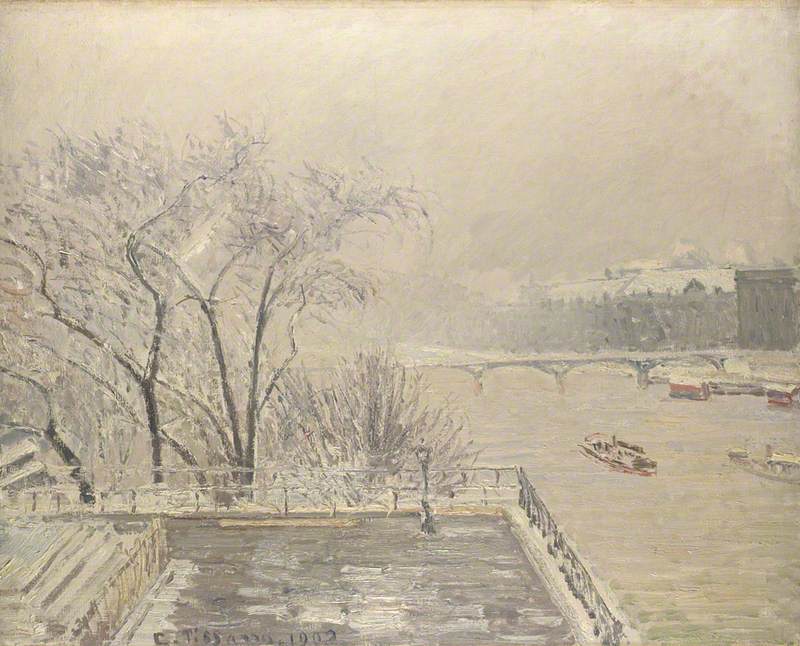

In his 1886 novel Soi, Paul Adam describes an exchange between a painter called Vibrac and a rich, conservative woman, Marthe Grellou. Vibrac, whose character Adam is based on the Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro (1830–1903), expounds his radical vision for painting. As he paints snow from a veranda, Marthe sees him reaching for colours other than white, and accuses him of 'rich exaggeration'. He responds: 'When I look at snow, I see pinks and lilacs in the shadows, and these shades are everywhere.'

Snowy Landscape at Éragny with an Apple Tree

1895

Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

Vibrac's reply brings to mind this small landscape painted by Pissarro from his studio window in the village of Éragny-sur-Epte in northern France, where he lived for 20 years before his death in 1903.

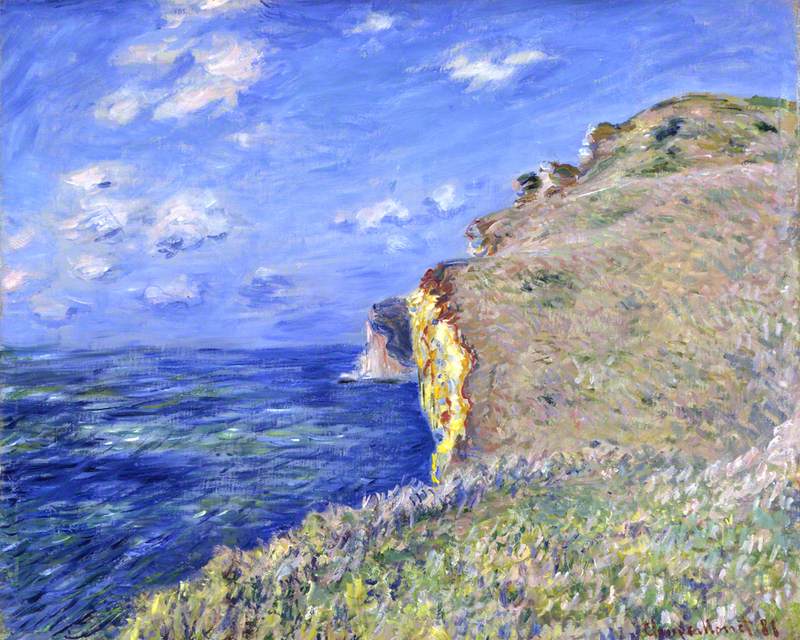

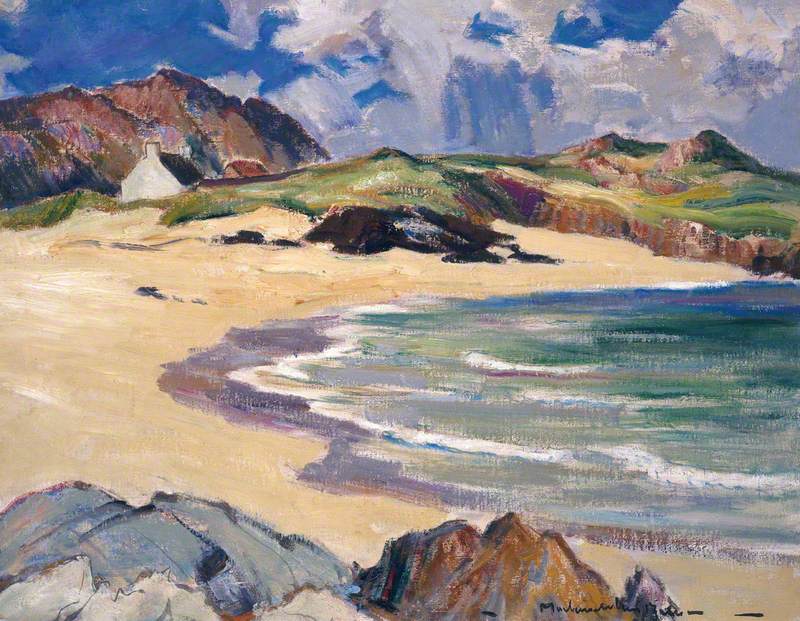

Look closely at The Fitzwilliam's Snowy Landscape at Éragny, with an Apple Tree, and you'll struggle to find much pure white. Despite the luminous tone across the picture – like the even glow of light hitting virgin snow – the colours, pure and mixed, vary hugely. From the yellow of the sun and its reflections on the snow on the meadows, to the violet and earthy-green branches of the most prominent tree, the grey-blue of the distant buildings and spire in the small village of Bazincourt, and the pinks and lilacs in patches across the picture from foreground to sky, Pissarro creates tremendous chromatic subtlety from just a few paint tubes.

From the moment Pissarro began renting the house and farm at Éragny, 70 kilometres from Paris, in March 1884, he was enchanted. 'I haven't been able to restrain myself from painting, so beautiful are the motifs that surround my garden,' he wrote to his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel.

Éragny sous la neige (Éragny under snow)

Camille Pissarro

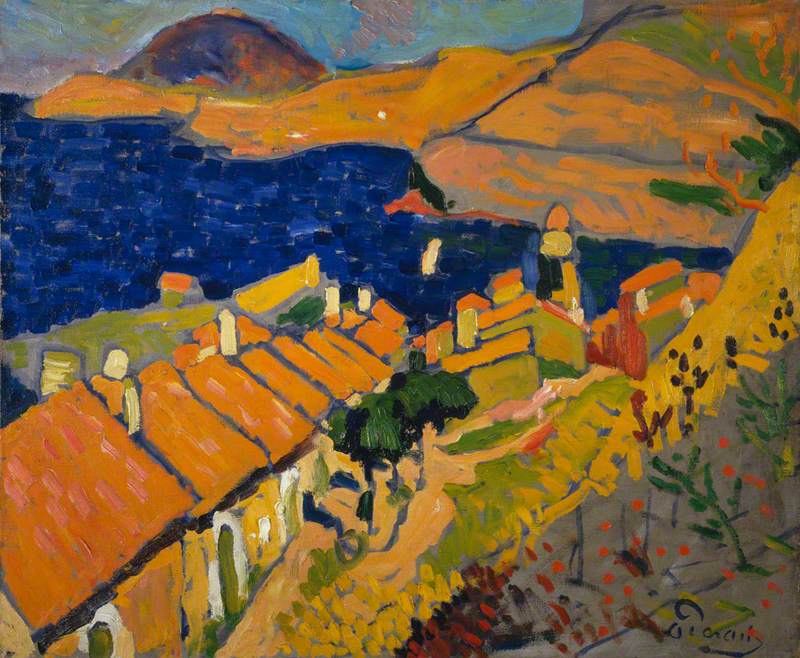

Over the following two decades, he repeatedly painted views from the farm and within the local towns and villages, as well as workers in the fields around Éragny – images which reflected his anarchist convictions and desire to illuminate the struggle of rural labour. But no motif preoccupied him more than the view of Bazincourt.

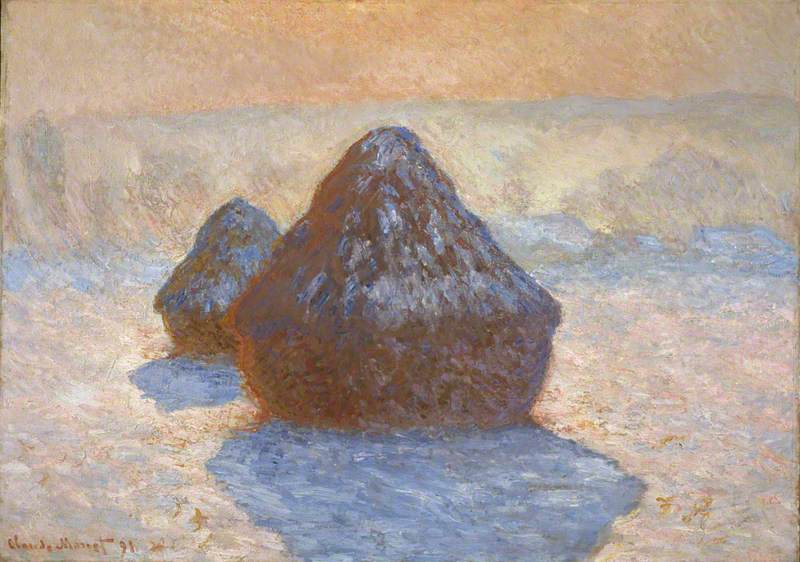

The paintings in his series were not as sequential and programmatic as his friend Claude Monet's great haystacks and cathedrals but he was compelled to return to the landscape again and again. 'I was afraid that repetition of the same motif would be tiring,' he wrote to his son Lucien Pissarro at Christmas in 1891, 'but the effects are so varied that everything is completely transformed, and then the compositions and angles are so different.'

When he painted this winter scene in 1895, he had not long become the owner of the Éragny farm, after a decade of renting. It had been put up for sale and while Pissarro was on one of his regular trips to London his wife Julie wrote to Monet – who had begun to sell vast numbers of works at high prices through Durand-Ruel – to ask him for a loan of 15,000 francs to buy the property. Monet agreed; Pissarro was horrified. Not only was he an anarchist and against being a landowner in principle, but he was aghast at owing his old friend cash.

Morning Sunlight on the Snow, Éragny-sur-Epte

1895, oil on canvas by Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

Indeed, even though he was having annual shows with Durand-Ruel by then, the greater success of his peers clearly bothered him and caused him to doubt his work.

In a letter to Lucien written in February 1895, around the time he painted Snowy Landscape, he expressed his personal worries and reflected on the mixed reception for his and his friends' paintings, even 20 years after the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874: '…even in Paris where I am known, known by everybody, people scorn or don't understand them,' he wrote. 'Moreover, as a result of this incomprehension I myself am ending up wondering whether my work isn't poor and empty, without a hint of talent. It is said that money is scarce, but that is only relatively true; doesn't Monet sell his work, and at very high prices, don't Renoir and Degas sell? No, like Sisley, I remain in the rear of the Impressionist line.'

His insecurities might have something to do with the major shifts of the previous decade – his experiments in the late 1880s with the Neo-Impressionism of Paul Signac and Georges Seurat. The more conceptual, scientific approach meant his production had slowed. Durand-Ruel had even fewer paintings to sell and was experiencing financial difficulties. Pissarro's letters from Éragny in that period are full of money worries, even after he had rejected Neo-Impressionism and returned to the more conventional – and saleable – Impressionist style of Snowy Landscape.

Farm at Montfoucault: Snow Effect

1874–1876

Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

He was also preoccupied with his health through the 1890s. Earlier in his career, he had, like all the Impressionists, committed to painting outdoors, but from the late 1880s onwards, he rarely painted en plein air even in spring and summer, because he was told to avoid dust and wind. He had an eye condition – chronic dacryocystitis, inflammation of the tear ducts – which caused him great distress and forced him indoors. An engraving by Lucien depicts Pissarro on the second floor of the barn at Éragny, where he would look through a west-facing window to paint views like Snowy Landscape.

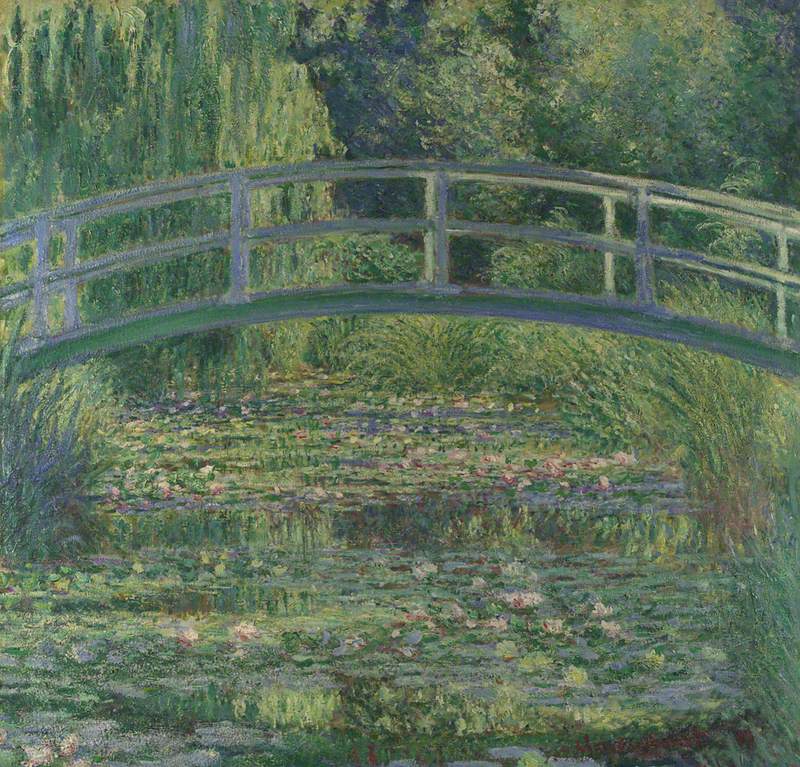

He had seemingly relished painting out in the snow in his earlier years. His first forays into wintry scenes were at the turn of the 1870s, where he and Monet stood together just in front of his house in the Parisian suburb of Louveciennes and made paintings of the road of the Versailles.

Wherever he went, he relished the chance to paint snow, and winter scenes were also popular with collectors. A year after painting Snowy Landscape, he wrote to Lucien: 'My pictures are advancing. I have eight things going, I am waiting impatiently for snow.'

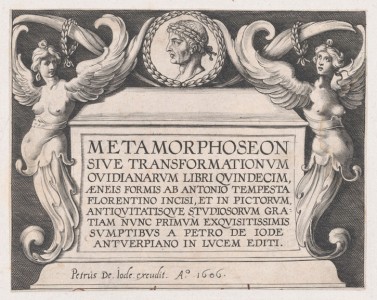

But another reason he may have relished painting hibernal scenes was the Japanese prints that were such a cornerstone of the Impressionist movement, many of them evocatively picturing snow.

Pissarro was as effusive as many of his peers. He described the 1893 exhibition of 300 prints by Hiroshige and Utamaro at Durand-Ruel's Paris gallery as 'admirable', adding: 'Hiroshige is a marvellous Impressionist. Monet, Rodin and I are enthusiastic about the show. I am pleased with my effects of snows and floods; these Japanese artists confirm my belief in our vision.'

Snowy Landscape evokes the elegance and graphic power of those Japanese prints, in the overall simplicity of the composition and in those curving branches of the central apple tree, which appears almost to dance in the breeze.

A man on horseback in the snow

c.1840–1842 woodblock print by Hiroshige (1797–1858)

In reflecting the influence of Japanese prints, in its attention to the fleeting, subtle effects of light and in its rapid brushwork, this modestly scaled picture packs in many of the hallmarks of Impressionism. It also reflects an artist in a rich vein of form, having cast off the restrictions of his experiments with Neo-Impressionism, and thrown himself back into a flowing, speedy response to the landscape.

Whatever his worries about money, his health and his reputation, in his Éragny studio – looking out over his orchard, the meadows and the valley to Bazincourt, on the low hills beyond – Pissarro was in his element.

Ben Luke, writer and critic