The brightest comet of the year, Comet 460/Wirtanen – otherwise known as the 'Christmas comet' – comes closest to Earth (that is, 7 million miles away) on December 16th, and it will be so bright that it should be visible to the naked eye. If you miss it in December though, fear not, for although it will come closest to us this month, Comet Watch predicts that it should still be able to be spotted until early next year through binoculars.

This month’s comet will also be accompanied by the strongest meteor shower of the year, the Geminids, which are active every December. For the best chance to see these fascinating phenomena, it is advisable to find a place that is as dark as possible, far from light pollution, and gaze skywards.

... such was the brilliance of this comet that it helped to spark enthusiasm for astronomy among the general public, as well as inspiring artists and poets

Hungry to show how artists have captured these bright entities in the great night sky, I’ve trawled the archive – as well as the night sky – for comets. If you miss seeing the comet completely, you could instead delve into the archive of Art UK to see how artists have captured this kind of celestial entity. If you are lucky enough to see the Christmas comet, I would still advise feasting your eyes upon these artworks to see how comets have sparked the imagination.

Comets – glowing balls of ice and dust orbiting the sun – sometimes referred to as ‘dirty snowballs’ or ‘snowy dirtballs’, and literally translating as ‘long-haired stars’, have inspired artists throughout the ages. They gather within them not only ice, rock and dust, but also centuries of mythology, with much paint and ink having been spilt attempting to capture their glory.

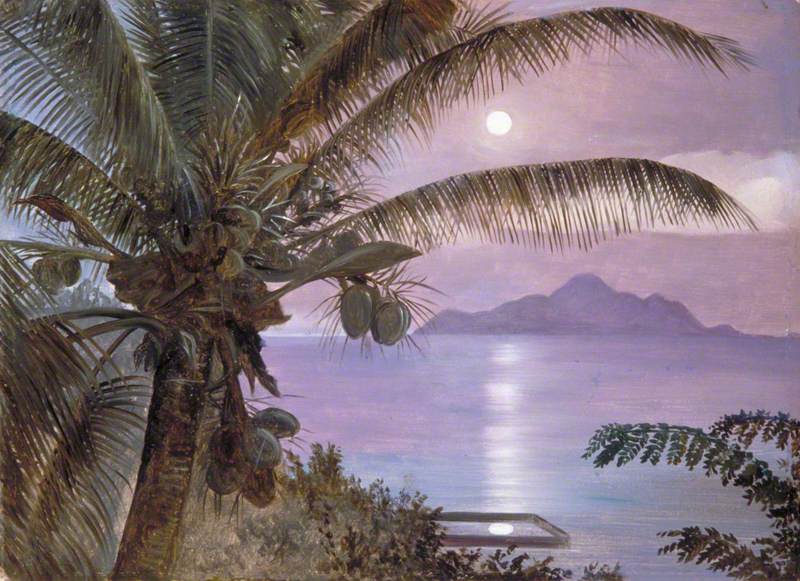

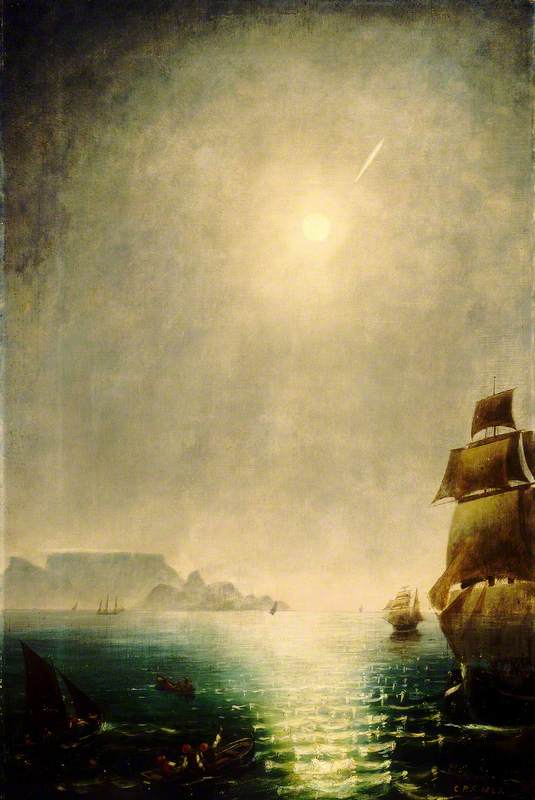

The Great Comet of 1843 fired many artists’ imagination. To qualify as a 'great comet’, one has to be exceptionally bright, and indeed this one was so bright that it was visible by day as well as by night. Paintings capture this well. The astronomer Charles Piazzi Smyth depicted his eyewitness account of a night-time view of the comet in the painting The Great Comet of 1843. The view is most likely from where he witnessed the comet at the Royal Observatory in the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, showing Table Bay with Table Mountain glowing red in the distance. The vastness of the natural world is set into high relief by the smallness of the human being we can see in the painting, viewing the sky, and the same colour as the sunset, suggesting a merging of mankind and nature.

Daylight View over Table Bay Showing the Great Comet of 1843

1843

Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819–1900)

Charles Piazzi Smyth also captured his daytime sighting of the comet in the equally powerful painting Daylight View over Table Bay Showing the Great Comet of 1843, with the comet a hugely haunting presence in the sky. The comet’s intensity of light – as well as the length of its tail – broke records, and both the light and length of this comet are brilliantly shown.

One of the most striking paintings is Donati's Comet by James Poole, which excellently captures the reflection of the comet in a lake and hints at its extraordinarily long tail. Named after the Italian astronomer who first observed it, such was the brilliance of this comet that it helped to spark enthusiasm for astronomy among the general public, as well as inspiring artists and poets, including Thomas Hardy who recollected seeing the comet in his poem ‘The Comet at Yell’ham’.

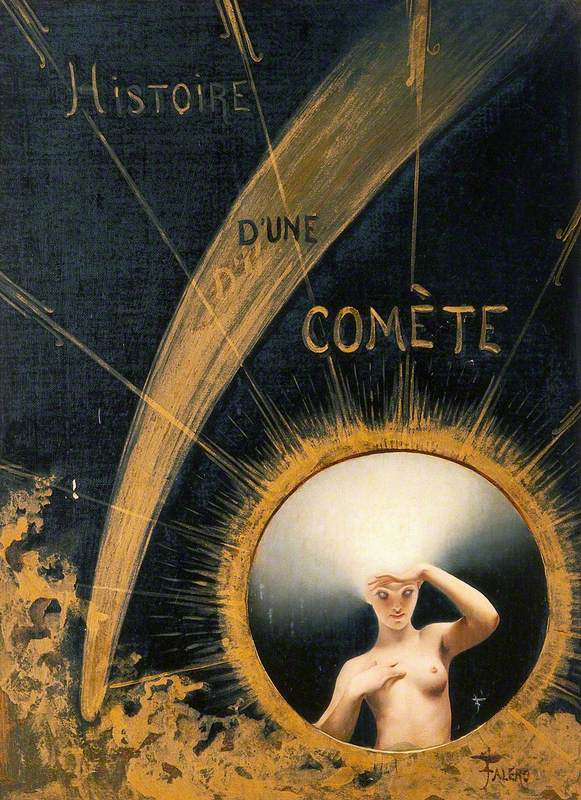

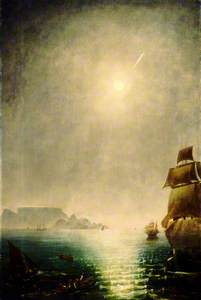

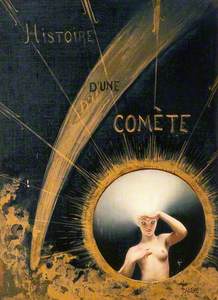

Other paintings of note include A Comet by John Everett (1876–1949), which uses paint skillfully to show the speed of a comet in a cloudy sky above a stormy sea, and also Story of a Comet by Luis Ricardo Falero (1851–1896).

Comets have been feared as portents in some cultures, as portrayed in the ominous painting The Ides of March, 1883. The painting illustrates Act II, Scene II of Julius Caesar, when Caesar's wife Calpurnia warns him to view the comet they see as an omen and to stay away from the Senate on the Ides of March, the 15th day of the month, for fear he will be murdered.

The painting Study for 'The Ides of March' compellingly captures the eerie green light of the comet and an outer landscape so powerful that no human civilisation can withstand it, despite the grand marble columns and the palatial Roman house. The expression 'Beware the Ides of March' is first found in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, 1601. The line is the soothsayer's message to Julius Caesar, warning of his death.

‘Night, most glorious night, thou wert not made for slumber’

1874

John MacWhirter (1839–1911)

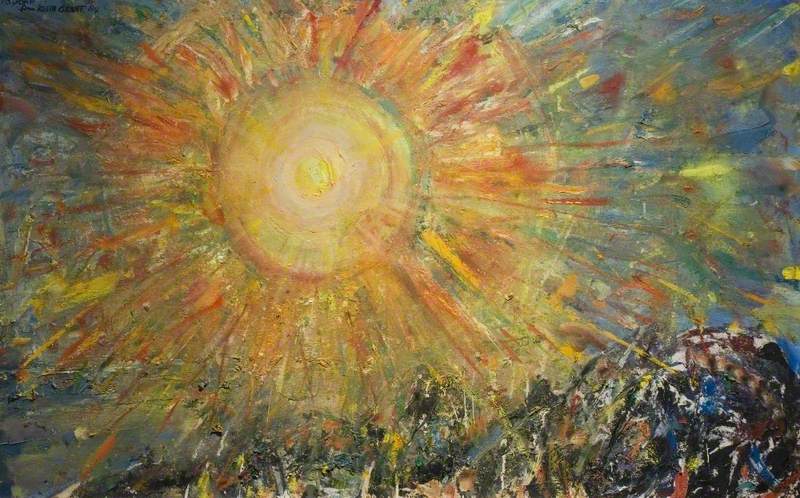

Lord Byron's lines, 'Most glorious night! Thou wert not sent for slumber!', the painter John MacWhirter (1839–1911) well knew, choosing this title for one of his artworks.

Hopefully, this journey through comets past and present has inspired you to take a few moments to step outside and gaze heavenwards into what is promising to be a most spectacular night sky.

Anita Sethi, journalist, writer and critic