Art history's mythic world of bohemia has never lost its allure. Crossing borders from London's Fitzrovia and Soho, to Montmartre and Montparnasse in Paris, we know it as a place where excessive talent was matched by excessive lifestyles, inhabited by male geniuses and their beautiful female muses.

I want to argue here that the bohemian world as it was originally lived was more nuanced than the stories that dominate today, and that if we pay attention to those women caught up in – and sometimes overwhelmed by – the later myth, we can explore the ways in which the complexity of their lives has been hidden in its service.

Bohemia in London at the beginning of the twentieth century was, we are often told, epitomised in the figure of one man: Augustus John (1878–1961). He became as famous for his persona as for his dazzling talent: sexually promiscuous, long-haired and wearing earrings and a wide black hat, his was a mash-up of Parisian left-bank style and fancy-dress Romany. If we consider the facts of his sister Gwen John's life, we might easily label her a bohemian too.

Denizen of artists' studios in Paris where she painted, modelled and socialised, she was the lover of a great artist herself – Auguste Rodin. But, perhaps mindful of the perceptions and pitfalls already facing women who lived like this, she was careful to describe herself, in her letters to Rodin, not as 'bohémienne' but 'artistique'.

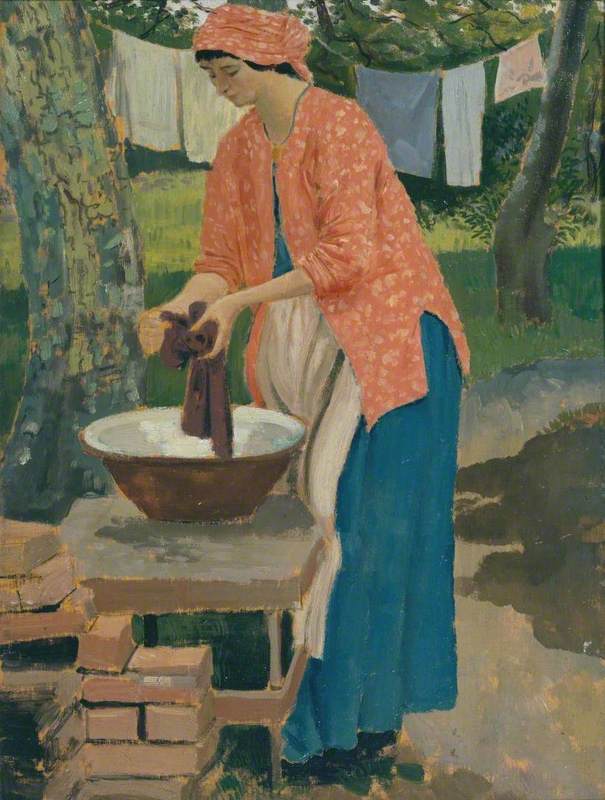

By contrast, Gwen John's (1876–1939) friends and contemporaries, Ida Nettleship, who married Augustus, and 'Dorelia' (real name Dorothy McNeill), who became his mistress, had both studied art. However, following their connection with Augustus, each lived a much more conventionally feminine existence centred on caring for his children. Despite this, they were labelled bohemians. For women, it seems, having a bohemian identity was a complex affair. You could refuse to be thought of in those terms, though you might behave, as Gwen John did, as a textbook example, even living in a Parisian garret.

Or you might, like Ida and Dorelia, spend your days tending family and home, looking after your man, but still be firmly placed in that category.

Why did Gwen John make the distinction and refuse the label? The answer, perhaps, lies in what had happened to the idea of bohemianism by her time, and by the dangers that this warping of the original model could pose for women then.

The idea of the bohemian artist as outside society, not subject to its rules, could seem to offer women unheralded freedoms, but this was a world in which they had fewer protections and much less power than today. The stories of two women who were destroyed – Ida Nettleship John and Dolly Henry – bear this out.

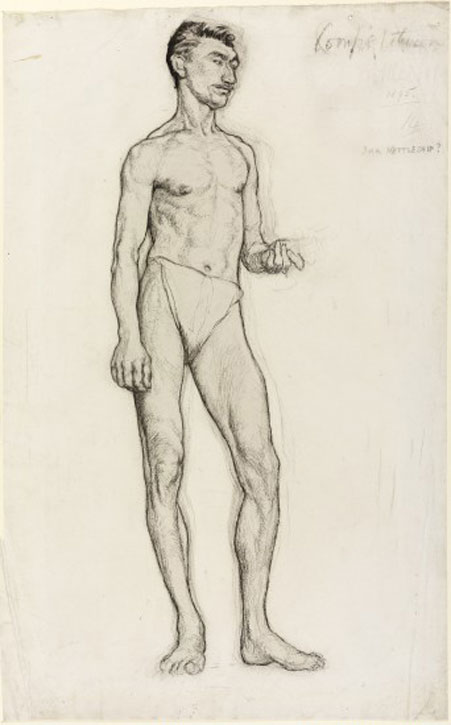

A Study of a Nude Male Figure

1895, black chalk by Ida Margaret Nettleship (1877–1907)

Nettleship, as she was at the Slade, had been a promising student, but her marriage to Augustus John put paid to her work. His art came first, always, and she died at 30 after giving birth to her fifth child. In his memoir, Chiaroscuro (1952), Augustus made no mention of her, although her own vivid letters have finally been published in Ida John, the Good Bohemian (ed. Rebecca John and Michael Holroyd, 2017).

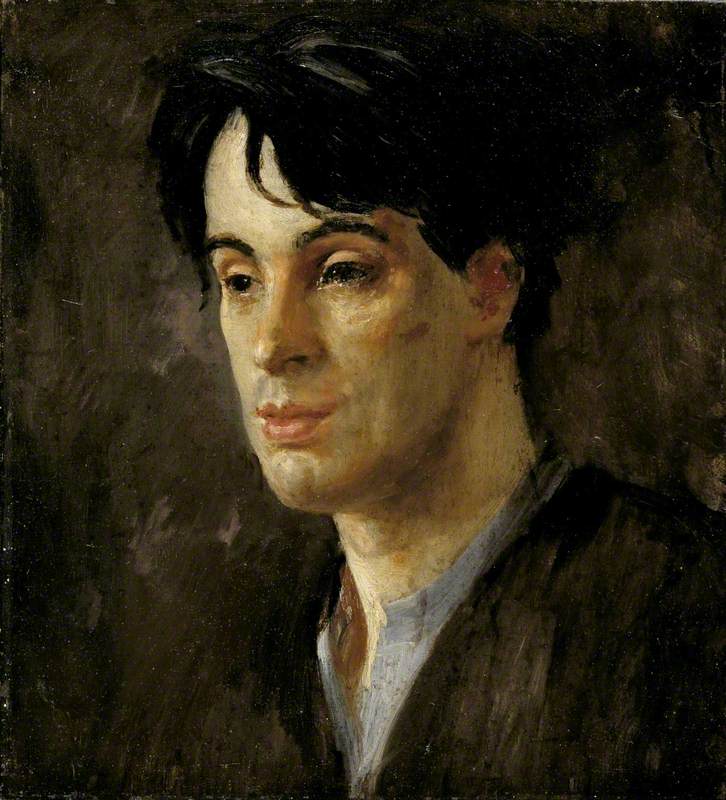

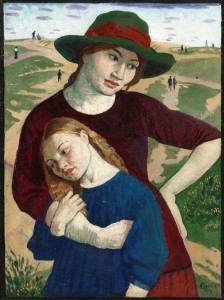

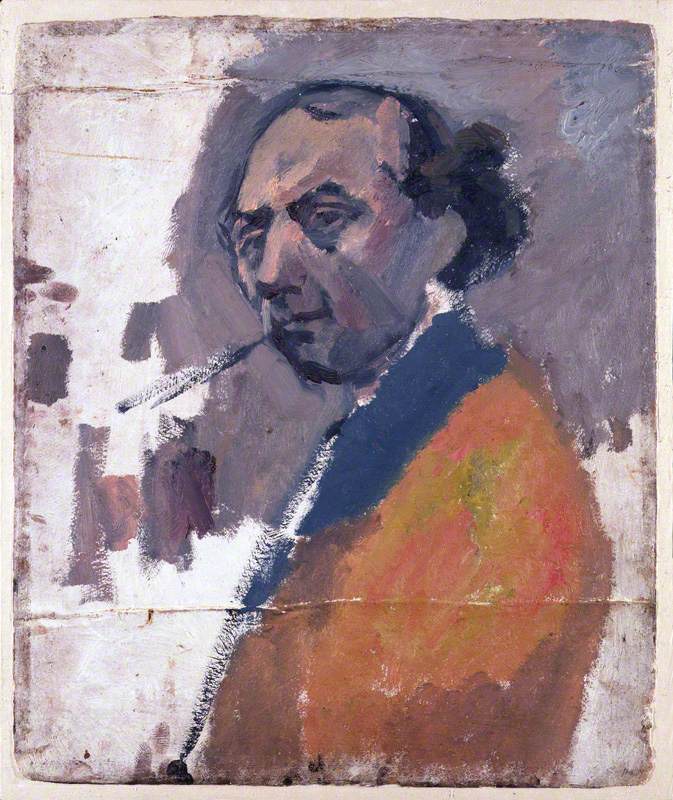

Ida John (c.1877–1907), Pregnant

1901

Augustus Edwin John (1878–1961)

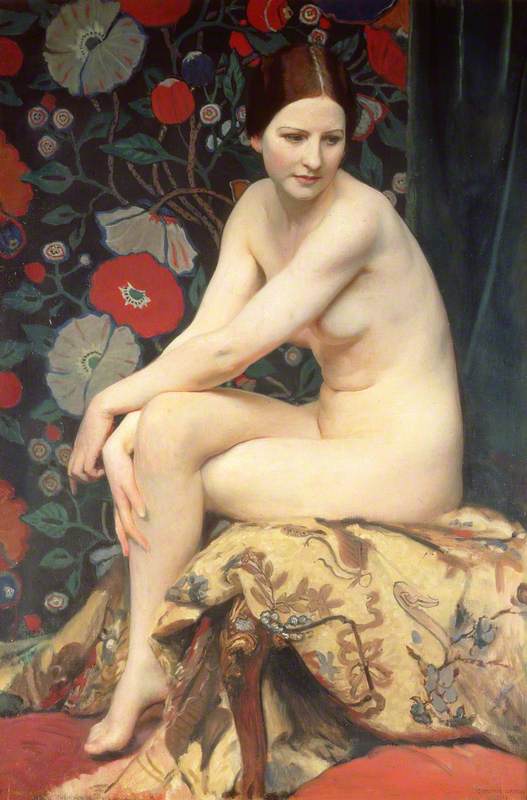

Dorothy 'Dolly' Henry, lover and model of John Currie (1883–1914), also a Slade student, was murdered by him in a jealous rage, having been portrayed by him as 'the witch', and was posthumously vilified by his friends.

This point of view dominated for many years, but has recently been challenged by the emergence of other versions of Dolly: her family's memories of her as a loving sister, Laura Knight's account of her living in fear of Currie's violence, and George Clausen's poised and thoughtful portrait. Clausen felt so moved by her death that he helped to pay for her funeral.

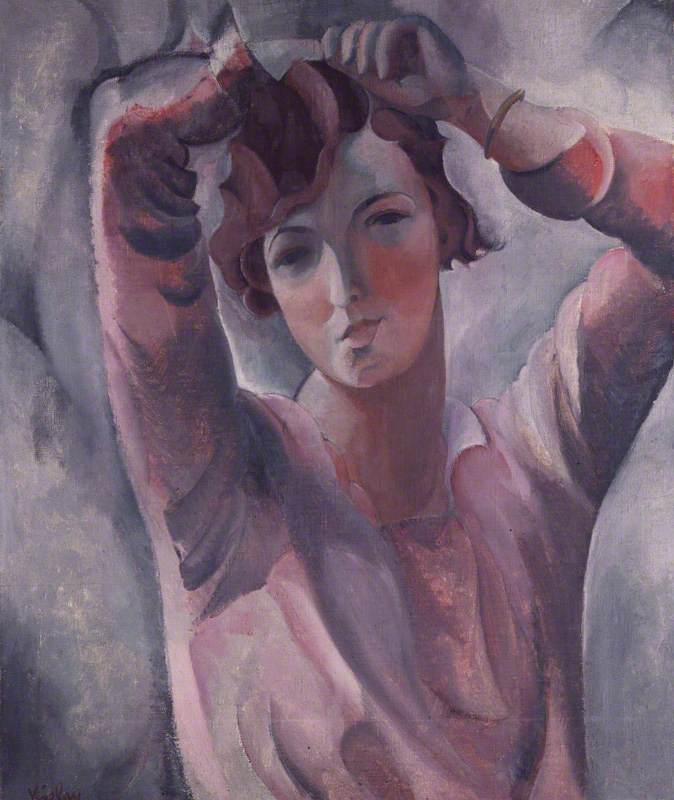

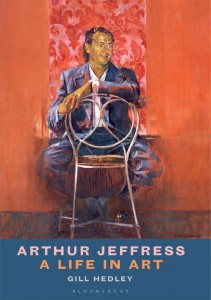

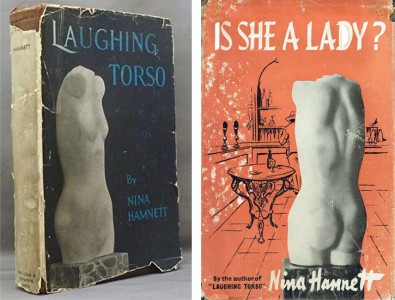

Even a woman who managed to inhabit and manipulate the image of the bohemian to her own advantage – Nina Hamnett (1890–1956) – was, in some senses, stymied by the myth she created. Her best-selling memoir, Laughing Torso (1932), described a life in artists' cafes and studios, modelling and also making her own work, that Gwen John might have found familiar.

Yet in playing up her identity as the 'Queen of Bohemia' the focus on Hamnett's art was lost, and the richness of her life and work reduced: artist, designer, author, public figure, model and lover of men and women. We will have a rare chance, when museums and galleries reopen after the current crisis, to see a new exhibition of her work at Charleston.

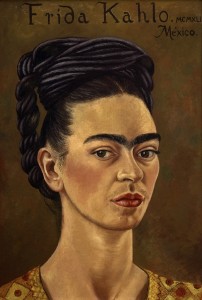

The original Queen of Bohemia, before the title became overshadowed by its later interpretation, was a woman who had made her own agency the guiding light of her life: the French writer, George Sand (1804–1876).

Rather than signalling a hackneyed return to old gender divisions, bohemianism, as lived by Sand, meant leaving her husband and family, moving to Paris, and using her time to write bestsellers and take lovers. In enjoying city life, her propensity for wearing masculine clothes was often described as a disguise that allowed her to pass unhindered, but must in fact have been a striking sight in the circles she moved in.

Bohemianism, then, had originally offered women a refusal to be bound by conventional ideas of how they might live, and an idea of the self that was centred on their work and choice of partners without the duties of married life. Even though it was too often later co-opted as a return to the old sexual hierarchy carefully disguised in eccentric clothing and café posing, at its best and at its origin it was a way of thinking beyond the limitations that had particularly repressed women.

The poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Sand's contemporary, had managed to escape from the full weight of the dark side of Victorian femininity – a restrictive parental home and 'treatment' of her ill health that was, in reality, infantilising control. Browning admired and understood the full liberating force of Sand's bohemianism. As she wrote in her 1853 poem, To George Sand: A Desire:

Thou large-brained woman and large-hearted man,

Self-called George Sand! Whose soul, amid the lions

Of thy tumultuous senses, moans defiance

And answers roar for roar, as spirits can!

Alicia Foster, curator

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.