This year at Art Fund, the national charity for art, we launched The Wild Escape: a nationwide project bringing museums, schools and families together to explore UK wildlife and biodiversity.

We've been working with over 500 museums across the UK to highlight the issue of biodiversity loss by encouraging thousands of children to find animals in their collections and participate in a collective digital artwork, The Wild World.

To help highlight how the UK's museums can be great places to start conversations about the environment and biodiversity, we've selected eight wildlife-themed works of art from UK museum collections. Find out more about them below – and why not use one of them as inspiration for a contribution to The Wild World?

To explore more animals and nature in art, you can also find The Wild Escape on the Bloomberg Connects app.

Find out more on The Wild Escape website.

A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (Anne Lovell?)

about 1526-8

Hans Holbein the younger (c.1497–1543)

Considered one of the greatest artists of the Northern Renaissance, Hans Holbein the younger visited England twice during his lifetime to paint the faces of the Tudor court. Portrait of a Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling was originally thought to picture the adopted daughter of Thomas More, Margaret Giggs; however, in 2004, stained-glass historian David King identified the sitter as Anne Lovell, wife to Francis Lovell, a personal attendant and courtier to Henry VIII.

The presence of both the squirrel and the starling mark her identity: the squirrel is an emblem on the Lovell family's coat of arms, and the starling is likely a pun on the family's hometown, 'East Harling'. Here, the squirrel is perched on the Lady's arms, ravishing on a nut. The metal chain that runs between the critter and the Lady's hand suggests that it is kept as her pet; squirrels were a common domestic companion at the time. The work hung in Houghton Hall, Norfolk, until it was acquired by London's National Gallery with Art Fund support in 1992.

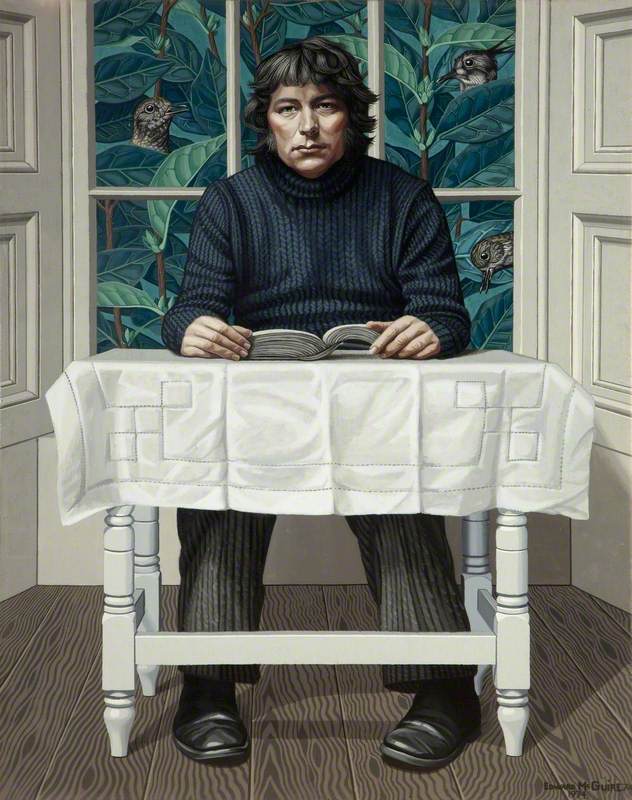

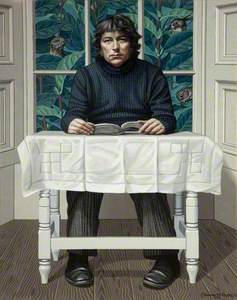

Edward McGuire's instantly recognisable portrait of Seamus Heaney depicts the tousled-haired poet sat in front of a table, donning a navy cable knit jumper with a rolled neck, and grey corduroy trousers. A book is propped on the table, gently held open by hand, but Heaney keeps his gaze forward, his face illuminated, contoured by detailed shadowing, reminiscent of the use of chiaroscuro associated with Renaissance painting.

Beyond the window, overlooking the outdoors, there is a flattening of perspective, giving the image a surreal quality. The green and blue foliage appears to be pressed flat against the window; three birds' heads are peeking out. This subtle backdrop nods to two things: Heaney was celebrated for his poetry of the nature that populated the Ulster landscape, and McGuire was fascinated by the birds he encountered at the Natural History Museum in Dublin, prompting him to start a collection of taxidermy birds and repeatedly paint them throughout his career.

Painted three years before his death, Mark Gertler's painting Fish depicts a glass box filled with two stuffed fish, an image he often returned to. This is one of the earlier renditions of the scene, and is significantly more figurative than the later versions, which are markedly flattened and abstracted. There is no limit to Gertler's use of vibrant colours, which appear throughout the body of the fish, used to create shadow, and in the background in a letterbox-red wall. The bold colours and simplicity of form suggest influences of French and English Post-Impressionism.

Gertler is considered one of the leading figures in early twentieth-century British art. His most famous painting, Merry-Go-Round, offers a commentary on war as figures endlessly go round and round a fairground ride, pointing to his staunch anti-war stance as a pacifist and conscientious objector.

Frog, Mouse and Kite

(artist's proof 22/50) 1970

Edward Bawden

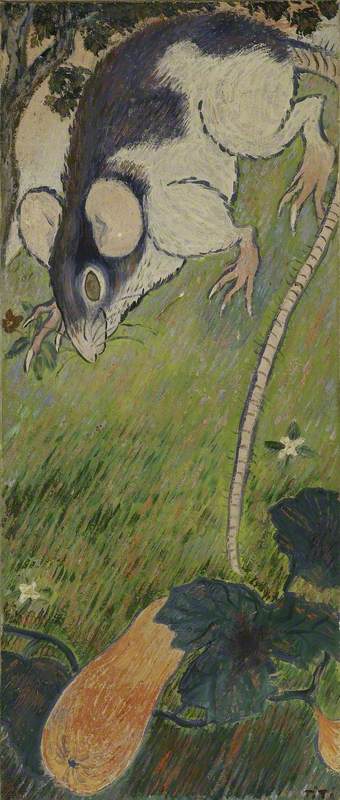

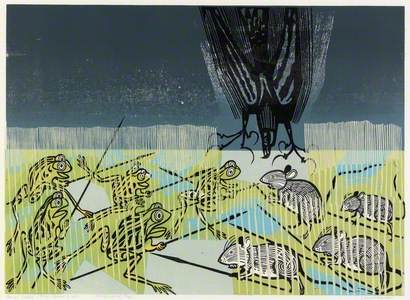

Essex painter and graphic designer Edward Bawden created Frog, Mouse and Kite in 1970 as part of Aesop's Fables, a series of linocuts on paper with each print exploring some of the ancient Greek storyteller's famous tales, including The Hare and the Tortoise. Bawden was taught by celebrated landscape painter and war artist Paul Nash, whose dedication to depicting the British landscape had a lasting influence on the Essex artist.

In this linocut, and in Bawden's style more generally, there is a reduction in detail, common within graphic design, a flattening of form and balancing of line and colour. The frogs and mice are at ground level, with patches of blue and green to represent the habitats they live in. From above, one black kite swoops down from a dark blue sky, its claws stretched out so that it can capture its prey.

One of Edwin Landseer's most famous paintings, due to it becoming an icon of Scotland and a representation of the country's highland culture, The Monarch of the Glen was acquired by National Galleries of Scotland in 2017 with Art Fund support. The painting had originally been commissioned to hang in the House of Lords in the renovated Palace of Westminster following a fire destroying the building; however, on completion it was decided that the government should not be seen to be over-spending on works of art, so it was purchased by a private collector.

The stag is regal; it stands confidently and almost looks across the landscape, evoking a dominance or a sense of national pride. The mountainous landscape in the background subtly shimmers in blues and greys. The overuse of the image in the twentieth century by marketing companies led to it becoming almost clichéd, described as 'the ultimate biscuit tin image'.

Feeding the Pigeons by Jean Young appears to be influenced by Post-Impressionist painting, with its bold application of colours in a pointillist technique creating a kind of dappling effect, most visibly incorporated into the background and the outfits of the two children. There is also a flattening of form, creating an image of two children who are reminiscent of people within a Gauguin painting. Here, they are feeding the pigeons, passing breadcrumbs through the bars of a cage. The pigeons' wings are ornately detailed; each feather is applied with short, thick brushstrokes.

One of the most recognisable images of Surrealism – a movement that emerged following the trauma of the First World War, leading artists to create works that echoed the illogicality and unnerving nature of the state of the world around them – Lobster Telephone by Edward James and Salvador Dalí remains iconic. Combining two everyday images that don't usually coexist, the sculpture exudes both playfulness and threat: picking up this handset might result in a pinch.

Dalí, like many of his fellow Surrealists, was particularly preoccupied with the unconscious, which Sigmund Freud believed emerges when you sleep, when your dream state can concoct disjointed images that often do not make sense during consciousness. Dalí and James made eleven of these phones. Originally designed for James' home, they would function as usable objects.

Inspired by book five of Lucretius' text On the Nature of Things – which explored the start of civilisation and how man overcame his fear of fire and learned how it could be used to make metal – this painting by Italian Renaissance painter Piero di Cosimo places a forest fire at its centre. The rising smoke permeates the skyline, and animals and people are seen fleeing in horror at the scene. Lines of birds flock away in the sky, disappearing into the distant landscapes further afield. It is one of the earlier examples of landscape painting in Renaissance art.

Alex Hull, Editorial Coordinator at Art Fund