The pain started when I was 12 years old, in a biology lesson where I was escorted to the school sick room and collected early by my mum. Since then, an intense burning in my lower abdomen has impinged on life in ways too complex and multiple to list. For years I didn't have a name for it either. Endometriosis would only enter my vocabulary at the age of 27, bringing with it a TENS machine and a wave of reassurance that whatever dark anger resided inside of me was at least a shared one.

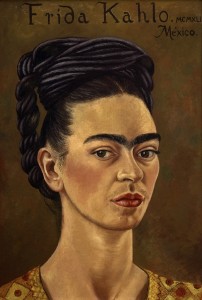

During those years without a diagnosis, a friend invited me to see a Tracey Emin retrospective 'Tracey Emin: 20 Years' at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh. Despite not sharing Emin's past political beliefs, the show had a profound effect on me.

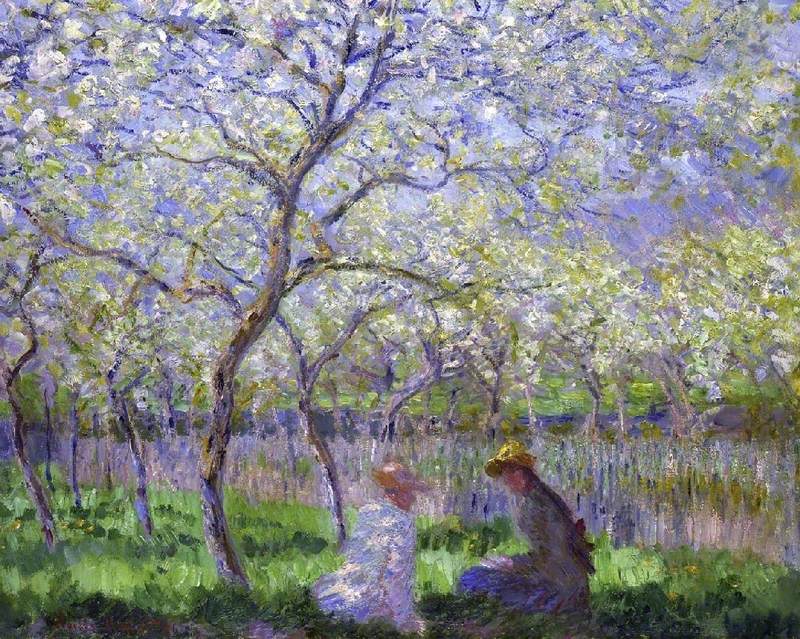

Being young and unaccustomed to art, I'd always equated artistic achievement with grandeur. But here were works of a slight and tender variety: a room full of miniatures – drawings, sculptures and found objects – similar to those I'd always collected and stashed around my home; a series of tactile wall hangings, made from pieces of scrap and sewn together with the imperfection of the human hand.

The only other postmodern works I'd ever seen were colossal Anselm Kiefer works at the White Cube, whose Wagnerian symphony made a broken lullaby of these tiny things.

View this post on Instagram

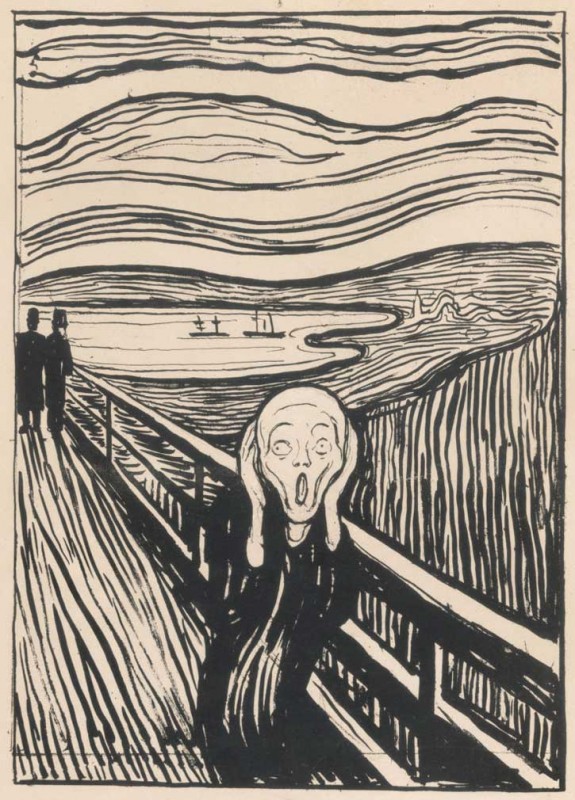

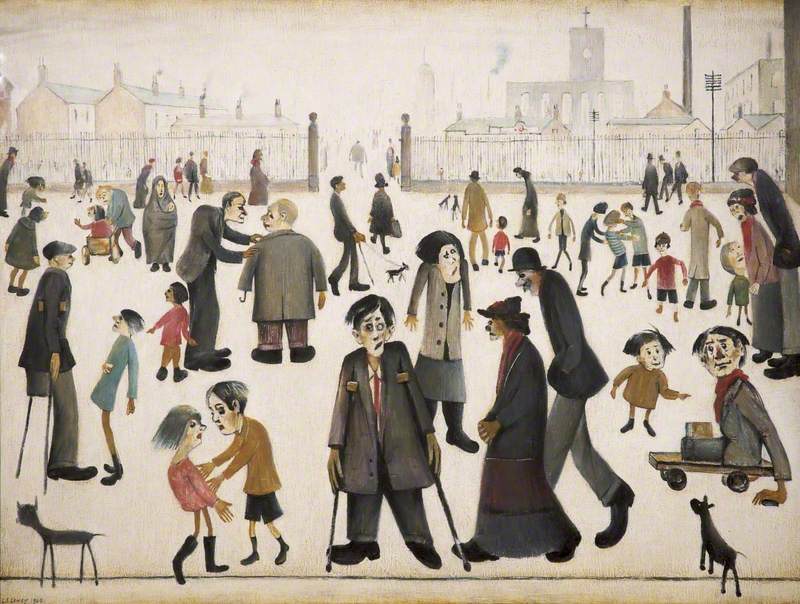

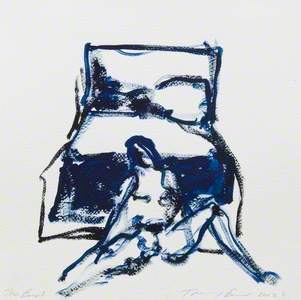

One room in particular, devoted to the botched abortion suffered by Emin, struck me on an even deeper level. Between the surgical robes on display, were drawings of figures – not women, not even people, given the lack of detail – but hollow, empty outlines of a prehistoric simplicity. These were figures distorted by pain, their abdomens mired by thick dark lines and explosions of ink. They were often bent double on the floor, or writhing in agony.

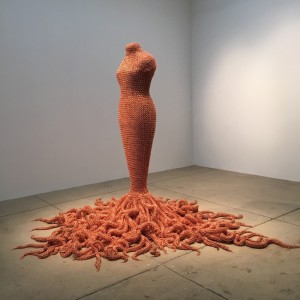

Later, I would discover the artist Louise Bourgeois and experience a similar sensation when looking at her red ink drawings and contorted figures, which convinced me that she must have also experienced a similar pain.

View this post on Instagram

I hung about in that room for a long time, morbidly enjoying the sensation of seeing my own experience translated onto the walls of the gallery. I knew nothing of Emin's biography, and still don't think it much matters. What she had captured was the dark rupture that occurs in the hidden depths of so many women. Women who experience miscarriage of course, but women who also experience anatomical issues long neglected by the medical establishment, the millions of us who suffer from internal bleeding, ovarian cysts, ectopic pregnancies and gender misalignment. These were works of a libidinous and Freudian variety, that captured the agony of sex, and not just intercourse, but in the deep, throbbing, agonising swell that defines so much of our lives and our identities.

These grotesque apparitions have stayed with me for many years, through the hundreds of instances when I've been bent double on the floor and crying out in pain. During the times when I've been forced to dismount my bike or stop running and hide in a bush until the pain had passed like a wounded animal, while the blood clots came thick and fast. Or lay on the bathroom floor awaiting the arrival of an ambulance.

Endometriosis is still not recognised as a formal disability – a travesty to those of us who suffer from extreme cases. It is a condition that affects 1 in 10 women in the UK, but who are nevertheless unable to vocalise their suffering to their employers, and who must still suffer a blank stare from many of their loved ones and, in many cases, even from the medical professionals entrusted to care for them.

Just two weeks ago, I was admitted to hospital with pains that I've been told by my fellow sufferers eclipse even labour contractions, only to be met by a doctor who told me to simply rest up, wear a heat pad and maybe try some light exercise.

For 20 years I've been giving birth to my own pain, knowing that with each cycle my chances of fertility are diminishing, and as the internal bleeding continued to twist and distort my internal organs, pushing them ever closer to obsolescence.

View this post on Instagram

In such moments, my mind always travels to those places where pain relief does not exist, in some parts of the world and in the not-so-distant past. How women who have suffered with this condition have been forced to do so without support or guidance. When I am met with ignorance, I picture us of all reduced to the size and stature of Emin's miniature figures; featureless and all of our personalities eclipsed by the roaring pain and its ruinous array of anxiety, stress and fatigue.

How, in one simple drawing, dashed off so quickly and in the throes of grief and agony, had Emin been able to capture so much and deliver it so forcefully?

Nathalie Olah, journalist