While making art from wood has a venerable history in Britain, most contemporary sculptors prefer to use more predictable, longer-lasting substances, such as stone or metal. On the contrary, the British sculptor David Nash finds inspiration in the natural material found all around us, especially in the vagaries of timber in its untreated, unprocessed form.

In homage to Nash's artistic life and observation of trees and wood, 'David Nash: Full Circle' is currently on display at Yorkshire Sculpture Park until 5th June 2022.

Throughout his career, Nash has preferred to use trunks and branches that have fallen naturally or been felled for non-commercial reasons, such as disease. The propensity of the material to expand and change is celebrated in the titles of his works, for example in the piece made by beech: Split Frame: Crack and Warp Square.

Split Frame: Crack and Warp Square

David Nash

Nash's relationship with wood and trees has evolved throughout his career, thanks to close observation and experience. From early on, though, it was clear that ecology and the environment would be fundamental concerns.

Born in Esher, Surrey, Nash studied at Kingston College of Art (1963–1967), after which he moved to Blaenau Ffestiniog, North Wales, initially to escape the UK capital's cost of living. In 1968, he bought Capel Rhiw, a disused chapel, as a studio. Nash returned to London for a year or so to complete his higher diploma at Chelsea School of Art (1969–1970), but then returned to Wales to work with fallen wood from a nearby forest.

He allowed natural imperfections, such as twists and knolls, to remain visible and become intrinsic parts of his work. One of his earliest pieces in a British collection is Split and Held Across, in which willow branches are tied with rope in the manner of some rustic implement of uncertain use.

Before wood is used in sculpture, it is usually seasoned – dried to remove moisture. Leaving the material in its natural state, Nash found that cracks sometimes appeared, so he makes these integral to his work, whether they appear during or after his interventions. These give a particular character to works such as the series that includes Cracking Box, where the imperfections give an unfamiliar feel to what would be an otherwise regular cube.

The box is just one of several geometric forms, alongside pyramids and spheres, that have reappeared throughout his oeuvre, offering varying degrees of dynamism, potential movement and solidity.

Rostrum with Bonks, meanwhile, is one of a series of table-shaped works that followed an exploration into Brancusi-style columns.

The word 'bonks' comes from the nickname given to a rocky outcrop in a field, here referring to a set of rough spheres carved by axe from ash, horse chestnut and birch on their pine base. The ash ball split while drying.

After his first solo exhibition in 1973, Nash began to display works regularly and grew more ambitious, leaving his studio to embark on larger scale land art projects. In 1977 he planted Ash Dome, a group of 22 saplings at a secret location in North Wales that he hoped would grow into a canopy.

Ash Dome

c.1977, circle of 22 ash trees planted by David Nash (b.1945)

During the next year Nash explained he expected to work on it four or five times over four to five decades, 'but then let it go... My own demise will take care of that.'

Ash Dome

2007, drawing with earth on paper by David Nash (b.1945)

However, the trees have since been infected with the disease ash dieback, which probably means he will now outlive them. Also in 1978 he carved a large wooden boulder from a 200-year-old oak tree, which he then rolled into a river in the Welsh mountains. Nash documented its transformation as it moved downstream. Its final siting came in 2003 on a sandbank. As of now, the artist believes it has washed out to sea.

From 1981 to 1982, Nash took on the first of several residencies at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, allowing him to devise pieces that develop with age, either growing or disappearing, shown in two site-specific works that can still be in seen the West Yorkshire setting. Barnsley Lump (1981) comprises a rough cube of locally hewn coal in a field that alludes to the area's geological and social history.

Because it is gradually disintegrating back into the earth, Nash has described it as a 'going work'.

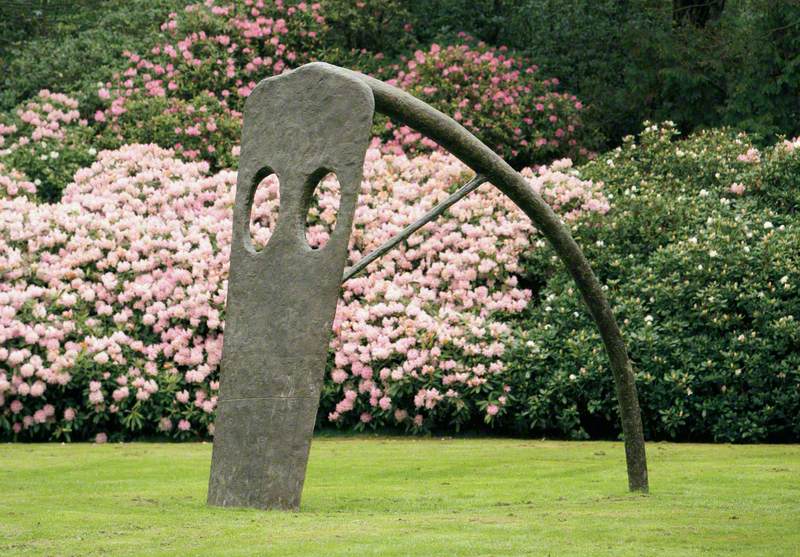

By contrast, Three Stones for Three Trees (1981–1982) is a 'coming work': the artist has planted a sycamore, oak and beech, each next to a large, upright sandstone block, sourced from a local quarry.

As the trees continue to grow, their relationship with the stones evolves.

Nash also became interested in the process of charring wood, inspired by the discovery of centuries-old charcoal burners' sites in Grizedale Forest, Cumbria, while working there as a resident sculptor in 1978. These locations were barely discernible, but their sense of human interaction with nature made a deep impression on the artist.

This has led to a series of works that involved charring wood, whether by passing it through fire or burning with a blowtorch, including commissions for the Forest of Dean Sculpture Trail in Gloucestershire, another area with a history of charcoal manufacture.

Fire and Water Boats (1986) comprises a flotilla of small, charred craft, referencing the oaks planted nearby to supply timber for the Royal Navy.

The transformation of the wood has a marked effect on Nash's relationship with the material, he has explained: 'With wood sculpture one tends to see "wood", a warm familiar material, before reading the form: wood first, form second. Charring radically changes this experience. The surface is transformed from a vegetable to a mineral – carbon – and one sees the form before the material.'

Much of Nash's work continues to gain meaning from particular locations, even when he creates an indoor sculpture rather than outdoors intervention, as is the case with Wafer Throne (1989), devised from a pair of enfolding forms sourced from a single beech that grew in Ashton Court, Bristol, and created on-site. The artist added, 'it is transformation that makes meaning. The objects I make are vessels for the presence of the human being'.

The passage of time continues to be a key theme for Nash, as seen in this series of six columns erected in the National Forest, Leicestershire. Each features a vertical slot through which the sun shines for 10–15 minutes at 'true' noon on midsummer and midwinter days. As well as celebrating the past, present, and future of the forest, The Leicestershire and South Derbyshire Noon Column (2006) marks the region's industrial heritage through its charred facade and surround of crushed coal and brick.

Although known for three-dimensional works, Nash has continued to draw, whether observing nature in detail or recording aspects of ongoing projects. He has also been long fascinated by theories around colour, including how they interact with each other and the spiritual qualities of different tones and how they arouse emotional responses. This side of his creativity is now the focus of an exhibition at Yorkshire Sculpture Park that commemorates an association that has spanned over 40 years, including a major retrospective in 2010.

On show are a series of drawings, all inspired by trees, ranging from documentary sketches to intensely hued works almost abstract in nature. Many are quickly made outdoors, while others such as Red Tree (2021) are worked on in his studio in a more contemplative fashion, often focusing on colour.

Red Tree

2021, drawing by David Nash (b.1945)

All his work, though, reflects what Nash has come to admire from trees, that they 'take just enough and give back more'.

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

'David Nash: Full Circle' runs at Yorkshire Sculpture Park until 5th June 2022

!['Phoebe Boswell: A Tree Says [In These Boughs The World Rustles]' at Orleans House Gallery](https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/w800h800/artuk_stories/boswell753x1000-edited-thumb-1.jpg)