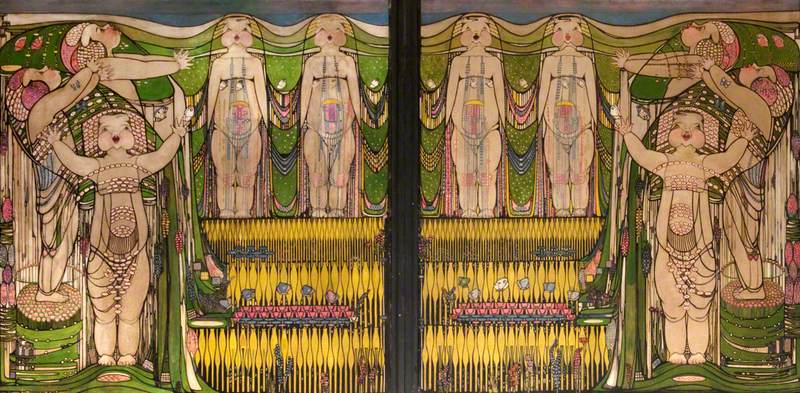

A muffled sound of the church organ coupled with the holy, angelic voices of the mass choir, a sound that continuously resonates in my memory. My family and I situated ourselves on the opposite side of the church doors as an overwhelming feeling wracked my young frame. Every Sunday I stood in front of those wooden swing doors of the sanctuary only to be met by Sis. Mitchell’s warm smile as we were lead to our seat on an elongated church pew. From time to time, I would shut my eyes and draw in the overpowering scent of perfume radiating from the collar of the head Deaconess’s crisp white suit.

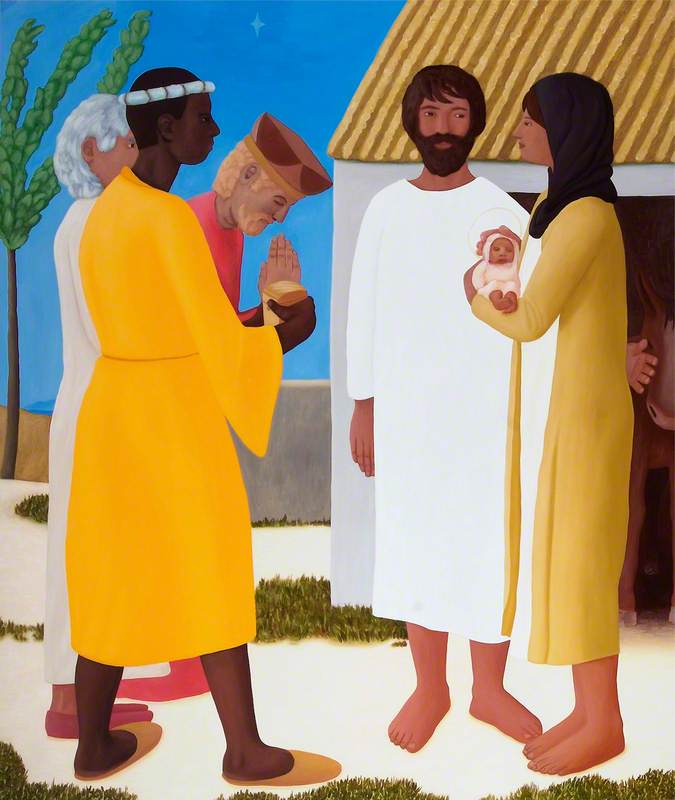

20 years later I find myself across the Atlantic reliving these most formative childhood memories of my Southern Baptist upbringing through the paintings of self-taught African American artist Clementine Hunter. Her paintings take me back to those early Sunday mornings where I would find myself in a historical safe haven where time, trials and tribulations were no longer my own. In a mere blink of an eye the 'secular' or outside world was no more; my refuge was in that anointed building. This artwork reminds me that that journey to church transcended a simple arrival to a destination, rather this journey represented the taking part and a continuing of an incredibly rich cultural history; most importantly my cultural history. Adorned in our Sunday’s best, my community met in that blessed shelter with the same objective, to be blessed and highly favoured.

The nostalgia provoked by Going to Church has allowed me to further appreciate and fully recognise those unique childhood memories of the coveted Sunday morning in the South. Like Hunter, I grew up in the south east region of the charming state of Louisiana; in fact my childhood home is a few hours drive from Melrose Plantation where Hunter spent a majority of her life. As a fellow Louisianian, I find her work riddled with an overwhelming familiarity that embodies a certain experience of a beyond or as 'us Southern folk' call it, a 'yonder'.

Going to Church presents the viewer with 12 loosely painted flat figures synched in a purposeful stride towards the church; a church elder or 'mother of the church' leading them onwards and upward towards something greater. I find myself continuously revisiting Hunter’s unique representation of this classic Southern scene and immediately feel not only as if I have been there before, but as if I am still there in this current moment. I have been to Hunter’s pastoral landscape not once but on several occasions. However, my nostalgia surpasses any reliving of my physical occupation of that exact space on that makeshift dirt road but rather a nostalgic experience of a space beyond my full understanding.

The 12 precious figures march from east and west, ascending upwards to escape the burden of 'this old world', even if for a brief moment in time. The forward facing 'saints of the church' line up, one behind the other, one foot in front of the other for what is the most sacred part of the week; a chance for our weary physical bodies to get as close to the divine as possible. Moments such as these are pertinent and so cherished because they provide(d) the community with this shared experience. This communal gathering not only makes a Sunday morning church service powerful but also incredibly empowering. Going to Church allows Hunter’s audience to transcend beyond the physicality of a painting and taps into a part of spirituality that written and verbal language will continually fail.

Hunter’s genuine message of a joyful passage from the secular to sacred has provided us with an authentic and first-hand historical glimpse into the pillar of the black community. The 'black church', as it is often called, has traditionally been a place of healing, shelter, and solstice; Hunter has flawlessly encapsulated its impact by providing a precise account into one of the most cherished aspects and driving force of my community and we are thankful.

Ashleigh Barice, writer