowed by the men in her life, both during her life and after her death. Her brother Augustus John was a well-known artist who attended the Slade a few years earlier than Gwen. Augustus claims to have known that Gwen was a better artist than himself. It was in his autobiography that he writes of his sister's romantic interest in a fellow student called 'Elinor':

'One of my sister's unhappy crossings in love led to a drama. She had a great friend at the Slade, a certain girl student whom I will call Elinor. Elinor had formed a close attachment to an outsider... Gwen decided that this affair must be stopped; so, after failing to persuade her friend to break it off, she announced her ultimatum – surrender or suicide.'

Gwen John is also known as the lover of the famous French sculptor Auguste Rodin. A Lady Reading has been read as a self-portrait of John waiting for Rodin to come to her apartment, as similarities can be seen between the figure in the painting and Rodin's sculpture for which John modelled. The interior in this painting is John's room in Paris, and you can see a pen and paper on the writing desk.

The main subject of discussion regarding John's love life has been her relationship with Rodin, and whilst they were not always romantically involved they were still in contact until he died in 1917. Although we can't deny that this decade-long relationship was an important one, his fame and John's position as a female artist may have somewhat exaggerated his influence on her art and life. Rodin's death is considered the point when her life changes: she finds Catholicism and spends the rest of her days as a recluse.

However, we know from her letters that she formed strong attachments to women after this time. Susan Chitty writes in her biography of John that she had 'a passing feeling for an Englishwoman called Nona', whose identity is unknown. We also know that John became infatuated with Vera Oumançoff. These letters defy the notion of John's reclusivity, a perspective that again relies on heteronormative understandings of relationships.

Her attraction to people has been often described as intense. She was known to have written to Rodin most days, calling him 'master' and signing off her letters using the name 'Marie', possibly a term reserved for people she was romantically involved with. She is said to have followed Vera Oumançoff home from Mass every Monday, writing her frequent letters and drawing her pictures. Gwen John also asked Vera to call her 'Marie'.

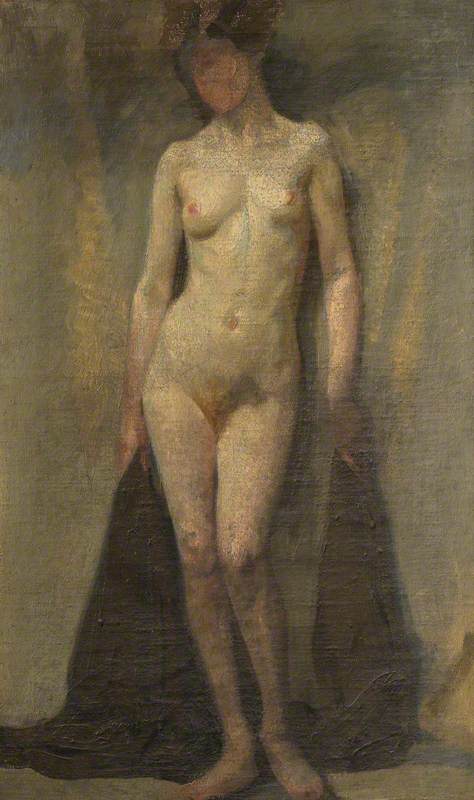

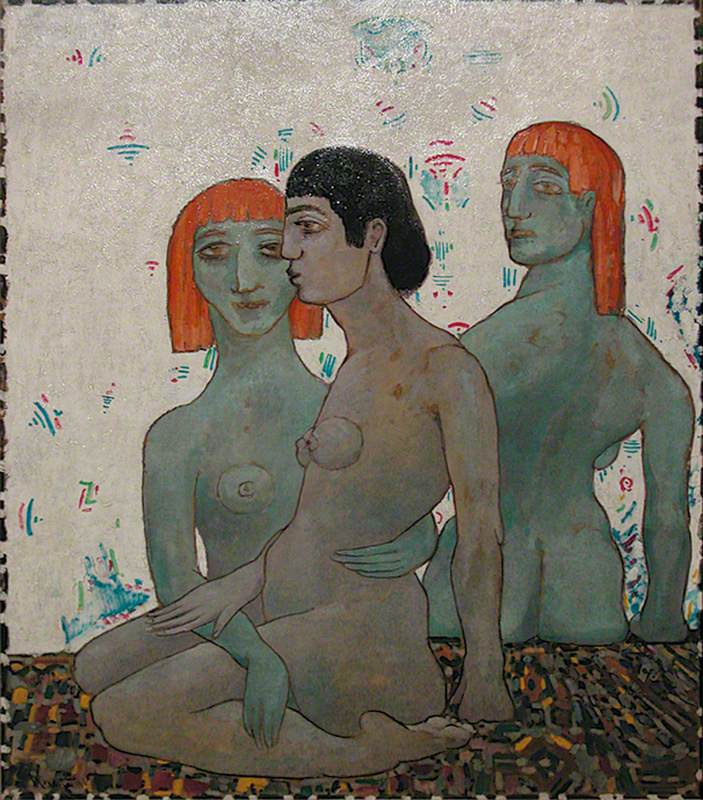

John was friends with the artist Mary Constance Lloyd. The pair met during their time at the Slade. They became lifelong friends and Lloyd owned several of John's works. Lloyd also moved to Paris and in 1905 she painted this nude of Gwen John in that year. John apparently preferred modelling for women artists. There are a few letters exchanged between the two. In one, John wrote: 'I came home from being with you this morning with my big roll of English Literature. I put it on the table and sat by it and thought of you and was not lonely. Now it is evening and I still don't want to read.'

Can we read something further into this relationship through this painting? Whether an intimate friendship or more, Lloyd's painting shows us another side to Gwen John. Compared to John's self-portraits especially, this painting is lighter and softer. John has no features on her face yet this painting feels like we are being intrusive, catching John in a private moment.

John chose to focus on painting women, rooms and cats. Some of the paintings are of her own rooms, highlighting the importance of her own personal space, with cats as her companions. John does not paint any portraits of men and chooses to focus on women. As she modelled herself during her time in Paris (which is how she met Rodin), she may have found the process of painting women easier and more interesting. The women in her paintings are not as passive as they first seem: they are often holding books and reading.

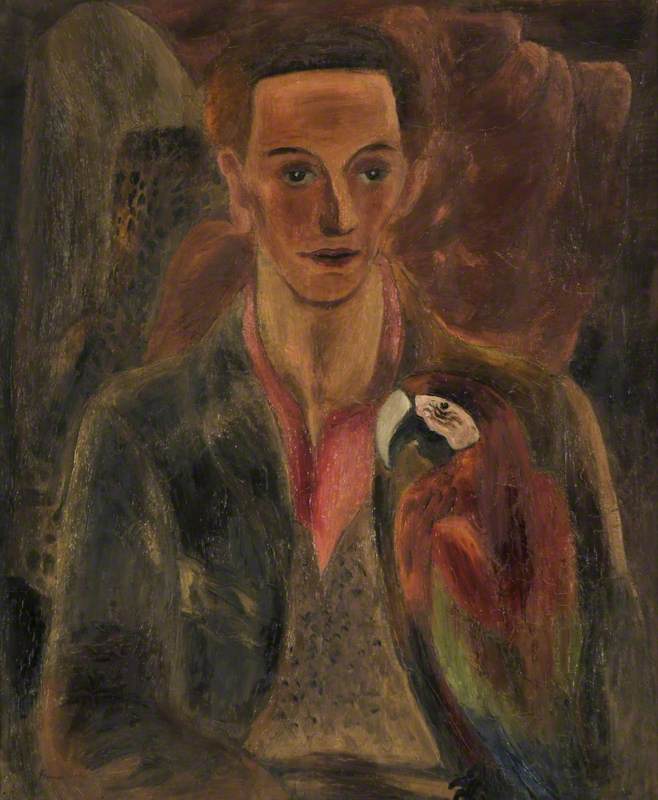

Looking at Nude Girl, there are so many layers to this piece of work. There is an intimacy in this painting between the viewer and the model, and the seated position and the model's stare both suggest confidence. John joined the Slade as one of the first female art students to be able to participate in life-drawing classes. It is a painting of a woman by a woman, therefore we are not viewing the model through the male gaze. Many believe John disliked Fenella Lovell, who modelled for this painting. She said: 'It is a great strain doing Fenella. It is a pretty little face but she is dreadful.' This portrait offers a perspective on the feminist ideal of the 'New Woman' and John's attraction to women. There is a depth to this painting beyond eroticism: it can be read as sexualised, but it is not the only way to see the subject.

John used the same models again and again. We have Ellen Theodosia Boughton-Leigh, known as Chloë, who appears in various paintings by John.

She also painted Dorelia McNeil, a friend she studied at the Slade with, and who also walked with her from London to Rome in 1903. Gwen introduced Dorelia to her brother Augustus who formed a ménage à trois with her and his wife, Ida Nettleship. It has been suggested that John herself had romantic feelings towards Doreila. Comparing this to Nude Girl, there is a warmness to this painting of Dorelia. Her gaze is soft but alluring and there is a vulnerability in her pose. Augustus John used Dorelia as a model for many artworks, but this painting by Gwen offers an affection towards Dorelia that I don't see in her brother's work.

Interpretations of Gwen John's life have altered significantly over the years – from seeing her as a recluse and overshadowed by her brother, to a more feminist perspective where her independence is celebrated. However, there is more work to be done: a queer lens allows us to understand John's independence and perceived reclusivity in a more nuanced way.

Exploring John's relationships helps to diversify the narratives of multiple gender attraction. Often bisexual+ people are portrayed as selfish or greedy, unable to control their sexual attraction because the opportunities for romantic and sexual relationships are considered endless. John had a series of strong emotional attachments to both men and women within her life and for many, we do not know how reciprocated these feelings were. Her relationship with Rodin was monumental both personally and creatively, but by making this relationship more significant than other relationships, we run the risk of erasing her multiple gender attraction and continuing to promote heterosexuality above all else.

Tabitha Deadman, Whose Heritage? Research Resident at Culture&

Read the other stories in this series, examining the artists Dora Carrington (1893–1932) and Marie Laurencin (1883–1956) in the context of multiple gender attraction