The headstone of Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918) stands in a burial ground in Arras, France. It marks his death on 1st April 1918 aged just 27, though not his body, which could not be identified among a group of soldiers killed while on night patrol. The headstone is engraved with the Star of David, reflective of his Jewish identity. Below it, stand the words 'Artist and Poet'.

Rosenberg's family were forced to pay for the epitaph's inscription, with the Imperial War Graves Commission informing his father Barnett that it was 'unable to accede to your request to engrave the words', but that 'they could be engraved at the foot of the stone as the personal inscription at your expense. The cost of engraving this inscription would be 3/3d.'

This modest act of commemoration identifies the significant and unique legacy that would come to grow around this singular poet-painter.

Rosenberg was born in Bristol in 1890, the son of educated Lithuanian Jews who had fled Tsarist persecution in Russia. In 1897, the family moved to London's East End, where their financial circumstances worsened. Nevertheless, Rosenberg – the eldest of the three sons – was educated at the Baker Street School in Stepney, and took additional drawing lessons at the Arts and Crafts School in Stepney Green. Interested in literature from a young age, a ten-year-old Rosenberg proclaimed to a Whitechapel librarian that he planned to become a poet.

Despite thriving interest and talent, poverty prevented Rosenberg from continuing to art school. Instead, in 1905 at just 14 he became apprenticed to the engraver Carl Hentschel. Though a great admirer of another apprenticed engraver, William Blake ('the highest artist England has ever had'), Rosenberg could find no value in his own work, declaring 'it is horrible to think of all these hours, when my days are full of vigour and my hands and soul craving for self-expression, I am bound, chained to this fiendish mangling machine.'

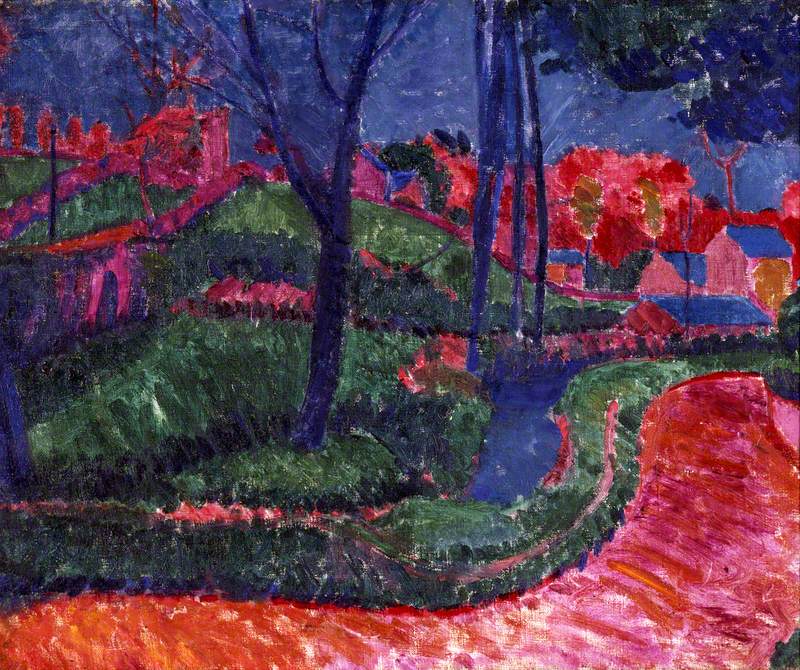

Rosenberg persevered with his artistic training, attending London's Birkbeck College from 1907 to 1908 in his free time, and in 1911 falling in with a dynamic scene of artists and intellectuals centred around the Whitechapel Library and Art Gallery. The 'Whitechapel Boys', as they styled themselves, included fellow East End Jewish artists Mark Gertler and David Bomberg and the poet and later prominent publisher of modernist writing, John Rodker.

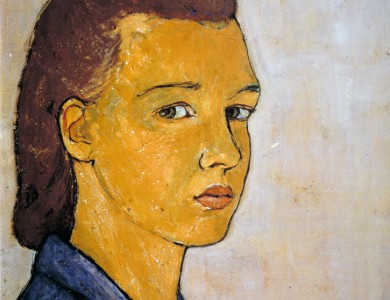

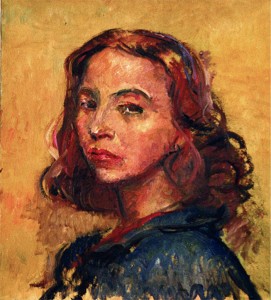

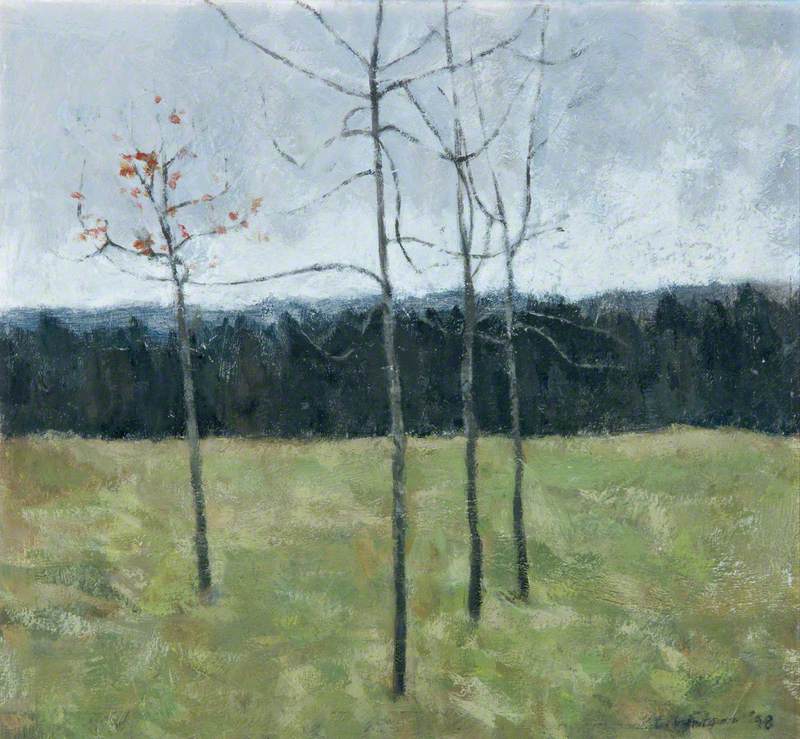

Rosenberg worked on portraits of figures from this world including Clare Winsten (another Whitechapel artist and Slade student) and Sonia Cohen, who would go on to marry Rodker. He also painted a number of landscapes, making visits to Epping Forest and Hampstead Heath to picture a more pastoral scene than the urban world in which he lived and worked.

Yet it was not until a chance encounter with a group of three Jewish women, while he copied Diego Velàzquez's Philip IV of Spain in The National Gallery, that his fortunes began to change. These women agreed to fund the £21 a year Rosenberg required to study at the Slade School of Art, where he would remain until March 1914.

In a remarkable photograph, taken in 1912 at a Slade picnic, a group of young students look back at us. Today, many of them are considered among the most celebrated figures of modern British art. C.R.W. Nevinson and Gertler rub shoulders with Dora Carrington and Edward Wadsworth. Stanley Spencer and Bomberg appear in characteristic attire. Rosenberg kneels, somewhat isolated, to the far left of a group which the tutor Henry Tonks would describe as a 'crisis of brilliance'.

UCL students at The Slade picnic in 1912 @SladeSchool. Extreme left isolated by position & dress is #IsaacRosenberg. One of the most individual voices among poets of the #FirstWorldWar, who was sadly killed on patrol in 1918 #UCLThrowbackThursday https://t.co/GbtyBg2HE8 pic.twitter.com/idGhExiBYf

— UCL (@ucl) May 17, 2018

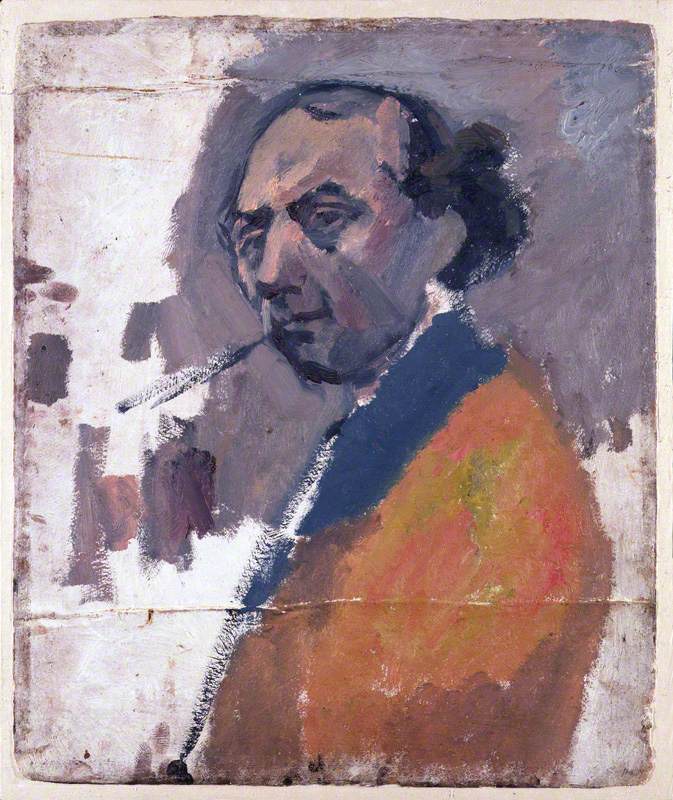

In self-portraits made later in 1914–1915 (a subject choice guided by necessity – models cost money that he did not have), Rosenberg would picture himself in the posture of some of the photograph's more flamboyant figures, donning a 'violently green broad-brimmed Tyrolean' hat.

Rosenberg continued to write poetry, with self-funded collections published in 1912 and 1915, and support coming from well-connected advocates such as Churchill's private secretary and literary patron Edward Marsh and the poet Laurence Binyon. Yet Rosenberg remained something of an outsider. Recommending his poems to the editor of the journal Poetry, Ezra Pound wrote 'I think you may as well give this poor devil a show […] He has something in him, horribly rough but then 'Stepney, East…'

Pound was voicing a snobbery of which Rosenberg was himself acutely conscious. The poverty of his upbringing, he believed, disadvantaged him. 'You mustn't forget the circumstances I have been brought up in, the little education I have had', he wrote in a letter. 'Nobody ever told me what to read, or ever put poetry in my way.'

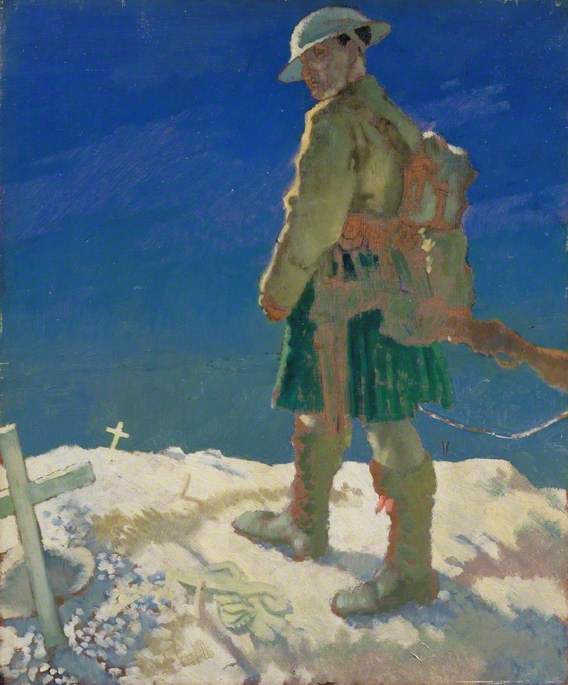

This sense of difference did not diminish with the onset of the First World War, towards which Rosenberg held a natural aversion – an attitude that he assigned hereditary origins: 'my people are Tolstoyans and object to my being in khaki'. But financial pressures forced his hand, and in October 1915 (the same month as Wilfred Owen), Rosenberg enlisted, believing that it would ensure a separation allowance for his mother – money that was not, in the end, forthcoming.

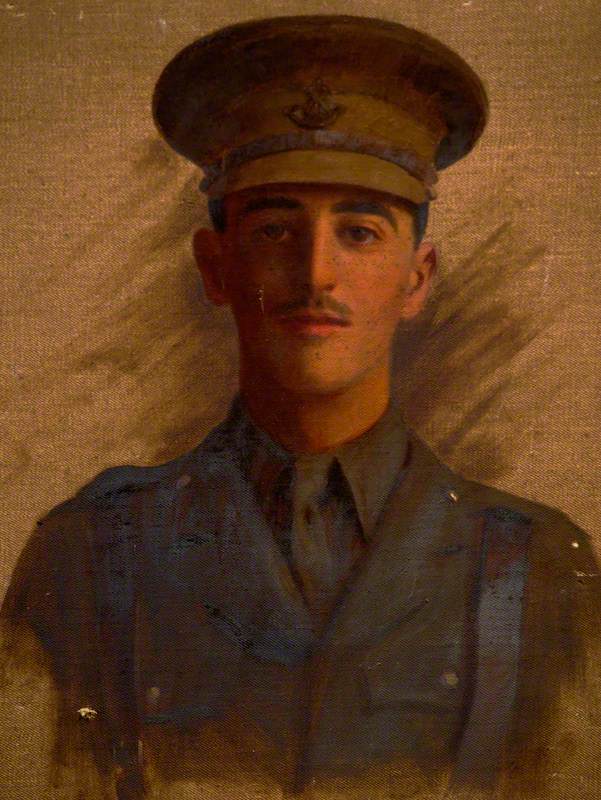

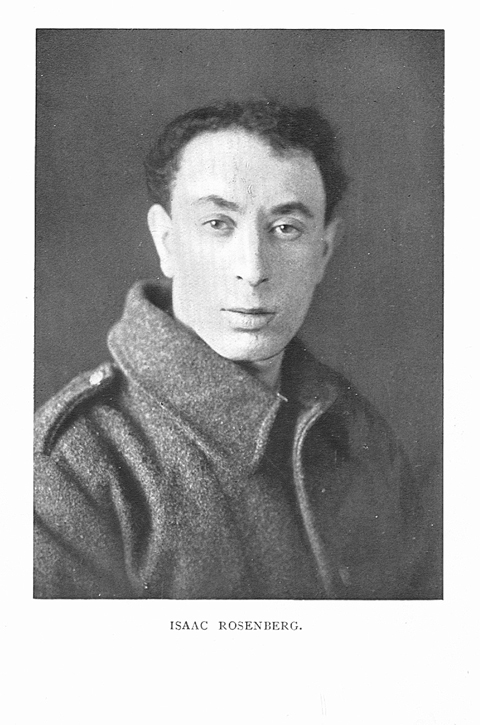

Isaac Rosenberg

photograph published in 'Poems by Isaac Rosenberg' (1922), edited by Gordon Bottomley

Rosenberg found himself enlisted to the Bantam Battalion (units for men standing under five feet three inches). He found them 'a horrible rabble', observing that 'Falstaff's scarecrows were nothing to these'. He was subjected to virulent anti-Semitism, describing how 'my being a Jew makes it bad amongst these wretches.' He put the experience of this prejudice into verse in The Jew, asking 'The blonde, the bronze, the ruddy, / With the same heaving blood, / Keep tide to the moon of Moses. / Then why do they sneer at me?'

It was at the front that Rosenberg became convinced that he was 'more deep and true as a poet than painter' – a fortunate conviction, considering the difficulty of painting while in action, though a number of sketched self-portraits do survive from this period. Instead, scribbling on YMCA-headed notepaper and other scraps, Rosenberg wrote what have become some of the most celebrated poems of the war.

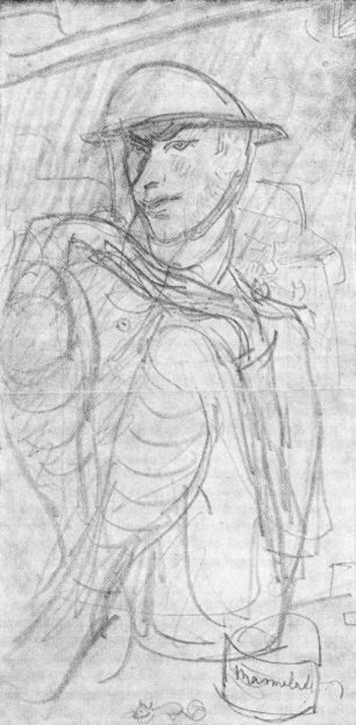

Self-Portrait

1916, sketch by Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918)

Unlike the poetry of officers such as Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon and Edmund Blunden, Rosenberg's verse illuminates the hardships of the lowly private who, writing home, had to 'measure my letter by the light' upon being 'lucky enough to bag an inch of candle.' Indeed, scholars have noted the difficulty of editing Rosenberg's manuscripts, marked as they are with trench mud and water damage: in June 1916 he reported that 'I've been wet through for four days and nights.' He went on, 'the army is the most detestable invention on this earth and nobody but a private in the army knows what it is to be a slave.'

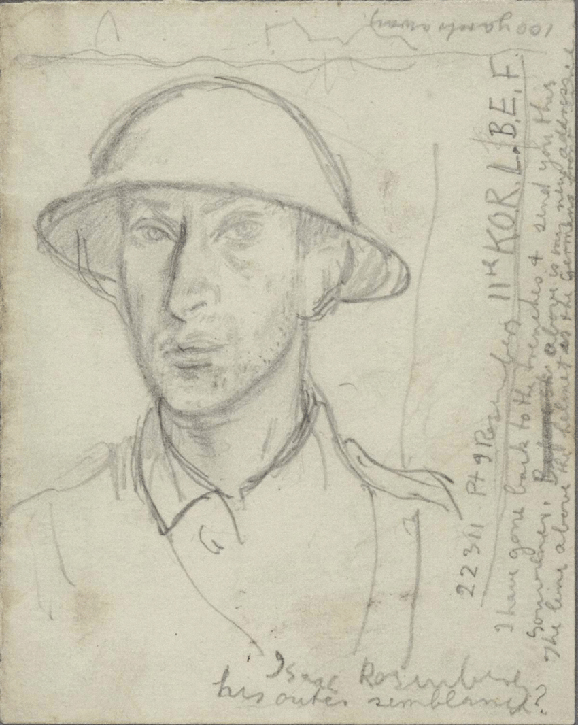

Self-Portrait

1916, sketch by Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918)

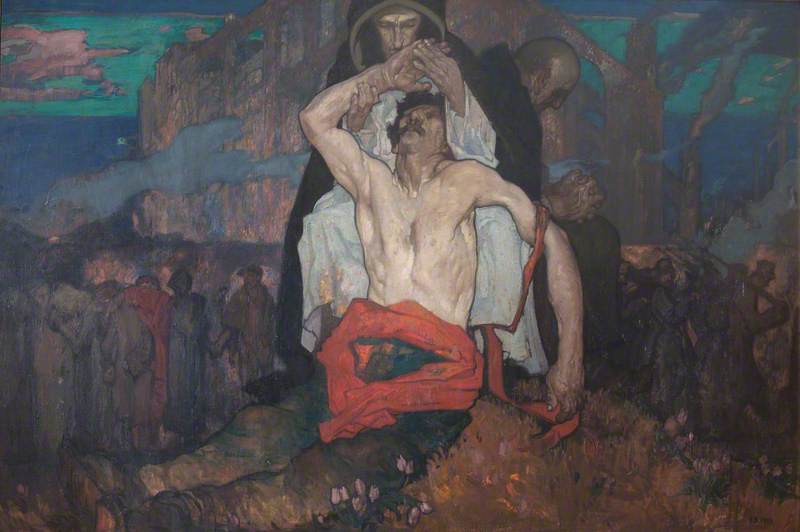

In spite of such hardship, Rosenberg was determined that 'this war, with all its powers for devastation, shall not master my poeting.' He would 'not leave a corner of my consciousness covered up, but saturate myself with the strange and extraordinary new conditions of this life […] it will all refine itself into poetry later on.'

The strange and extraordinary conditions of trench warfare were expressed in verse which told unsparingly of its horror. For Sassoon, writing a foreword to a posthumous collection of Rosenberg's poetry, 'Sensuous front-line existence is there, hateful and repellent, unforgettable and inescapable.'

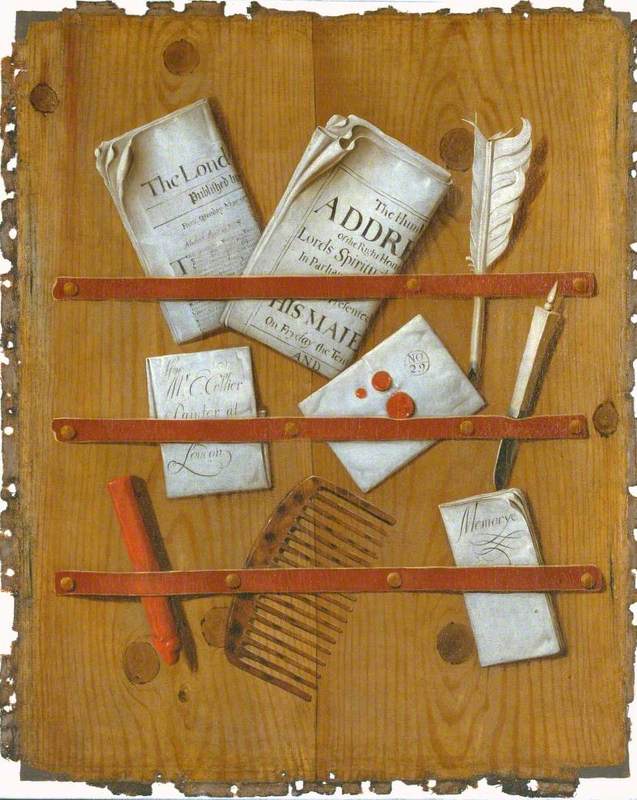

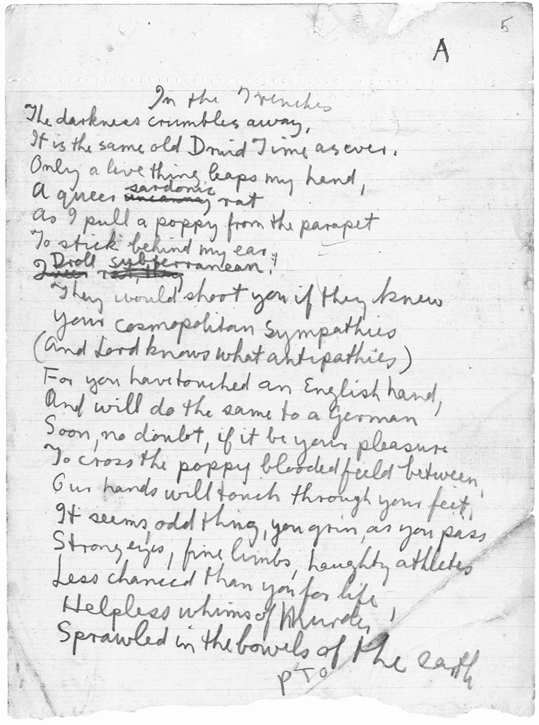

Break of Day in the Trenches

1917, poem by Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918)

One of Rosenberg's most celebrated poems, Break of Day in the Trenches centres upon the figure of the rat so despised by men who were forced to live among them. Yet it is through this reviled creature that the senselessness of war is illuminated and the arbitrary nature of national enmity revealed: 'Now you have touched this English hand / You will do the same to a German / Soon, no doubt, if it be your pleasure / To cross the sleeping green between.'

Appreciation was slow to arrive: in 1922, Edith Sitwell remarked that 'Isaac Rosenberg is one of the greatest poets we have had in this or the last generation, and I do not understand why the critics are preserving this strange silence on the subject.'

Self-Portrait in Army Steel Helmet

1916, black chalk, gouache & wash on paper by Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918)

In the century since, Rosenberg has come to be regarded as one of the greatest British poets of the First World War. In a self-portrait made on brown paper during the Somme offensive, he looks with defiance towards the viewer, his eyes seeming to communicate the poignant words found among his papers: 'Death does not conquer me, I conquer death, I am the master.'

Chloe Nahum, PhD candidate at the University of Oxford

Further reading

Jean Liddiard, The Half-Used Life, Gollancz, 1975

Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Isaac Rosenberg: Poet and Painter, Cecil Woolf, 1975

Vivien Noakes, The Poetry and Plays of Isaac Rosenberg, Oxford University Press, 2004

Ian Parsons (ed.), The Collected Works of Isaac Rosenberg, Chatto & Windus, 1984

Santanu Das, Touch and Intimacy in First World War Literature, 2005