Every portrait tells a story of power. Between every sitter and artist, there is a relationship moulded by complex constructs of power. The timeless nature of this relationship, and the power dynamics surrounding it, became the starting point of 'Royals to Ratcatchers'. In September 2021 we (a group of history undergraduates from the University of Southampton) were given the opportunity to curate an exhibition in collaboration with the Southampton City Art Gallery.

When first considering potential themes, several suggestions picked up on the influence of power dynamics (such as gender, class, race, sexuality and age) on the paintings produced, provoking questions surrounding control, identity and ownership. Topical considerations, as social movements (e.g. Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ+ Pride, #MeToo) in recent years have placed renewed focus on identity construction and societal power struggles.

Pulling on this thread of power, we were further inspired by John Berger's famous series Ways of Seeing, in which he discusses the tension that exists between artist, sitter, and viewer within portraiture. Combined, these interests lead to the production of 'Royals to Ratcatchers', exploring the complexity of the power relationships between the people behind and in front of the canvas.

Preparing to hang in Gallery 6

The power of art is in its variety of expression. Subjects can be noble, mysterious, playful, interrogating, sexualised – this spectrum is explored throughout our exhibition. Having settled on our theme, we then worked to establish subsections, requiring consideration of both the thematic and aesthetic qualities of our portraits.

Alderman Sir Sidney Kimber, JP

1939

Thomas Cantrell Dugdale (1880–1952)

We decided on our first subsection: tradition. Those who had the ability to commission their own portraits could decide how they were represented, presenting emblems of their status and legacy. Thomas Cantrell Dugdale depicts Mayor Alderman Kimber displaying his architectural contributions to Southampton, and Cornet Winter relives his past battles under the hand of Joshua Reynolds. The inclusion of such notable artists and sitters as Joshua Reynolds and Edward VII introduces the rich colours and stoic expressions that are characteristic of British portraiture.

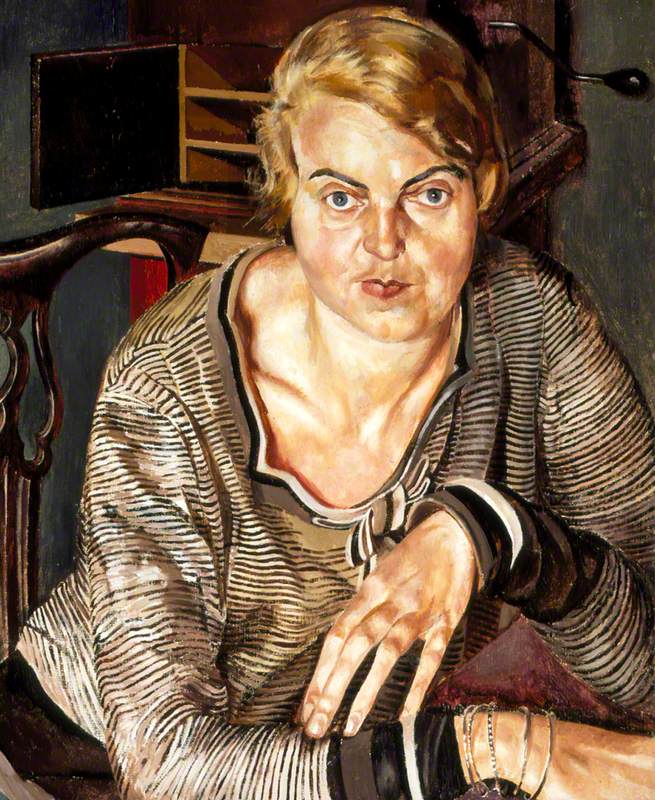

Such archetypal images of authority are then contrasted in the following section: possession. Here, we examine portraits where the portrayal of the sitter is in the hands of the painter. Notably, all paintings in this section conform to the gendered expectations across portraiture of the active male artist and objective female subject.

Hicks portrays the Seated Girl as a figure lacking identity, whereas Patricia Preece is an uncomfortably detailed representation of Stanley Spencer's muse. Despite her marriage to Spencer, Patricia Preece constantly rejected his sexual advances.

Her portrait, where she is presented as harsh and unflattering, is a rare moment for Spencer to have power over the woman he could not control outside of the canvas.

The women depicted in these portraits have possessive relations with their painters, and yet all manage to take on complexities of character not necessarily afforded to them by the artists who observed them. This desired control can be eroded by modern audiences who are able to recognise the power of subjects in spite of their oppressive historical contexts.

After considering power dynamics in relation to gender, we also wanted to examine the significance of labour through our third topic: occupation.

Here, we explore representations of the working class through Gilbert Spencer's (brother of Stanley Spencer) The Rat Catcher and Josef Herman's Miners. Both create sympathetic images of their subjects, but their methods contrast.

While in The Rat Catcher personal details humanise the sitter, the tiredness and collective identity of Herman's miners adds complexity to their monumentality. Interestingly, neither artist paints their subjects at work, focusing instead on the rare periods of rest.

This subsection also included our only self-portrait of the exhibition, William D. Dring's Self Portrait, where artist and sitter become one.

Here, self-definition can be explored as Dring wears his painter's smock over his military uniform, presenting his identity as a war artist but from the comfort of his Southampton studio.

To conclude the exhibition, Anthony Green's The Dinner Party offers a subversion of conventional class power dynamics. Observing from an elevated viewpoint, the viewer looks down upon the outward-looking dinner guests, despite their clear middle-class status, suggesting a more collaborative exchange between sitter, artist, and viewer.

One of the most striking paintings in the exhibition is William Holman Hunt's Afterglow in Egypt which is an example of how power dynamics behind paintings can be complex and challenging.

Hunt uses brilliant colours and fine brushstrokes to create beautiful detail, which, along with the scale of the piece, captivates viewers. The subject of the piece stands tall, her eyes fixed undauntingly on those who look upon her. Understandably, Afterglow in Egypt immediately stood out when scrolling through Southampton's collection on Art UK.

The artwork has, however, proved to be divisive. Some perceive it as a respectful portrayal of an Egyptian peasant while others view it as an accessory to white, middle-class values. Hunt spent time in the Middle East for religious purposes. His decision, therefore, to paint an unveiled Muslim woman seems questionable.

Furthermore, despite extensive writings about his time in Egypt, Hunt fails to mention the name of his model and altered her portrait upon returning England. In doing so, her identity is stripped from her – yet her presence remains commanding. It could be argued that the very fact she was painted at all gives her more power than her peers, who remain anonymous, their identity lost to history.

Thus, Afterglow in Egypt aligned with our intentions for the exhibition: to make the viewers question their own beliefs about what defines power and how the context in which an artwork is created can alter our perception of it. As a result, it was felt among the group to be a must-have in the exhibition and remained a centrepiece in our thoughts when curating the rest.

Selin Moustafa talking to the Mayor of Southampton, Alex Houghton

Curating an exhibition was not something any of us expected we would have the opportunity to do at 19 and 20 years old. Yet, with the guidance of Southampton University lecturer, Dr Jon Conlin, and Assistant Curator at the Southampton City Art Gallery, Tom Laver, the 14 of us had an experience we will never forget. In the early stages, Art UK was with us every step of the way. Our first task was looking through Southampton City Art Gallery's extensive collection on Art UK, in search of potential themes.

Down in the art store beneath Southampton City Art Gallery

Utilising the filter settings on the website, we were able to maintain our focus on British portraiture, helping with what would otherwise have been a daunting task. Once we had decided on our theme, Art UK continued to be vital to its development, enabling us to share potential sub-grouping combinations and identify portraits of particular interest.

We each individually selected a portrait that we felt contributed to the theme and which, when placed alongside others, revealed parallels, and provoked questions of where the power truly lies. The ability to see when the portrait was painted, its size and the medium used, launched our contextual research and ensured we stayed within our broad 200-year timeframe.

Our contextual research was further assisted by access to the City Gallery's archives and use of the on-site public library. The archive was a treasure-chest of information, containing numerous catalogues, books, newspaper cuttings, exhibition leaflets, personal letters, sketches and receipts which, combined with extensive web browsing, provided many of the paintings with a rich backing of primary sources.

For some, exploration into a portrait's past took them further afield, involving contact with the Herman Foundation and descendants of William D. Dring. For other portraits, however, information on the painting and artist was limited.

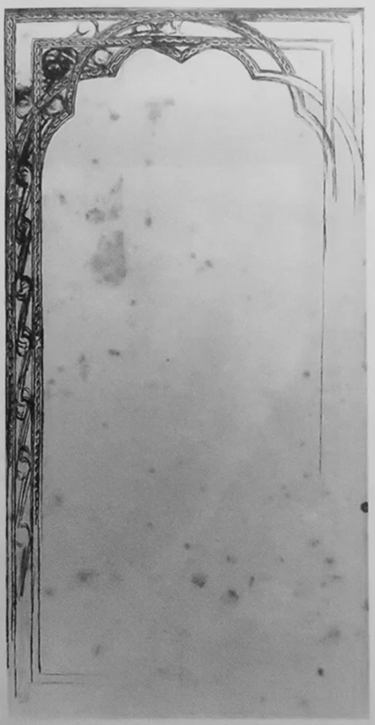

First design for the frame for 'Afterglow in Egypt'

pen & brown ink over pencil by William Holman Hunt (1827–1910)

To divide the workload of a process that usually takes months or years, from concept to realisation, we split into three groups responsible for hanging, labelling and marketing.

The hang team worked alongside Jessica Whitfield (Exhibitions Officer at the Southampton City Art Gallery) to determine the arrangement of the works in the gallery that would best express the narrative of the exhibition and maintain the viewers' engagement. Using the 3D modelling programme Sketch-Up, we were able to mock up potential hangs. This was particularly useful in ensuring the exhibition was in balance and that stronger and physically larger works did not dominate over smaller, more delicate ones.

Final hang mock-up using 3D modelling program Sketch-Up

The label team tackled the sub-section panels which aimed to provide additional insight into our reasoning behind the groupings and an introduction to the particular power dynamic they explored. The major challenge was to distil into just 80 words a thematic interpretation for each painting.

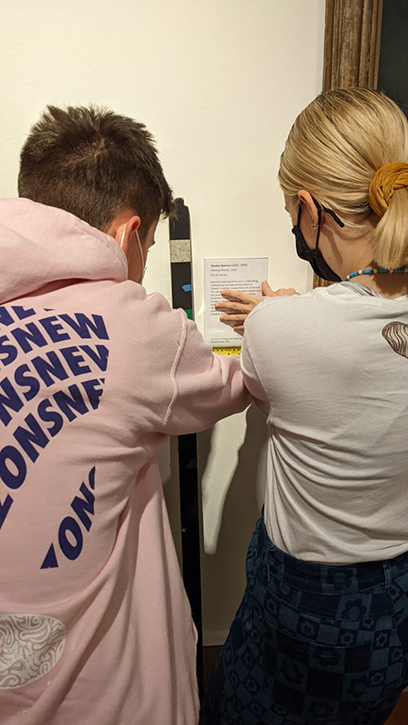

Mike Nichols and Amber White levelling up the label for Stanley Spencer's 'Patricia Preece'

The exhibition announcement and social media posts were generated by the marketing team, with the aim of attracting both new and regular gallery visitors. Across the three groups, we gained an overview of the skills and expertise that combine to create an exhibition.

View this post on Instagram

The experience culminated in the opening of the show on 22nd January 2022. In the week leading up to the opening, we were offered the rare opportunity to see the exhibition installed. We were given access to the art store beneath the gallery and witnessed our chosen paintings being transported up to the gallery floor, finally seeing our chosen portraits in their full-colour glory.

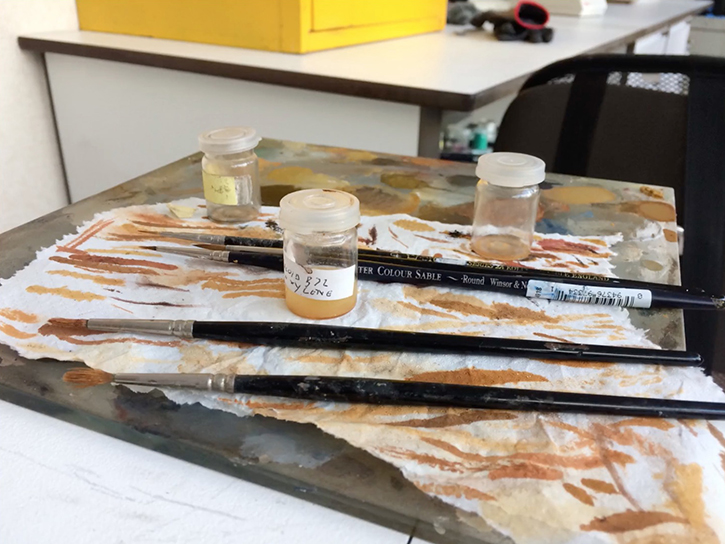

Additionally, some of us visited the conservator's studio which was scattered with paintings in various stages of cleaning, retouching and repairing. We had the chance to experience the exhibition space as it came to life, watching as the portraits – whose faces had become so familiar to us – ascended from their propped-up positions around the room onto their final destination on the walls of Gallery 6.

Conservator's palette used for touching up paint loss on Anthony Green's 'The Dinner Party'

As history students, many of us began the curation journey with a fascination for, but basic understanding of, the art world. Although our understanding of art movements and techniques grew throughout the process, we remained conscious of how the exhibition would appear to the general public who, like us, had varying levels of art historical knowledge. We brought a historical perspective to the project, focusing on the intersection of timeless social structures, such as gender and class, rather than on artistic movements or styles. For us, the context in which the works were created was as important as the composition.

Katie Phillips, Chloë Ward, Selin Moustafa and Bethany O’Dell in discussion

Art is a wonderful tool in the study of society, a tool that we hope to make accessible to all who visit. Following our work on this exhibition, we have been further enlightened to the value of paintings as a historical source and we continue to seek ways to incorporate art into our other wider studies.

Busy Gallery 6 at the official exhibition opening evening – a classy evening of wine and reflection

By exploring how power pervades artwork (both deliberately and accidentally) at a time when identity construction and power dynamics have renewed topical focus, we hope to have challenged the audience's ideas of what power itself is, questioned whether we should define it by social standing, or individual significance, and uncovered the centrality of the relationship between the painter and the painted.

Students (and staff) sat on the fountain outside the Southampton City Art Gallery

Amber White, Hardayn Lall, Tom Laver, Amber Wahlhaus, Dr Jon Conlin, Kristie Nanson, Chloë Ward, Bethany O'Dell and Jaden Beaurain

Chloë Ward, Selin Moustafa, Katie Phillips and Bethany O'Dell, University of Southampton

'Royals to Ratcatchers: 200 years of Power in British Portraiture' is on at the Southampton City Art Gallery until 28th May 2022