Scotland's most celebrated architect spent his final years painting watercolour landscapes in French Catalonia thanks, in part, to his friendship with an unsung artist called Rudolph Ihlee (1883–1968).

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) was in the doldrums when he left London with his artist wife Margaret (née Macdonald) in 1923 to settle in the south of France. Architectural commissions were drying up and money was in short supply.

Based in Collioure, Ihlee, who had left London the year before, encouraged them to sample the Mediterranean lifestyle. And the promise of sea, sunshine and a cheaper cost of living proved irresistible.

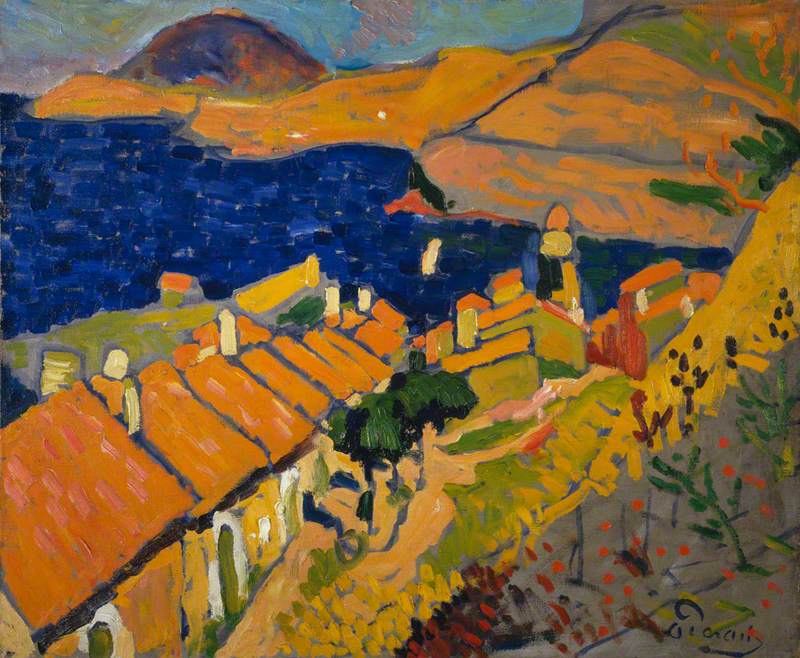

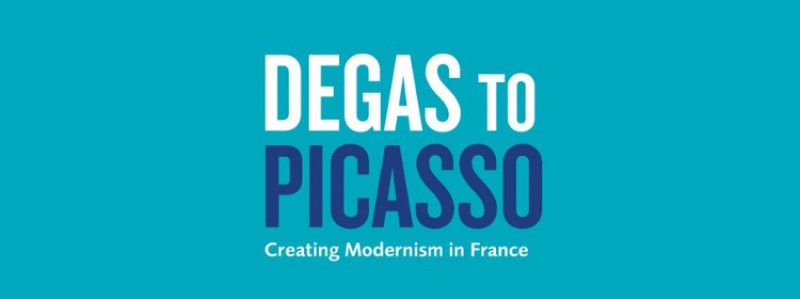

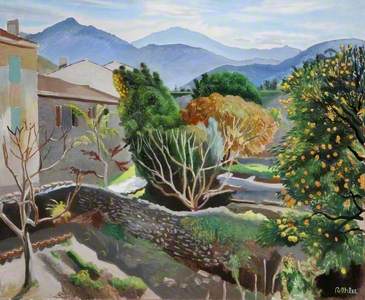

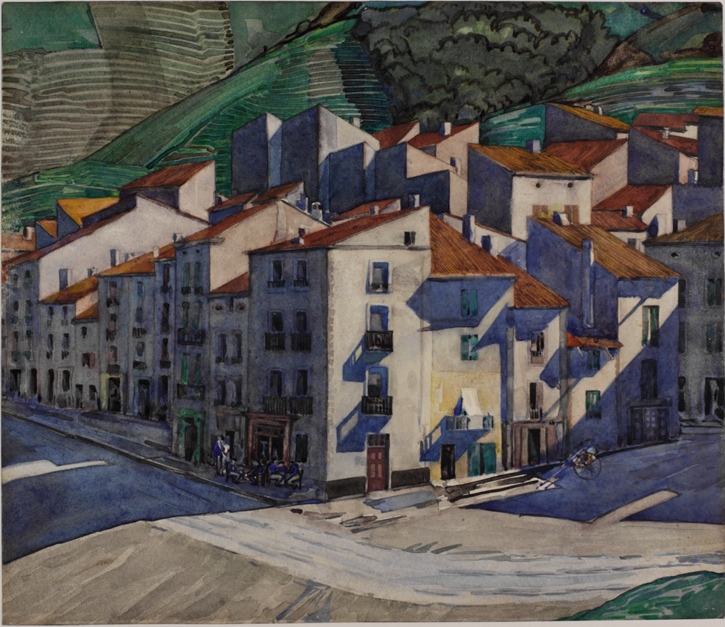

© the copyright holder. Image credit: The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

Fort Precincts, Collioure 1927

Rudolf Ihlee (1883–1968)

Hunterian Art Gallery, University of GlasgowFor much of the next four years the couple stayed at the Hôtel du Commerce in Port Vendres within walking distance of Collioure. It was one of the happiest periods of their lives.

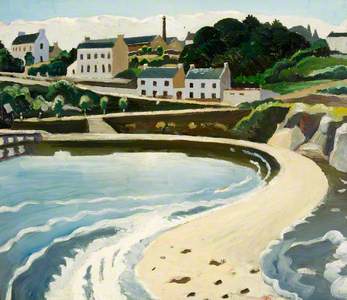

Image credit: public domain

Liner at Port Vendres

c.1920, postcard. Hotel du Commerce, where the Mackintoshes stayed, is on the extreme right

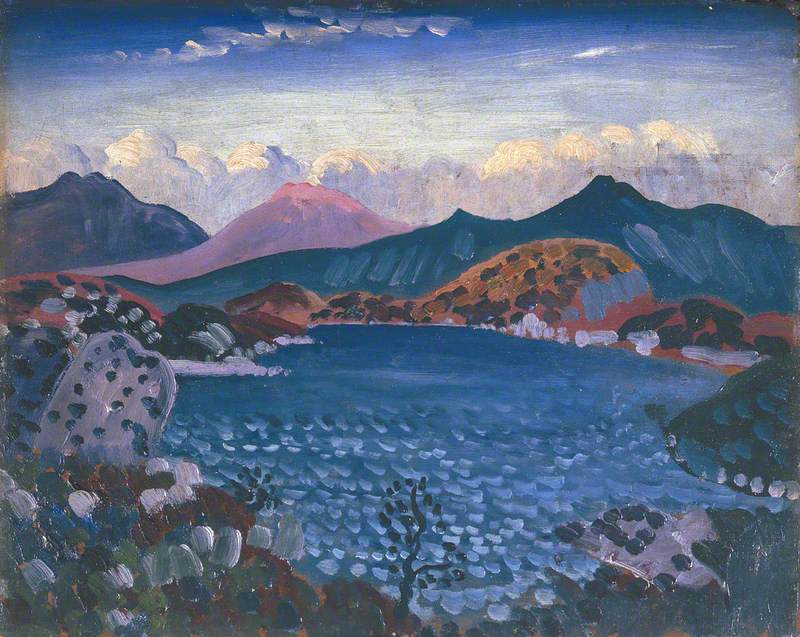

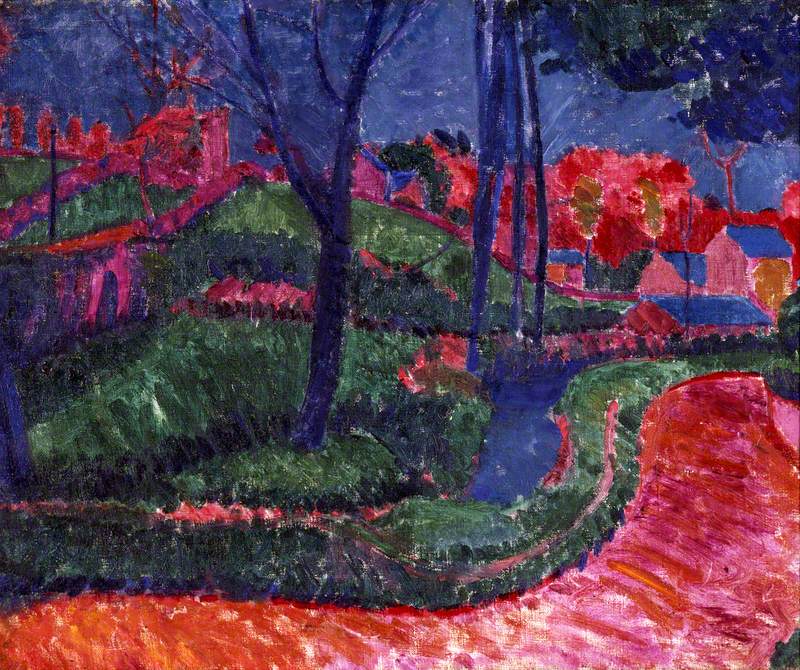

Some twenty years earlier in the summer of 1905 Matisse and Derain had shaken the art world with a series of dazzling images of Collioure which is magnificently sited beneath mountains a few miles from the Spanish border.

Although Ihlee and Mackintosh had a quieter take on the sunlit landscape than those famous 'Fauves', they both produced distinctive work which impresses in contrasting ways.

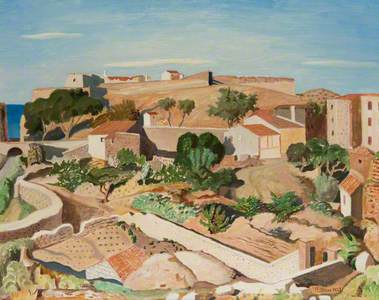

A slow worker, Mackintosh, who was 55 when he moved to France, produced 30 watercolours during his four years of exile. They are as meticulous as the architectural plans which had made his reputation. His palette is cooler than Ihlee's, seldom evoking the characteristic brightness and warmth of the sunbaked landscape. He himself admits to having an 'insane aptitude for seeing green and putting it down here, there and everywhere'.

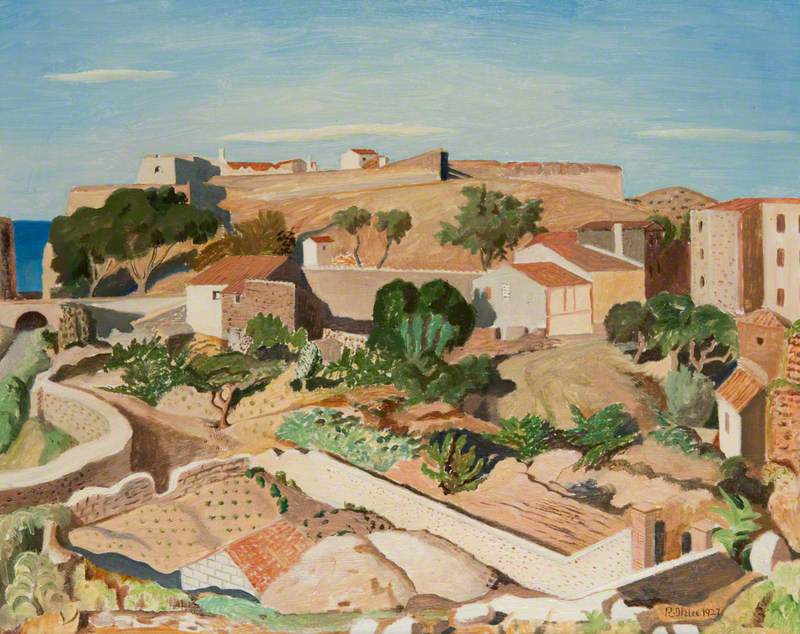

Image credit: The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

A Southern Town

c.1924, watercolour by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928)

Ihlee, who was 15 years younger than Mackintosh, had been a prize-winning student at the Slade where his contemporaries included Stanley Spencer, C. R. W. Nevinson, Mark Gertler and Edward Wadsworth. He was particularly admired for his figure drawing.

Image credit: Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums

Pounding the Bait

1913, sepia pen & ink on paper by Rudolph Ihlee (1883–1968)

Ihlee had two successful solo exhibitions in London before the First World War when pictures, such as The Well, a Breton scene, drew praise from the likes of Walter Sickert and Albert Rutherston.

A qualified engineer, he worked as a draughtsman at a munitions factory in Peterborough until 1918. It was divorce and gradual disillusionment with the London art scene which prompted his exile in 1922.

Accompanied by his lifelong friend Edgar Hereford (1886–1953), the pair had a painting holiday in Algeria before heading to Collioure.

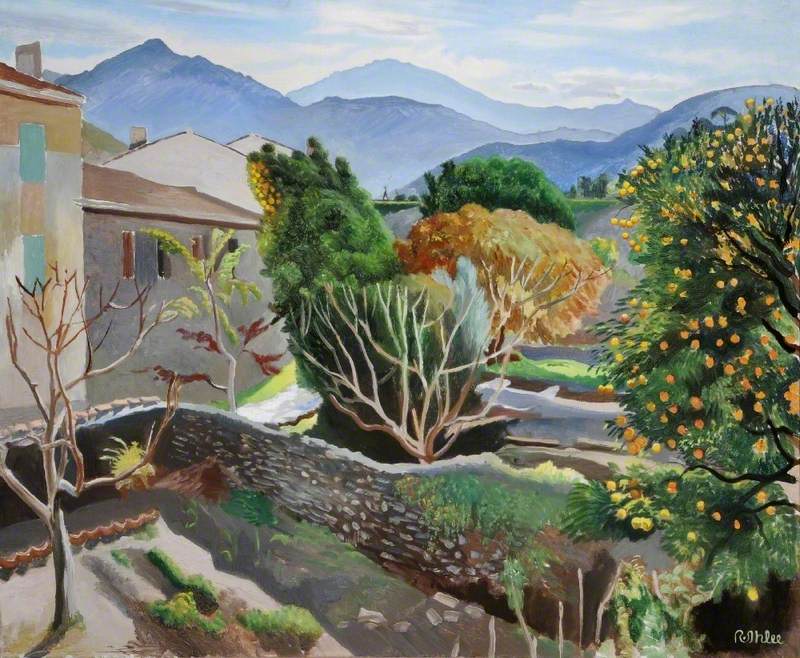

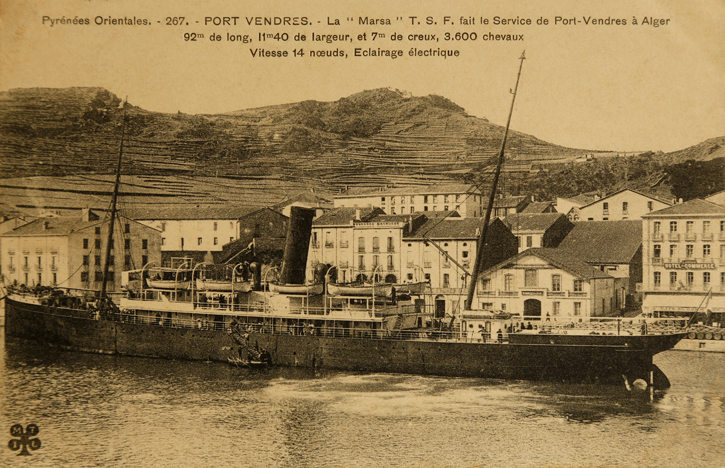

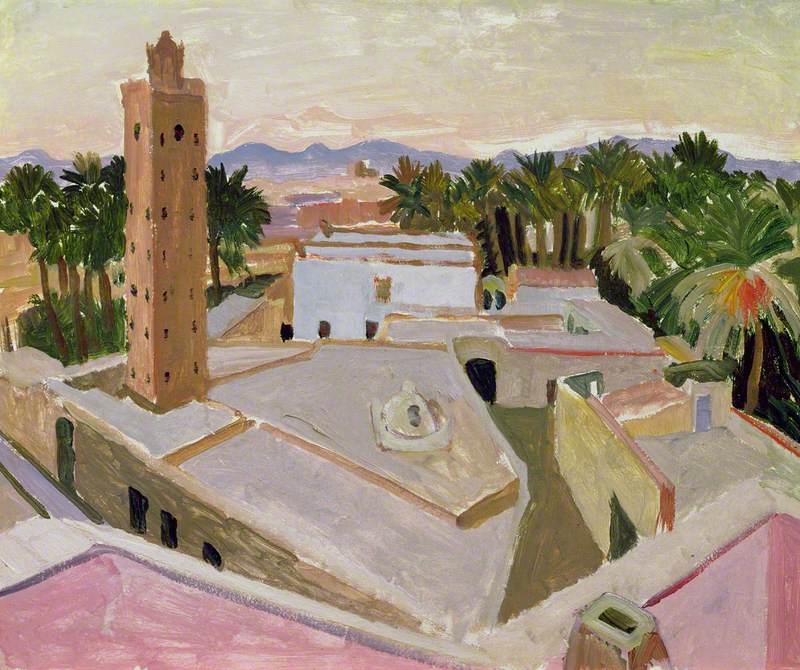

© the copyright holder. Image credit: Courtesy of the Warden and Scholars of New College/Bridgeman Images

North African View (probably the roofs of Tangiers) 1922

Rudolf Ihlee (1883–1968)

New College, University of OxfordThe Mediterranean fishing port brought artistic release. Ihlee's palette became brighter, his brushstrokes bolder and his compositions more fluid as this short film shows.

During his long stay in Collioure, Ihlee produced more than 200 images of the town and surrounding landscape. After a final solo exhibition in London in 1926, he mainly exhibited in Paris and Perpignan although he continued to show with the New English Art Club until his death in 1968.

While Ihlee had a respectable record of sales during nearly two decades in Collioure, Mackintosh sold only two Catalan watercolours in his lifetime.

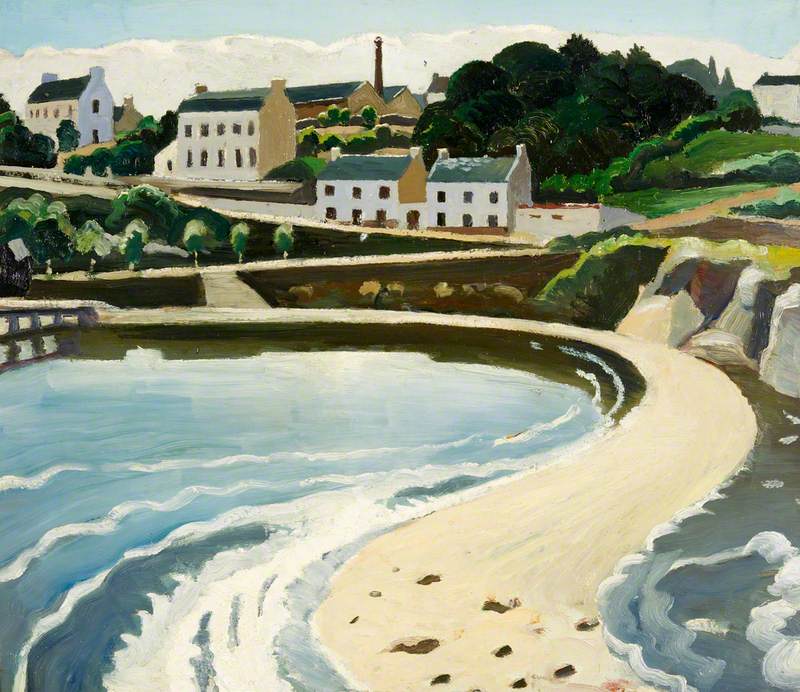

Image credit: The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

La Rue du Soleil, Port Vendres

1926, watercolour by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928)

All may have gone unsold had not his wife Margaret spent six weeks in London in 1927 trying to interest galleries in his work, most of which, according to one of his letters to her, he had neglected to sign:

'I am sorry there were no signatures, I always forget about that, it seems so unimportant but I am sure you can put down my signature on each picture quite easily – do it in pencil and then wet it with clean cold water – you will do it much better than I could have done it.'

The letters he sent to Margaret during her London stay, now in the archive of the Hunterian in Glasgow, give an, at times comic, insight into the lives of the comrades in Catalonia. A keen motorist, Ihlee's car once collided with a cart carrying a load of strawberries between Perpignan to Collioure:

'He had to compensate the driver for the loss and now he has had to take the car to be repaired and to get all the crushed strawberries picked out of every corner of his car. The steering gear and all the machinery was grinding the strawberries into a pulp all the way back to Collioure so it has to be thoroughly overhauled.'

Neither was Mackintosh immune from accidents, one of which involved a painting stool lent to him by Ihlee:

'I had not been sitting on it 5 minutes when down I came, the beautiful leather tore away at one of the nails holding it to one of the wooden legs so there I was sprawling among the cistus.'

While Ihlee became thoroughly integrated into the local community – he met his second wife grape picking and quickly mastered the language – Mackintosh spoke limited French and had fewer Catalan friends. Both men, though, enjoyed a drink and a smoke. They were remembered as frequent visitors to the Hotel des Templiers – a well known Collioure watering hole.

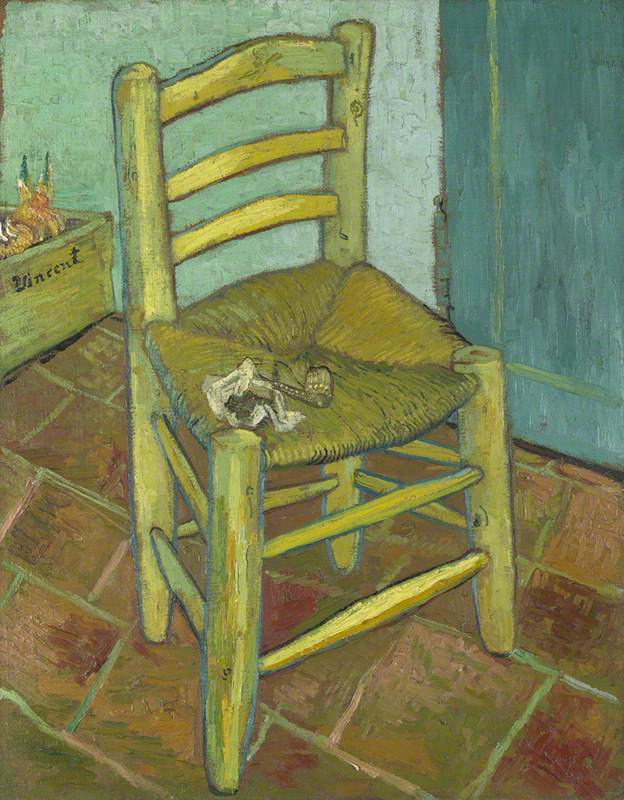

In one letter Mackintosh complained to his wife about a change in the quality of his tobacco which, he thought, caused his tongue to swell. 'Formerly it was light and fragrant now it is sodden, sordid and sickening.'

Sadly, the swelling turned out to be a symptom of a fatal cancer and, when his condition deteriorated it was Ihlee who accompanied him back to London. The younger man is said to have made a last sketch of his friend on the ferry home.

A year later Mackintosh died and Margaret, who outlived him by four years, returned to Catalonia to scatter his ashes.

A hundred years on, Mackintosh's watercolours, which he could hardly give away in his lifetime, can command six figures while Ihlee, who stayed in Collioure until the outbreak of the Second World War, remains relatively unknown which, I hope, my book will remedy.

Image credit: Lund Humphries

Rudolph Ihlee: The Road to Collioure

2002, front cover of book by James Trollope, published by Lund Humphries

In celebration of their friendship, and their Catalan adventure a century ago, both men's work will feature in an exhibition in summer 2022 at the Museum of Modern Art in Collioure.

James Trollope, author and columnist

James's book Rudolph Ihlee: The Road to Collioure is published by Lund Humphries