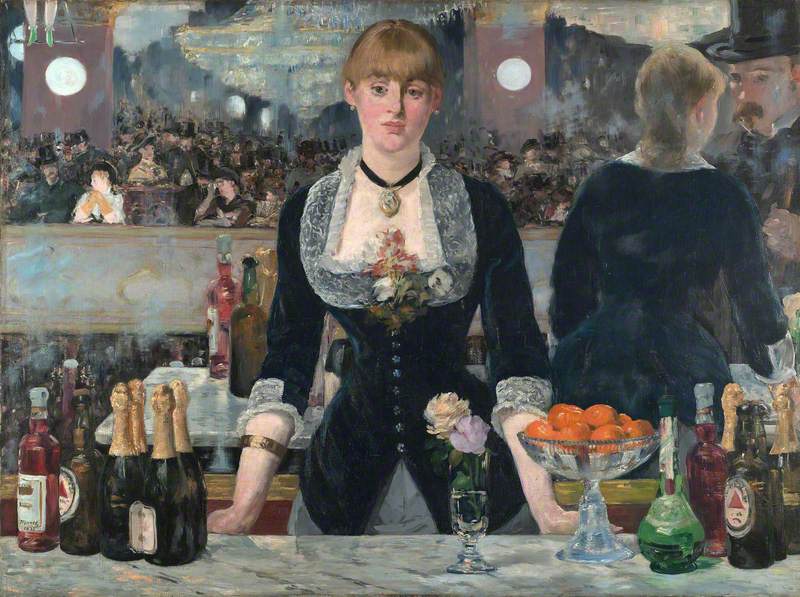

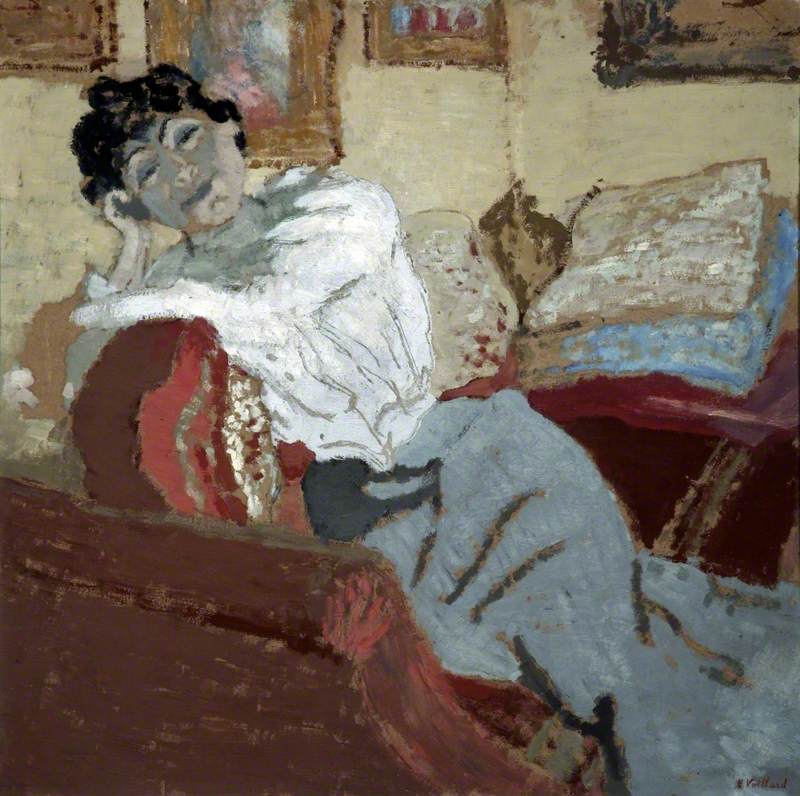

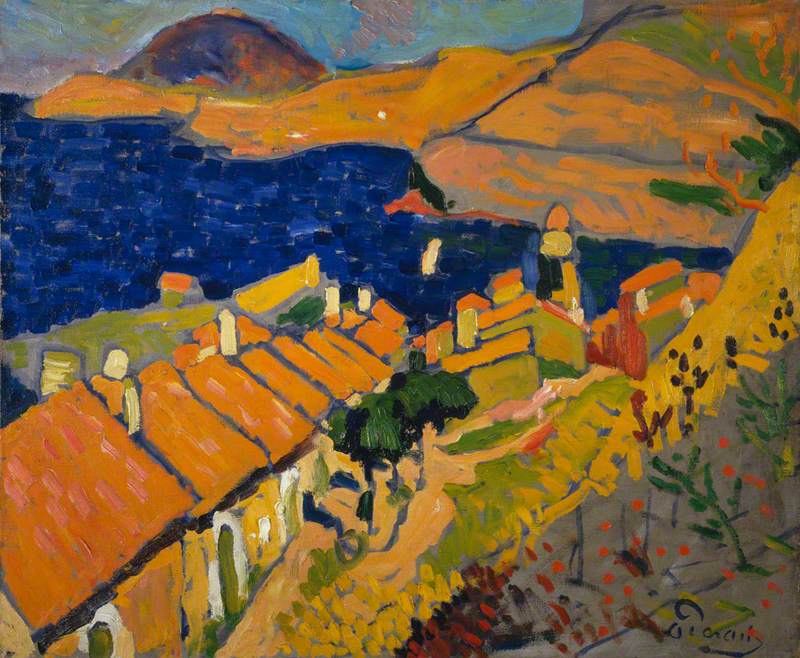

In works by Matisse, Manet, Chagall, Renoir, Degas, Léger and Picasso, the Ashmolean exhibition 'Degas to Picasso: Creating Modernism in France' tells one of the most compelling stories in the history of art – the rise of Modernism. It celebrates over 150 years of art produced in Paris, where international artists and collectors were drawn by salons, dealers, creative exchange, and the bohemian atmosphere.

#DegasToPicasso opens 10 Feb. Explore the rise of Modernism in France through works by Matisse, Manet, Chagall, Renoir, Degas, Picasso +more pic.twitter.com/s0ucOvtDqG

— Ashmolean Museum (@AshmoleanMuseum) February 2, 2017

The forms that progressive art took in that time are wonderfully diverse, focusing on new 'modern' subjects, and challenging formal assumptions about how to represent human experience in two dimensions. At the same time, more traditional approaches to art associated with the French Academy continued to provide a productive counterpoint to the experiments of the avant-garde.

With over 100 works by 43 artists on loan from a private collection which has never before been seen in Britain, this is a unique opportunity to discover paintings, drawings and prints by artists who became famous in their lifetime as well as those innovators who are not represented in UK collections.

The exhibition takes the French Revolution as its starting point: during this time, portrait drawings were becoming increasingly popular, as they were more affordable and so there was a growing market for them.

Portrait of Francois Gerard

c.1789/1790, black crayon & stump on paper by Jean-Baptiste Isabey (1767–1855). Private collection

Isabey was successful as a painter of miniatures and principal painter at the Napoleonic court. Isabey's particular style with its slightly soft focus was based on English mezzotints which were popular at the time.

The successive political upheavals of the first half of the nineteenth century, which included two further revolutions in 1830 and 1848, encouraged a spirit of rebellion in the arts. Satire flourished in the illustrated press and specific artistic styles were readily associated with particular political positions. Millet's un-idealised depictions of nature and rural life, for instance, were read by some as challenges to the modern and increasingly urban-centred French State.

The Seaweed Gatherers

1854, charcoal & white bodycolour on buff paper by Jean-François Millet (1814–1875). Private collection

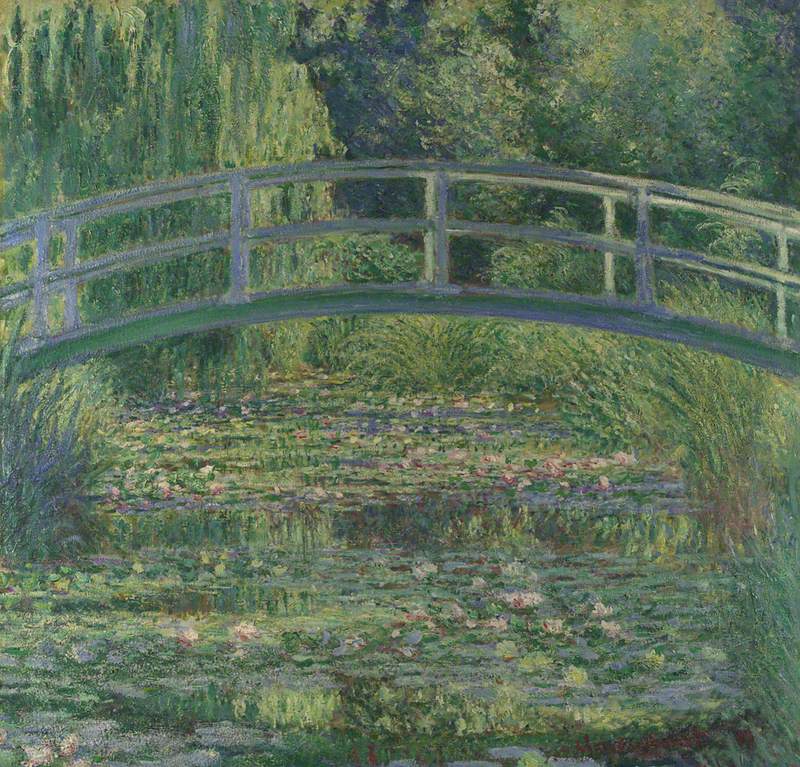

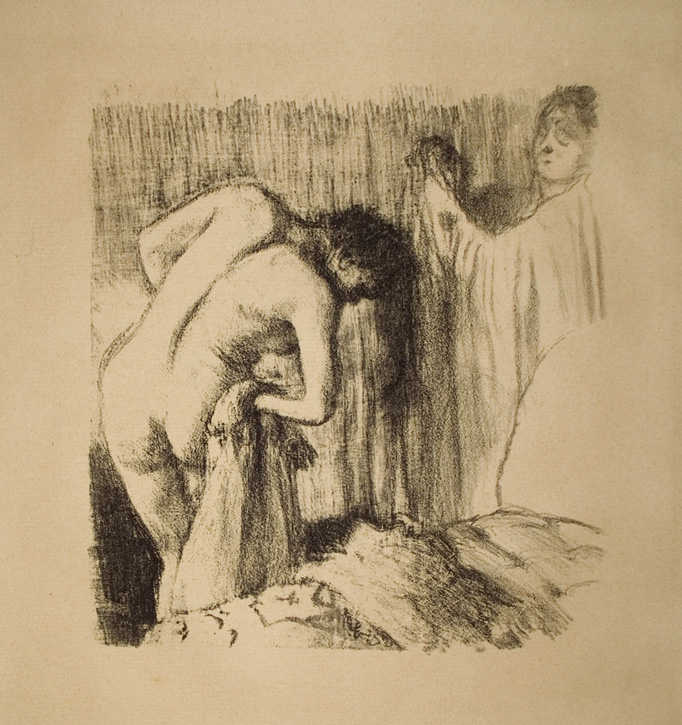

Unable to show their work at the French Academy's annual exhibition, the 'Salon', Degas, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and Cézanne joined forces to organise their own independent exhibition in 1874, the first Impressionist exhibition. From 1887 Degas made a series of drawings of a woman drying her foot while seated on the edge of a bathtub. Here the tub is not drawn, making the crouching pose appear somewhat awkward.

Woman after her Bath

c.1900/1905, charcoal & green pastel on buff paper by Edgar Degas (1834–1917). Private collection

After the Bath, Woman Drying her Leg

c.1900/1905, charcoal, white chalk & pastel on tracing paper by Edgar Degas (1834–1917). Private collection

The Impressionist exhibitions were among the first of many organised by groups who turned their backs on the Salon. These artists became known generically as 'independents' and by 1884 there was even an art review and an exhibiting society of the same name. This was the exciting environment that foreign artists found on their arrival in the French capital at the turn of the century.

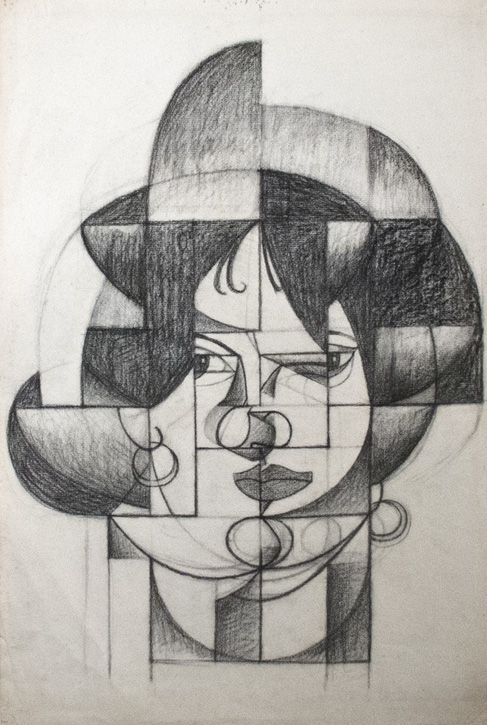

By 1910, Braque and Picasso had developed their form of Cubism, which had a growing band of followers including Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Auguste Herbin and Fernand Léger.

In October 1912 the largest and most important showing of Cubism in Paris was staged at the so-called 'Salon de la Section d'Or'. The Salon included around 200 Cubist works as well as the first ever abstract painting shown in Paris (by Frantisek Kupka). A number of works from the exhibition were sent to New York where in 1913 they featured in a monumental display of progressive European art (the Armory Show).

Head of Germaine Raynal

1912, charcoal on paper by Juan Gris (1887–1927). Private collection

Villon's 1912 composition Soldiers Marching conveys a strong dynamism, usually absent from Picasso's or Braque's early Cubism, and a willingness to apply Cubist principles to a broader range of subjects.

Léger's bold, abstract 1913 Contrasts of Forms was intended to evoke both sound and movement. The works in the series all use simple geometric shapes and bright primary colours to suggest machine-like objects in motion. An abstract, machine aesthetic became a cornerstone of twentieth-century Modernism.

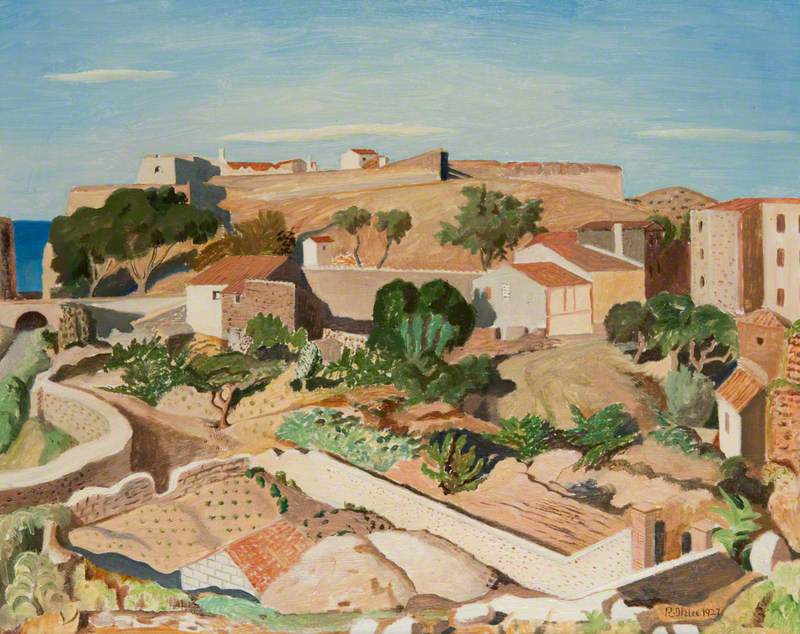

After the First World War, art in Paris continued to set the agenda for Modernism worldwide. Cubism, in all its diversity, continued to flourish and feed into the mainstream design aesthetic of the Jazz Age. But the effects of the War also persisted, not only in work haunted by the conflict, but in a politicised interest in the lives of ordinary people.

Looking at Study for 'Three Musicians' (also known as 'Le guéridon blanc'), a 1920 gouache on paper by Pablo Picasso, with flat areas of bright colour and fragmented shapes, juxtaposed like paper cut-outs, derive from Synthetic Cubism, but are clearer and simpler than they would have been in Picasso's earlier Cubist compositions. The painting is also thought by some to have possibly been a tribute to Picasso's friend Apollinaire, who had died in 1918.

Thanks @AshmoleanMuseum for our sneak peek of #DegasToPicasso. This wonderful exhibition is now open, 50% off entry with #NationalArtPass pic.twitter.com/1Rw590Cd4v

— Art Fund (@artfund) February 10, 2017

Alongside ongoing innovation, artists in France looked back to consider their place within the history of art. When France was occupied during the Second World War, some artists turned to even older national traditions for inspiration. By the end of the War, Matisse and Picasso had themselves become French institutions and from then on, their place within the grand tradition of French art became incontestable.

Picasso had been drawing in a linear style ever since his return to classicism during the 1920s. From the 1950s onwards (e.g. see Bathers, 1961, graphite on wove paper), he also began to revisit earlier masterpieces of modern art, such as Delacroix's Women of Algiers and Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe. In hundreds of rapidly executed line drawings, Picasso extemporised on the themes that had appeared in his predecessors' works.

Agnes Valenčak, Head of Exhibitions at the Ashmolean Museum

'Degas to Picasso: Creating Modernism in France' was on display from 10th February to 7th May 2017 at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford